A good teacher teaches; an extraordinary teacher inspires

I have countless memories with Sir. I was probably the only student at that time who was in his tutorials for three consecutive years during my Bachelor's and one year during my Master's—essentially, for almost my entire student life at Dhaka University.

Our start wasn't easy. I was a little afraid of him, and he was rather strict. The first few tutorial classes were rough and left me quite disheartened. Baba would call and ask, "Does SMI know you are my daughter?". Ammu would say "Is Dadai taking any course in your class?" I kept quiet. What could I say? That he perhaps didn't like me or didn't think I was bright enough?

Our tutorials would take place on Saturday, early morning at 8:30. One day, he seemed to be in a bad mood for some reason and started to reprimand us. Then he suddenly turned his frustration toward the television: "It's a stupid box," he said, "and the whole world is staring at this stupid box! We are losing our intellectual growth watching TV!" There was pindrop silence. Sir, slightly tired after five minutes of continuous venting, when he was finally done scolding us, I softly responded (with the innocence of a child), "Sir, but sometimes we see you on that stupid box". The entire room burst into laughter, while Sir became startled, and probably a bit embarrassed too!

But he accepted the defeat and graciously responded laughing. "Well, yes, sometimes I do go there." (he was a frequent guest on talk shows around that time). The ice between us then broke. After that, every time I talked to him—about anything—there was always laughter.

It was during the early days of our classes. Sir was asking the tutorial students about their schools. One of our classmates replied that his school was in a village. "Not a school you would know, sir," he said. But Sir insisted. The student spelled it out and added, "You have to walk quite a bit to reach it." Sir nodded and said, "Yes, you cross the railway line, and then it's right next to it, isn't it?"

We were all surprised. Then Sir told him, "Why are you ashamed? You're the one sitting here with all of them. You've worked twice as hard and competed with this lot to earn your place. You should proudly say your school's name. Never shy away from where you come from." We all felt proud of our fellow classmate, and of ourselves as well.

At the beginning of my second year, one day after class, Sir called me to his room. He spoke about Baba at length and how he met him. Then, my mother came up. "Sir," I said, "Ammu calls you Dadai." He laughed heartily. "Minu is a friend of my younger sister, Baby. My sister used to call me Dada, but calling only Dada did not satisfy her, she had to stretch it further to something more affectionate— so, Dadai! Since then, I am Dadai to all her friends."

Before starting any syllabus, Sir would spend a few days discussing its time period— its architecture, politics, culture, climate, science, and the economy. He would say, "Literature is a reflection of its time. If you don't understand the era, how will you understand its literature?"

Once he explained how a country's climate influences its literature. People in colder countries, spending more time inside, tend to produce contemplative and introspective writing, whereas those in tropical countries express more emotion and passion. There were no exams in his tutorial class. My first-year tutorial presentation was a comparative analysis between Tess from Thomas Hardy's Tess of the d'Urbervilles and Parboti from Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay's classic Debdas.

Once, I told Sir that everyone at home had wanted me to study medicine, but I was not interested. Sir said to me, "You must make your own life decisions. Never to please others." That sentence stuck with me, and I have lived by it ever since.

I remember during our second-year finals—we were a bunch of English literature students, full of enthusiasm—feeling as though we could change the world through literature. We studied in groups and had deep intellectual discussions. One of us suggested, "Why limit ourselves to the syllabus? Let's study what is not in the syllabus. So we selected Sylvia Plath's "Daddy". We tried to analyse it but soon got lost. One of the "intellectuals" suggested we ask SMI to explain it to us. It was 3:30 in the afternoon; classes were over and Sir was in his room. Six or seven of us knocked on his door and entered the room with all the confidence in the world, as if the whole world would stop if we asked it to! Sir was sitting in his chair facing away, reading a book, a pipe in his mouth. We made our request; he looked mildly annoyed but said, "I can't give you much time, but sit down, I'll explain."

Somehow, one and a half hours went by. A room occupied by six-seven 20-year-olds, mesmerised, listening to the Maestro. He explained Sylvia Plath's childhood, her psychological conflicts, her relationship with Ted Hughes and her early death. There was a line in the poem: "ick, ick, ick, I could hardly speak." He explained that "ick" comes from the German 'Ich', meaning 'I'. Plath was gasping for breath, crying out—"I, I, I…"

For the next few days, I forgot that there was a syllabus for my exams and immersed myself in Sylvia Plath.

I can write a whole book about his classes—Marlowe, Shakespeare, John Donne, W.B. Yeats, Robert Frost, Shelley, Wordsworth—he taught them all. Yet I felt he loved teaching Postmodernism the most. My favourite, however, was his Master's class on Andrew Marvell's metaphysical poem "To His Coy Mistress".

Once he said in class, "The day you see a sunrise or sunset and feel nothing, the day you see a flower and can't stop for a moment to appreciate it, know that you have failed as a human being. Successful lives, brilliant careers are seldom worth living for, if you cannot appreciate life. What I want from you, my students, is to be humane and sensitive."

Sometimes, during class, he would give what he called a "commercial break." He would make witty, insightful remarks about anything and everything — the whole class would burst into laughter.

Once, he demonstrated how dancing in Hindi films works:

"It's simple—with one hand, unscrew a bulb; with the other, screw in another bulb; then shake your head as if you're drying your hair with a towel. And there you have it, a Hindi movie dance!" He even acted it out, leaving the class roaring with laughter. He was always on time, took all his classes, finished the course syllabus, and more.

During our Master's classes, once we went to his place for pizza. He claimed that he was the best pizza-maker in town, and it was true! He made three to four different types of pizzas, all delicious. The only condition was we would not clean the utensils. He did not have any house-help; he did not believe in it and did all household chores himself. We hung out, discussed literature, art, and politics. He gave us a tour of his beautiful house in Fuller Road. I loved his balcony the most. It had a beautiful bright red-brick wall full of masks hanging all over it, each collected from different countries. It was beautiful.

After my Honours, one day Sir called me and said, "Faridee is impossible! He called me the other day and said, "Monzur bhai, sorry. Over the last few years I did not answer your calls or get in touch. My daughter is your student. I didn't want you to think I was calling you to ask favours for her. That's why I stayed away. Now that she's graduated, tell me when we can meet. It's been so long since we had an adda.'" I was stunned. I knew my father hadn't spoken to Sir in a long time, but he never told me why. Sir asked, "Tell me, what am I supposed to say to that? Who even thinks like that?"

The day Baba passed away, I was completely devastated, confused, trying to wrap my head around what had happened. In the middle of the chaos, Sir called. "Debjani, your father was a wonderful man—honest, intelligent, brilliant, and kind. Always remember that. The whole country loved and respected him. Stay strong. He was very proud of you. And if you ever need anything, let me know." Only I knew how his words not only consoled a grieving daughter but also gave her strength to stand in that dark hour.

Sir and Baba both received the Ekushey Padak in 2018. I went to receive my father's medal. After the ceremony, there was a brief conversation and tea session with the then Prime Minister. The place was crowded. Sir stood next to me and said, "Do you think we'll get a chance to take a photo?" We did, though someone else joined us. He later asked me to email him the photo, and I cropped it to send just his part. He replied, happily stating that it was his favourite.

When Sir became Professor Emeritus, we were in London, wandering around the city with two of his dearest former students, Richie and Bulbul bhai. Sir called. He was elated, and so were we. That night, London felt more beautiful than ever.

The last time I saw Sir was at Bulbul bhai's book launch. Sabir and I had even planned to invite him and a few others to our home for an evening adda. That plan never happened.

My outlook towards life has been profoundly influenced by SMI. Somehow, I had taken it for granted that Sir would always be there. How could he not? I knew that if I were to peek through his window in front of the English Department office, I would see him sitting in his chair, turned backward, a book in hand and a pipe in his mouth.

How can he not be there?

Today, I stood quietly for a while in front of Room 2064 on the second floor of the Arts Building—a place where I had stood countless times before, each time leaving with his warmth and affection.

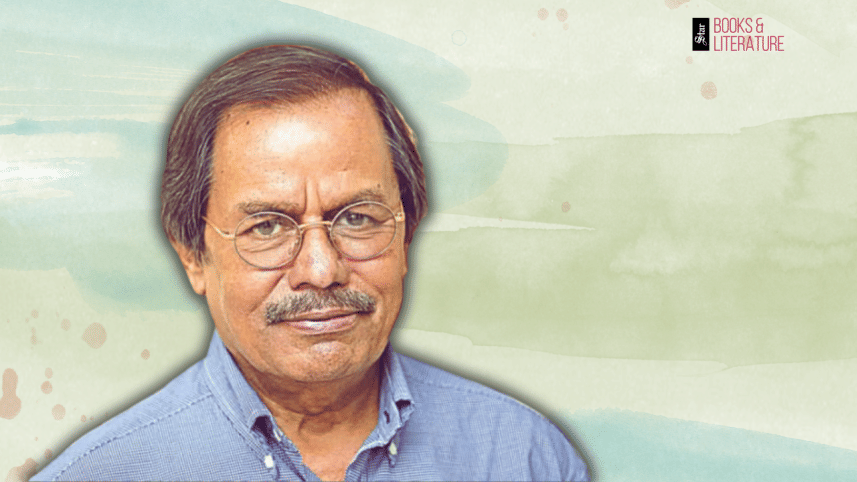

Sir once said in an interview, "A good teacher teaches; an extraordinary teacher inspires". Who could know the truth behind this better than his own students?

The greatest achievement of my life is that I was his student.

Rest well on the other side, Sir. And when my time comes, perhaps I will sit once more in your class! Some classroom in the lecture theatre building will once again echo with your voice:

"Let us go then, you and I,

When the evening is spread out against the sky

Like a patient etherised upon a table."

Shararat Islam is a development professional and a student of Syed Manzoorul Islam.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments