How to avoid conflict of interest in resolving election stalemate

Two major political parties of Bangladesh are on a collision course. The opposition demands the next general election to help under an impartial, caretaker government. The ruling party is staunchly against that. It is not hard to guess that next year will likely be a time of political unrest, social instability and turmoil. This is undesirable when the country just came out of a pandemic and the world is heading towards an economic downturn.

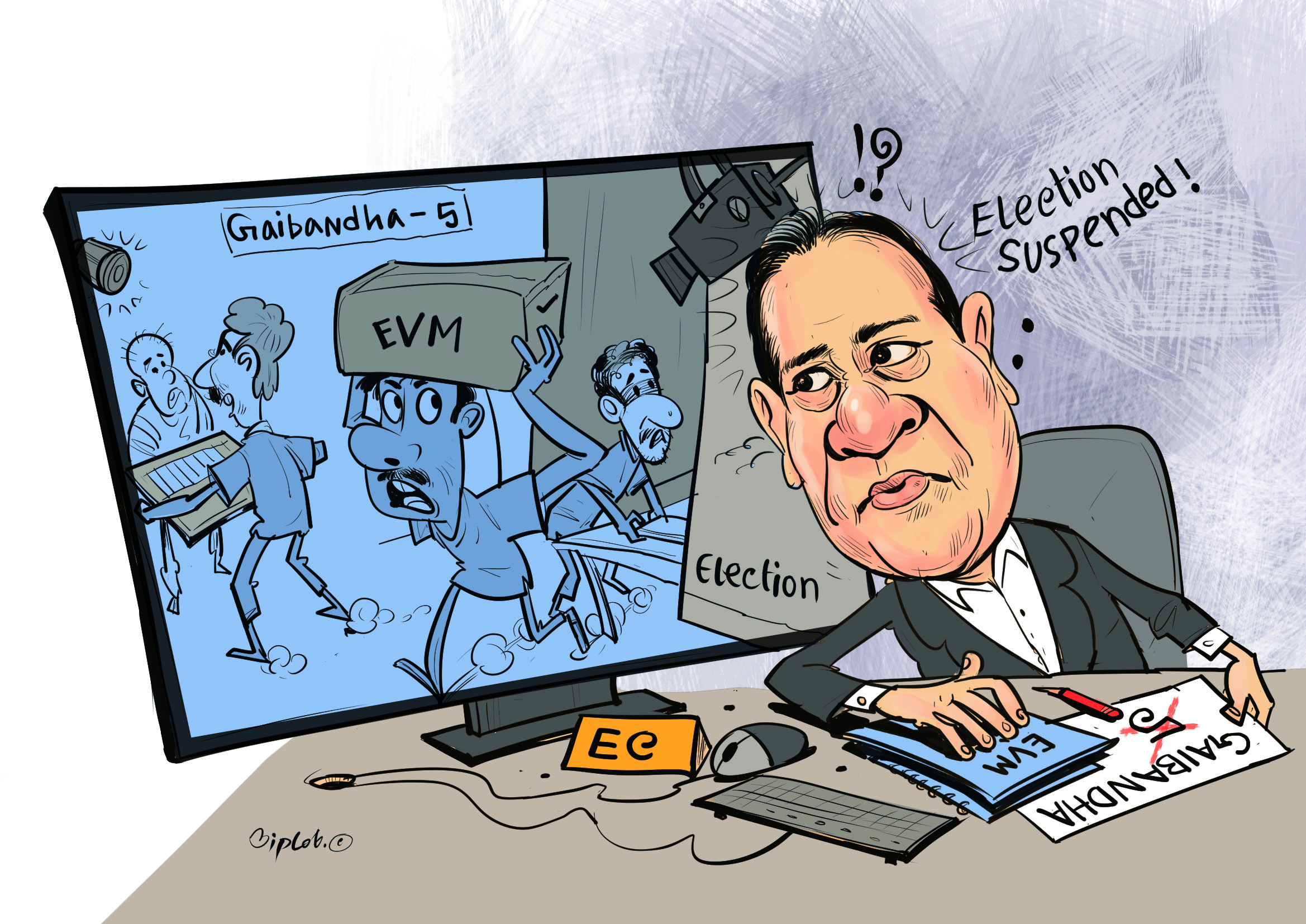

I had the opportunity to be a part of the Bangladesh Civil Service (administration) for some time and was involved with election duties in many capacities. Voting can be manipulated through many tactics. The common scenarios include polling centres being overrun by political musclemen, vote-counting being influenced at presiding or returning officer's level, law enforcement officials taking over the control of polling centres allowing ballot-stuffing, etc. All these can happen either by direct patronisation of the administration or because of their blindness.

Under an incumbent government, the Election Commission may not be able to exercise their full control over the field administration for various reasons, but the most important is the "conflict of interest." This occurs when an individual's personal interests compromise his or her judgement, decisions or actions. A conflict of interest, since it blurs the normal judgement, must be taken very seriously while assigning important responsibilities. Deputy commissioners (DCs) and superintendents of police (SPs) – two main facilitators of an election – become so perniciously politicalised during normal times and benefit from the ruling regime that they find it essential for their own sakes to keep the status quo. Under such a situation, assigning them with election-related responsibilities creates a strong conflict of interest.

An election process broadly consists of: (1) administering the voting and vote-counting process; and (2) maintenance of law and order. Election commissioners are tenured for five years with high status and handsome remuneration. This can provide a strong temptation for anyone to remain in that position for as long as possible, by any means. A long period also exposes the election commissioners to the risk of being politicised.

To resolve such conflicts of interest, similar to the appointment of returning officers, election commissioners can also be engaged for a very brief period to conduct an election. Such individuals can be selected from retired people who have either never worked for the state or from those who left government service long before an election. Duties such as hearing election-related complaints and appeals can be outsourced to retired judges on an "appointed when required" basis. Returning officers should also be appointed from the pool of retired people – one for each constituency. There is a proposal that returning officers can be permanent officers of the Election Commission, but this will only shift the problem. As long as returning officers are being paid by the state and dependent on paycheques for subsistence, they would remain under similar conflict of interest. Presiding officers may be sourced from private and government officials, as they are currently being appointed, but they must not be posted in their place of residence or work for election duties.

The members of Bangladesh Police work under high political exposure in their normal course of profession. This makes it difficult for them to act neutrally during elections. Solutions may include involving armed forces. For better supervision and to deploy forces with greater concentration, elections can be conducted in several days instead of one day. Battery-powered mobile CCTV cameras can be installed inside polling centres so that returning officers can monitor voting from control rooms.

In conclusion, I would like to emphasise that the root cause lies within the state and its different wings – legislative, judicial, and the executive. Complete overhaul of the past colonial system was necessary just after independence from the British Raj, but that never happened. People were kept unaware of the actual state of affairs for the perpetuity of the same class of leaders who had been in power since the days of Permanent Settlement. Maulana Bhashani said that very precisely, "If the peasants and working class are kept unaware of the system then it is easy to exploit – (but) if they become conscious of their rights, then tyrant regimes along with their flatterers are bound to collapse." The permanent solution of a free and fair election is to make the masses aware of the importance of their votes and voting.

Saifur Rahman is a senior IT specialist working in the Australian Public Service.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments