Gendered struggles in urban transit

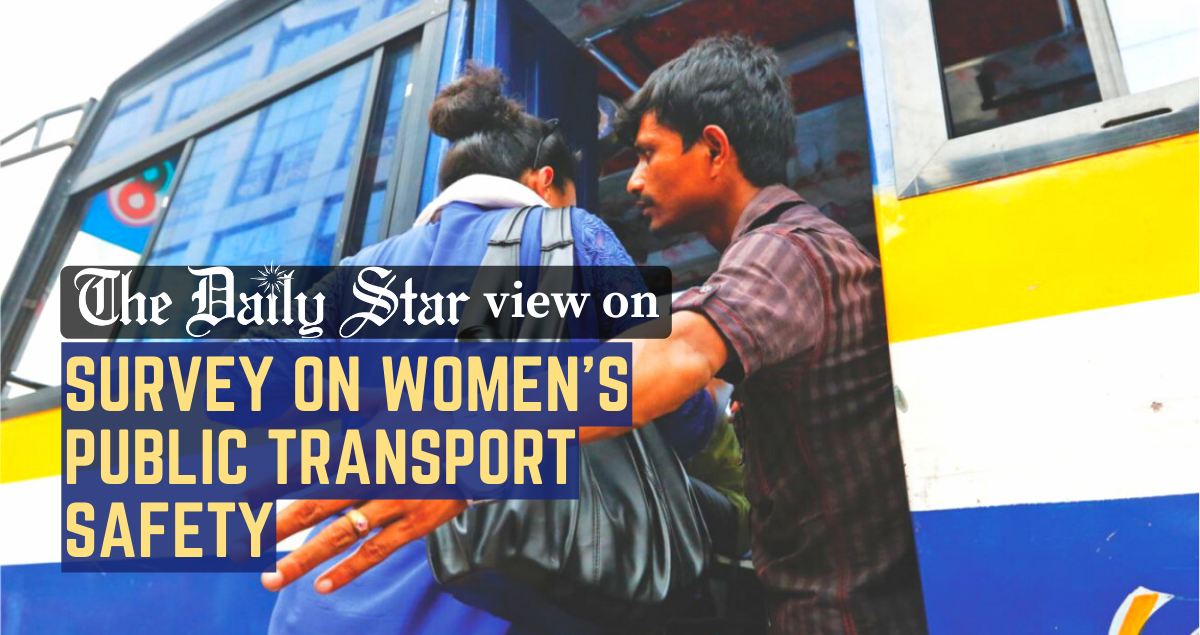

A friend recently shared an anecdote about the new Dhaka MRT Line-6. She said her relative was on a crowded train one morning during rush hour when he witnessed a group of men telling a young woman to go to the women-only carriage at the front. They said her presence was forcing them to stand away from her to avoid unwanted physical contact. They viewed her as an inconvenience because she was taking up space where other men could have been standing. But she stood up for herself and told them to leave her alone. She said the metro was built to accommodate all commuters and that women have the right to choose any carriage of the train for their journey. While her words are true, this incident demonstrates the larger issues of gender inequality in Bangladesh's urban spaces.

Women-only transport is not just a phenomenon in Bangladesh but also available on trains, subways, and buses around the globe, including in Brazil, Egypt, India, Japan, Mexico, and Taiwan, among others. They were initially implemented as a safety measure for women because sexual harassment and assault are all too common on public transport. But the question remains as to whether they actually work to decrease the incidence of violence against women or if they instead perpetuate the gender discrimination that women face in public spaces.

Dhaka's metro rail may be fairly new, but women have been facing barriers to their urban mobility since long before. With public buses in Dhaka, for instance, the initiative to address issues of women's safety led to mandated women's seats on vehicles from 2018. Yet, many women have complained to me that this policy is barely enforced other than for government-operated transport services. Depending on the bus, the first two to three rows of seats are reserved for women, older persons, and persons with disabilities. But sometimes, young and able men ignore the rule and occupy those seats regardless.

A few weeks ago, I boarded a bus with no seats available and barely any room to stand. I was wedged between multiple people and standing next to a woman sitting in the second row of seats. She turned to me and said she would be getting off after a few stops and that I could take her seat. I thanked her, and just as her stop approached, I moved forward to let her and others behind me disembark. It was so crowded that I had to lean over the women sitting in the first row to make space for others who were squeezing past me. After a minute or two, as people finished getting off the bus, I moved back expecting to sit down on the seat the woman had offered me earlier. However, I was disappointed to find that a man had conveniently taken a seat there instead. I looked at the man for a few seconds, but he avoided making eye contact. He was typing something on his phone. The woman next to him took notice and informed him that he was sitting in a woman's seat and that I had been waiting to sit down. He continued to ignore us both. After the lady repeated herself for the third time, the man became flustered. "Uff!" He exclaimed. "Which women's seats?" he asked loudly. "If you women truly want to be equal to men, why would you want to receive special treatment?" The woman and I looked at each other knowingly. Nobody else around us said anything. The bus conductor lit a cigarette and continued to stare out the open door.

Experiences on public transport, like mine and of the woman on the metro train, highlight the casual dismissal of women's rights to equal access and treatment in public spaces. Despite the implementation of measures like women-only carriages and reserved seats on public buses, the reality often falls short of intended outcomes. While these measures were initially introduced to counter the prevalence of violence against women in public spaces, their effectiveness remains a subject of debate.

The response of men towards women's presence in public transport reflects deeper societal attitudes towards gender equality. Men's assertion that women should not seek "special treatment" if they strive for equality underscores a pervasive misunderstanding. It suggests that women are seeking preferential treatment rather than striving for a level playing field. Consequently, men continue to resist acknowledging the structural barriers and gendered discrimination. They fail to empathise and instead normalise the prejudice that women face every day.

Ultimately, stories like those mentioned above underscore the urgent need for comprehensive efforts to address gender inequality in cities, including robust enforcement of policies, public awareness campaigns, and the promotion of inclusive attitudes and behaviours. Only through concerted action can we create cities where all individuals can navigate public spaces safely, comfortably, and with dignity.

Anushka Zafar is a PhD candidate of International Development and Anthropology at the University of Sussex, UK. Her research examines women's public transport use in Dhaka city.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not reflect those of any organisation, institution or entity with which he is associated.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments