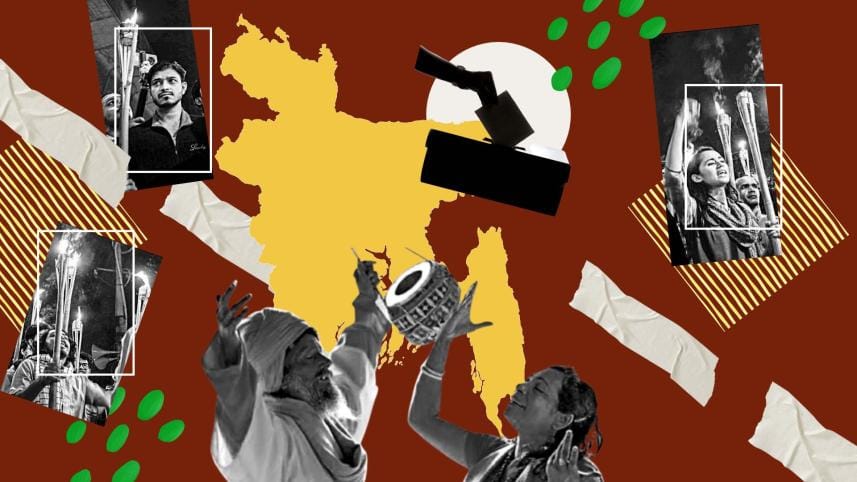

Bauls, ballots, and the price of weak institutions

The surest sign of a liberal democracy is not a flag, nor a constitution framed behind glass. It is the quiet competence of institutions—and the political culture that keeps them honest. One shapes the other the way a river shapes its banks, and the banks, in turn, discipline the river.

That is why the institutionalists keep returning to the same blunt lesson: prosperity and stability do not emerge from slogans, but from rules that bind the powerful and protect the ordinary. The modern canon has made this point in different registers—economists Daron Acemoglu and James A Robinson's popular formulation of "inclusive" institutions, for instance. Besides, many other scholars have helped renew attention to the study of institutions within top-tier economic and policymaking research. Harvard Business School Professor Tarun Khanna and colleagues, writing from the trenches of emerging markets, named what citizens live with daily: "institutional voids"—the missing intermediaries, enforcement mechanisms, and credible regulators that make markets and democracies functional rather than theatrical.

Liberal democracy is a system of habits: impartial policing, predictable courts, professional bureaucracy, disciplined parties, a press that can wound vanity without being silenced, and a citizenry that does not confuse allegiance with worship. When these habits rot, ballots become costumes in a performance.

In a country like ours, religion supplies a large share of the moral vocabulary that becomes political culture. It is sociology. But it becomes combustible when a single, increasingly literalist and punitive style of religiosity pushes itself into every public space—especially in a society where state institutions are weak enough to be bullied by the loudest. Bangladesh's recent history has seen surges of conservative identification; in the streets, this often takes the form of "guardianship" over women's bodies, music, folk spirituality—over anything joyful that cannot be easily policed.

Political scientist Samuel Huntington's "Clash of Civilizations" thesis was never merely descriptive; in practice, it became a script that actors on all sides could perform. When global politics is reduced to civilisational camps—"the West" and "Islam," each imagined as a single block—religion is pushed into the role of political identity, not only private faith.

Under Sheikh Hasina's long authoritarian arc, a particular narrative was sold abroad: the state as the last rampart against Islamist extremism. And authoritarian states love a single monstrous enemy; it lets them call every democratic demand "instability." After the 2024 uprising, Bangladesh entered a new period. What came with the regime's fall was not only relief; it was revelation—the true depth of institutional depravity, now visible because fear no longer covers it.

We are now scheduled to hold national elections on February 12, 2026. Yet, the air is still thick with the sense that rules do not rule; forces do. There is rising dissatisfaction with the interim administration amid delays on promised reforms, with renewed protests and tensions.

In such a vacuum, the street becomes the parliament, and the most organised intimidators become lawmakers.

Since August 2024, we have watched extremist voices test the state's reflexes. In March 2025, police used tear gas and sound grenades to disperse a "March for Khilafat" in Dhaka involving members of Hizb-ut-Tahrir, a group banned since 2009 yet bold enough to mobilise publicly after Friday prayers.

Then came the policing of women's public presence—not through law, but through vandalism and menace. In late January 2025, women's football events in Joypurhat and Dinajpur were cancelled after violence and pressure from groups identified as "Towhidi Janata," with injuries reported; even when authorities later ordered rescheduling, the message had already been delivered: women may play only by permission.

Around the same period, multiple prominent actresses did not attend planned public programmes, with reports of security concerns and local opposition surrounding such events.

And when the interim government's own Women's Affairs Reform Commission produced a report with hundreds of recommendations, backlash turned grotesque. Viral images of men beating a sari-clad effigy of a woman with shoes on the Dhaka University campus and reports documenting derogatory public rhetoric against the commission and demands to abolish it became common.

This is the context in which the latest target has appeared: the bauls—Bengal's wandering metaphysicians, singing devotion without bureaucracy. Unesco describes baul songs as an "unorthodox devotional tradition," influenced by multiple strands including Sufi Islam, yet not reducible to any organised religion.

In November 2025, "Maharaj Abul Sarkar," a prominent baul singer, was arrested and sent to jail in Manikganj for allegedly hurting religious sentiments. The allegation was related to remarks during a folk performance earlier that month. After the arrest, attacks were reported against bauls and Abul Sarkar's followers in Manikganj and elsewhere.

Here, the cultural war becomes unmistakable. "Bengali nationalism" and "Bangladeshi nationalism" have carried multiple meanings across history, but today they are often waved like opposing flags: one associated with an indigenous Bangalee culture that includes Islamic components, the other increasingly framed by some as a narrower religious identity suspicious of folk traditions. In that zero-sum contest, bauls are condemned not for violence, but for ambiguity—for refusing to fit cleanly into the boxes.

There is an irony worth underlining for the pious and the political alike. Conservative gatekeepers sometimes cite Imam al-Ghazali as a warrant for crushing "deviant" spirituality. Yet, al-Ghazali's own legacy is more complex: he famously attacked certain metaphysical claims of the philosophers in The Incoherence of the Philosophers, while his broader work helped make Sufism an acceptable part of orthodox Islam. And in Bengal, encyclopedic scholarship notes that Sufi saints and syncretistic practice were central to Islam's spread and its accommodation with local culture.

I have personally sat through a Friday sermon where a khatib described bauls as people who eat human excrement—malice dressed up as piety. Even if one believes baul metaphors cross theological lines, the cruelty of the propaganda is not proportionate to any alleged deviation. It is not da'wah; it is dehumanisation. And dehumanisation is how mobs prepare themselves.

So, the question institutionalism forces upon us is not only who is right, but who benefits when the state looks weak. When extremist street-power rises visibly in the absence of an autocrat, it can retroactively validate the autocrat's propaganda: "Only I can control the monsters."

In such conditions, any manufactured chaos becomes a bargaining chip—domestically and internationally.

To preserve democracy, we must reject extremist intimidation on principle. But we must also reject it tactically in the short term, because chaos is a currency spent by those who want to discredit electoral politics and re-legitimise authoritarian "order."

What should be done is, in fact, unromantic: enforce existing law consistently; prosecute violence regardless of banner; protect women's sports and cultural gatherings as ordinary public order duties, not "special permissions"; and defend freedom of expression without waiting for international embarrassment. Above all, rebuild institutional reflexes—police that respond to crimes rather than crowds, administrators who do not surrender the state's authority to whoever shouts loudest, and political parties that stop outsourcing public morality to mobs.

A democracy does not die only when a dictator returns. It also dies when citizens learn to whisper. And nothing teaches us to whisper faster than the sight of a state that will not stand between the vulnerable and the violent.

Bobby Hajjaj is chairman of the Nationalist Democratic Movement (NDM) and a faculty member at North South University. He can be reached at bobby.hajjaj@northsouth.edu.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries, and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments