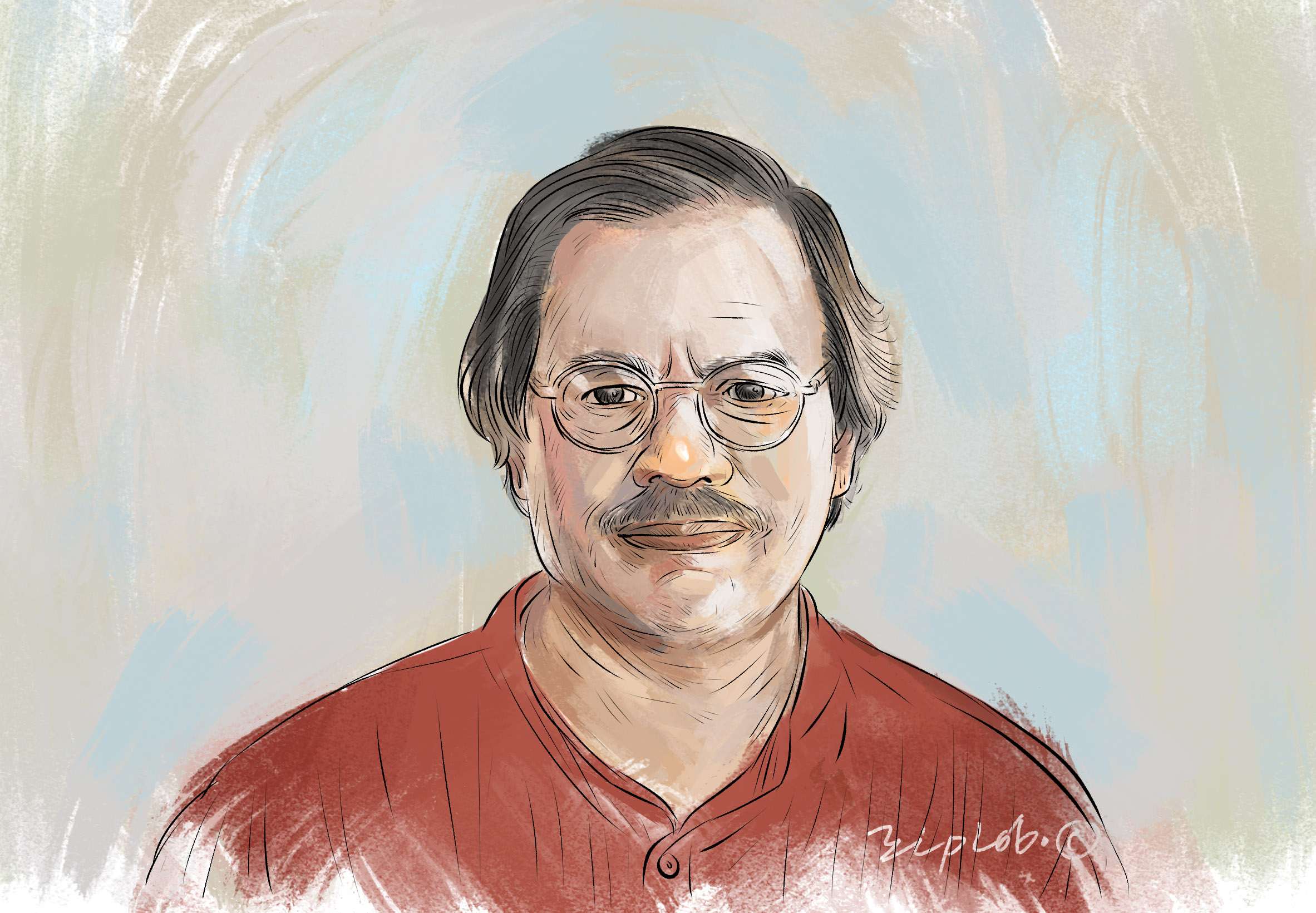

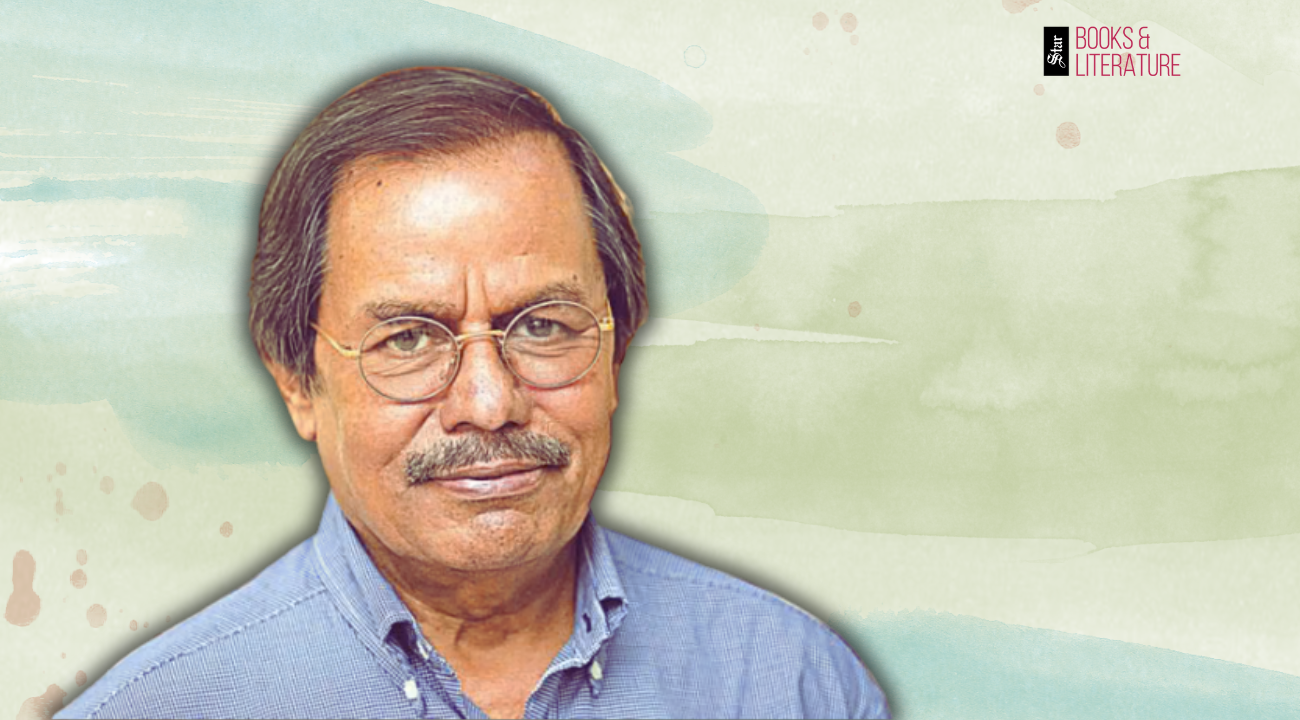

He moves still, in the gyres of our memory

It has been several days since the passing of Professor Syed Manzoorul Islam, yet I remain grief-stricken. I find myself asking: what is loss? Or rather, what is loss for those like me who have lost such a man? And what is loss for those who have never lived with such men?

As I travel back to the beginning, I recall—Manzoor da's doctoral thesis was on Emanuel Swedenborg's influence on WB Yeats. He had titled it "Gyres and Spirits," exploring Swedenborg's notion of spiralling motion and how it resonates through Yeats's idea of the gyre—an image that envisions histories and human consciousness as moving in intersecting spirals, ever-evolving, ever-rotating. I try to picture him as a young student walking the streets of Kingston in the late 1970s, his mind alive with ideas of motion. I think of Manzoor da's passing through this very idea of motion.

He loved Yeats. When it comes to death, the poet believed in the afterlife; Manzoor da did not. "I don't believe in the afterlife. Rather, I'm happy spending my life as a teacher. I'll be extremely fortunate if this happiness remains till the end of my life," he once said, and indeed, it did. Yet, he now gyres back as an element of nature through his merger, his burial.

Manzoor da never forgot to text me after Bangladeshi or Nepali cricket victories. I was revisiting some of those old messages yesterday morning. After Nepal's recent win over the West Indies, I had written, "It's amazing! What has happened to the West Indies?" to which he replied, "No, it's what happened to Nepal that is amazing! I guess Stuart Law is giving them a sense of confidence." Manzoor da was quite fond of Nepal. Whenever we invited him to a conference or a meeting, he would be there without any delay. The last time he visited Nepal was in 2024, as a keynote speaker at a conference.

He first visited Kathmandu 34 years ago for a literary conference. I remember the day he met my family for the first time. My daughter, Pallabi, was three. He bent down, held her face, and touched the tip of her nose with his. It took very little time for Soma, my wife, to find a brother in him. We laughed at how I had instantly become his jamai, the brother-in-law. "I have a sister in Nepal," he would often tell his friends. I cannot describe when or how our families became one.

Come to think of it, he never met our son-in-law, nor did we meet his daughter-in-law, but how lovely these two recent additions were in our lives was always part of our regular conversations. Once, I visited Dhaka without Soma, and Manzoor da chided me, saying I was "not welcome" there without his sister. The depth and warmth of his love were magnificent.

One day, I called him to complain about the nature of religious discourses and regressive foundational thinking in South Asia. He listened patiently as I said, "I'm detesting reading the Upanishads and Hindu texts on philosophical systems." "Why?" he asked. "Too much mediocrity in the use of these texts—people use them to propagate regression, division, and fundamentalism!" I replied. He said, "No, Arun! They are, as you already know, monuments of unaging intellect. All religious texts are, in their deep structures. You cannot read or unread them based on how people interpret them. You are Shreedhar's student. Go and talk to him again."

The regard he held for Professor Shreedhar Lohani was of a different league. Once, in Pokhara, I asked him about Shreedhar sir. "I feel like there are just two or three scholars left in South Asia who carry this dynamic oral tradition of the Socratic kind. Two of them are pirs or sadhus by the lonely hut and riverside, and one is your Shreedhar," he said. I never heard either Manzoor da or Shreedhar sir say this outright, but I often wondered if their shared fondness for Yeats might have drawn them to each other. In fact, Shreedhar sir had met him even before I knew either of them—at Oxford. Two days ago, when I told him the news, Shreedhar sir wrote, "I'm heartbroken, Arun. I will never go to Bangladesh." He meant it. His friend isn't there anymore.

As I write this, these lines from Yeats's cross my mind:

"Think where man's glory most begins and ends,

And say my glory was I had such friends."

It was 2018. Manzoor da and his wife, our boudi, had visited us, and we had gone to Nagarkot. It was that time of year when the icy peaks were still visible. We sat facing them, drinking tea. I remember asking him something along the lines of, "How does South Asia look when we discuss it from Bangladesh's perspective, or Nepal's, for that matter?" I don't remember his exact words, but recalling that conversation, he said something like this:

"Arun, it expands South Asia into a range of perspectives—the myths and sea discourse Kaiser (Prof Kaiser Haq) is writing about, Fakrul's (Prof Fakrul Alam) interregional literary sensibilities, or Abhi's poems, where he sees you beyond your room and sees us beyond ours. The Bangladeshi perspective can connect South Asia to Southeast Asia—the maritime silk route from Bengal, eastern Nepal, and India to China in the north. The cartographic vision can thus shape both similarities and contradictions in South Asian studies."

One cannot forget such nuances. His understanding of Islam was linguistically and vernacularly driven. "Arun, Bangla bhasha (language) will retain the culture of Bangladesh," he once told me. At another time, he said, "If languages are lost, the philosophies of religion go haywire!"

I had developed the habit of listening to people like Manzoor da and Shreedhar sir. They taught me the meditativeness of listening.

A week ago, as we do every year during Durga Puja, Soma and I called him to seek his blessings. He asked how we were, and Soma told him about our plans to return to Kathmandu from the US, where we were visiting our daughter, jamai, and granddaughters. "What is Jhinki (Pallabi) doing?" he asked. "Working away as usual," Soma replied. His response: "Tomra shobai dosh haathe kaaj kore jao, tomrai toh Durga" ("You all work with ten hands; you are the Durga"). It was always about perspective—I always learned that from him.

Just a week ago, before his passing, Soma and I were thinking about grandchildren—not just ours, but the very idea of them, the peace they bring, and the joy they radiate. We had just hung up after talking to Manzoor da, and Soma recalled his fondness for his grandchildren, and we reminisced about a funny story he once shared with us.

Once, while stranded in a city during floods, Manzoor da took his toddler granddaughter downstairs to see the water. As he held her, she stretched out her arms towards the puddles that the floodwater had formed inside their hotel. Glancing over his shoulder to see the father distracted, he quickly let her dip her feet in the water, and she splashed away happily. Upon returning upstairs, he carefully reminded the child that the splash was their secret. "But the moment she saw your boudi, she let it all out! Oh, her look!" he told us, laughing. Soma and I could picture his mischievous smile and the mock-fear on his face—like a child himself…

Manzoor da, the human child, who has now been stolen from us.

As I finish this piece, written in memoriam of Manzoor da, these lines from Yeats's "The Stolen Child" feel peacefully fitting:

"Come away, O human child!

To the waters and the wild

With a faery, hand in hand,

For the world's more full of weeping than you can understand."

Go, Manzoor da. Go with a fairy hand in hand. And here we remain, mourning this loss for the rest of our days.

Professor Dr Arun Gupto is academic director at the Institute of Advanced Communication, Education, and Research (IACER) and director of Comparative South Asian Studies at the South Asian Foundation for Academic Research (SAFAR) in Kathmandu, Nepal. He can be reached at akgupto@iacer.edu.np.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments