Abul Mansur’s lament was the unfulfilled promise of democracy

Following the July uprising that led to the fall of autocracy, discussions on three key issues—the constitution, elections, and democracy—have gained new momentum. This is because the existing constitution has been abused at will by autocratic rulers to legitimise their authority. Amid these debates, the demand for constitutional reform, driven by aspirations for democracy, has emerged as the most prominent topic.

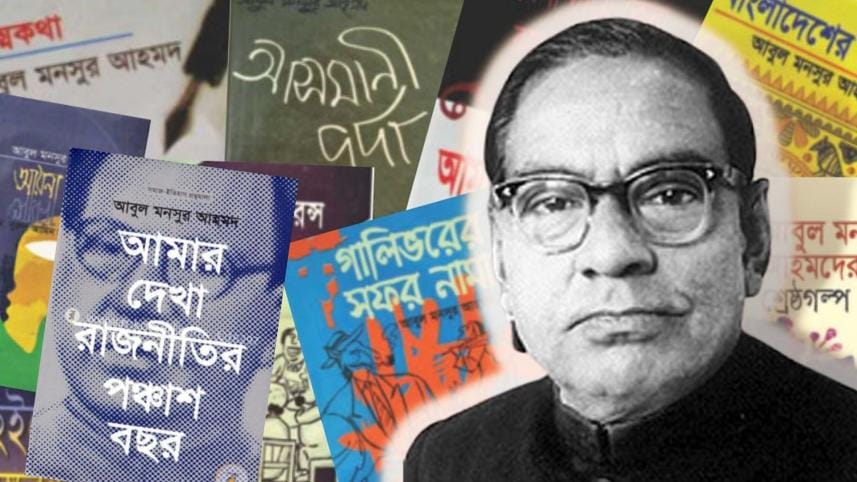

In this context, the thoughts of renowned writer and political thinker Abul Mansur Ahmad have resurfaced. He is one of the primary Bangalee Muslim middle-class intellectuals who documented history through the lens of politics. His widely read book, Amar Dekha Rajnitir Ponchash Bochor (Fifty Years of Politics as I Saw It), offers insights into many issues concerning the constitution, elections, and democracy in Bangladesh. These issues remain unresolved even after 54 years and keep resurfacing in the political discourse. Meanwhile, ordinary people continue to shed blood in pursuit of an egalitarian society.

After the 1972 constitution was drafted, Abul Mansur Ahmad raised a profound argument regarding "legislative error in the Constitution." He wrote: "Democracy, socialism, nationalism, and secularism have been established as the fundamental principles of our state. I strongly support all four. However, in my opinion, none of them, except for democracy, should have been mentioned in the constitution as fundamental principles. Except for democracy, the rest are government policies, not state policies. If democracy is properly established, all other noble objectives will naturally be achieved. Nationalism, socialism, and secularism all serve the people; therefore, they benefit a democratic state. But absolute democracy is the only true guarantee of well-being. If democracy is not secured, none of the other principles will be either."

This has indeed been the reality. The lack of democratic practice has forced us to face multifaceted crises—including authoritarian rule within political parties, one-party governance, periods of military dictatorship, and the concentration of power in the hands of a single political force. The constitution has been amended to serve vested interests. Elections became questionable, and the integrity of the constitution has been repeatedly compromised, leaving the nation's democratic aspirations frustrated year after year. And yet, no one seems to care!

Political leaders have misled the people with empty promises since independence. Abul Mansur Ahmad captured this harsh truth in his writings. He observed that although the Awami League secured an overwhelming majority in the 1973 general elections, polls in several constituencies faced allegations of irregularities. He noted:

"Even if there were around twenty-five opposition members in a 315-member parliament, it would not have harmed the ruling party in any way. On the contrary, having parliamentarians in the opposition would have enhanced the elegance and vitality of the parliament… Bangladesh's parliament could have evolved into a training college for parliamentary democracy. And all the credit for this positive outcome would have gone to Sheikh Mujib."

The leader who once inspired mass hope ended up causing disappointment. Parliamentary elections are a fundamental component of democratic practice, and even that process was undermined. They forgot that democracy is not just a constitutional principle—it must be actively practiced. Abul Mansur Ahmad made this abundantly clear:

"Elections are the political school for the people. Leaders and candidates are the teachers at this school. They must not misguide the students instead of giving them a good education. They should not attempt to explain what they do not understand. They must not ask the people to believe in something they do not believe in. If they do, not only the students but also the teachers will suffer the consequences."

This was the beginning of our downfall. Instead of cultivating good governance, leaders have continuously engaged in the politics of crisis. Yet, whenever necessary, Abul Mansur Ahmad fearlessly spoke the truth—be it in Pakistan or independent Bangladesh. This reminds me of columnist Syed Abul Maksud, who wrote nearly 15 years ago: "The unfortunate people of this country have been learning lessons on democracy from various so-called masters and gurus for nearly three-quarters of a century. They continue to study but never pass. Like Adu bhai, they remain stuck in the same class. However, the key difference between students in a traditional school or madrasa and Bangladesh's students of democracy is that it is the students who fail or pass in conventional education, but in the case of democracy, it is the teachers who are failing more than the students."—Prothom Alo, September 2, 2010

In the writings of Abul Mansur Ahmad, we see examples of Sheikh Mujib's shortcomings. His writings present many such historical accounts. This book can be considered an extraordinary document covering the period from the 1920s to the 1970s.

Like many of his contemporaries, Abul Mansur Ahmad began his political journey by participating in the Krishak-Praja conference. Later, he and many others became involved in Muslim League politics. However, the Pakistan they had envisioned never materialised. It did not take long for the Bangalee middle class to become disillusioned. Once again, the cycle of struggle and resistance, and a political narrative of gains and losses began. But Abul Mansur Ahmad did not remain silent. He spoke out, wrote extensively, and took action whenever possible—sometimes as a lawyer, sometimes as a writer or journalist, and at times, as a politician.

As a guardian of political thought, he warned against the misuse of religion in politics. Yet, even today, religion continues to be exploited recklessly.

In a chapter titled "Dhormo Shashito Rashtro, Na Rashtro Shashito Dhormo" (Religion-Governed State or State-Governed Religion) from his book Beshi Dame Kena, Kom Dame Becha Amader Swadhinota, he expressed a harsh but undeniable truth: "Those who have sought to govern the state through religion, in the end, subjected religion to the control of the state. A religion-governed state would have been ideal if it were possible. But history teaches us that it is not. Those who ignore this lesson and attempt to mix religion with politics, end up harming both. And the damage to religion is far worse for people than the damage to the state. Yet, they remain unaware of the harm they are inflicting on religion."

Abul Mansur Ahmad fearlessly articulated many such harsh truths in various contexts. There is no inherent contradiction between the 1972 constitution and the ideals of the Liberation War in addressing social inequalities. However, their implementation has been inadequate, leading to widespread deprivation. The constitution promised equality before the law, but that promise has remained unfulfilled.

And because that promise was not fulfilled, Bangladesh's youth led an unprecedented mass uprising on July 36. Such a wave of resistance had never been seen before in the monsoon. It was reminiscent of Kazi Nazrul Islam's poetic vision of rebellion. Such revolutions are never foretold. Political science classrooms do not teach about the art of such uprisings. However, when history's lessons are ignored, people stumble at every step. Politics influences the society. Whether an individual engages in politics or not, politics never leaves them alone.

After the partition of India, it took nine years for Pakistan to formulate its first constitution. However, it remained in effect for only two years. In contrast, Bangladesh adopted its constitution in a remarkably short time after independence. The constitution came into effect on December 16, 1972. That constitution has been amended 17 times over the past 52 years—not out of care, but out of political self-interest.

Once again, calls for constitutional reform and amendments have emerged regarding this. Ironically, those who were meant to govern have instead found themselves governed by the flaws within it. The reason for this is the ambiguities and contradictions embedded within the provisions and sub-clauses.

In this context, Akbar Ali Khan once quoted Abul Mansur Ahmad's ultimate solution for Bangladesh's constitution—that it must be truly democratic. Abul Mansur Ahmad wrote: "During the drafting of Pakistan's constitutional framework, I argued that instead of ensuring the protection of Islam, efforts should be made to safeguard democracy. For it is democracy that guarantees the protection of religion. Similarly, during the drafting of Bangladesh's constitution, I stated that socialism in Bangladesh is not at risk—democracy is. Cure democracy of its ailments, and socialism will inevitably thrive."

Agreeing with the views expressed in Amar Dekha Rajnitir Ponchash Bochor, Akbar Ali Khan said, "I was somewhat surprised. For quite some time, I had been saying these things, believing them to be my observations. But then I realised—I was merely reiterating what Abul Mansur Ahmad had said long ago. Our constitution is built on four pillars—democracy, socialism, nationalism, and secularism. My argument is that in a country where democracy does not exist, secularism can never be sustained in a meaningful way."

In this way, many of our most critical political thoughts have remained buried in obscurity. We seem to be trapped in an endless cycle, revolving around the same issues decade after decade, unable to find a way out—oscillating between political extremes under the guise of balance.

From the era of East Bengal to the early years of independent Bangladesh, Abul Mansur Ahmad raised sharp and intellectual questions about the constitution—most of which remain unresolved to this day.

We can still draw upon his ideas to navigate our crises. Thus, we may be able to restructure our society—one that we acquired at a great price. Otherwise, in the absence of democracy, we may be forced to shed blood once again!

Emran Mahfuz is a poet and convener of Abul Mansur Ahmad Smrity Parishad.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries, and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments