Bangladesh-India ties: A tragicomedy where populists take centre stage

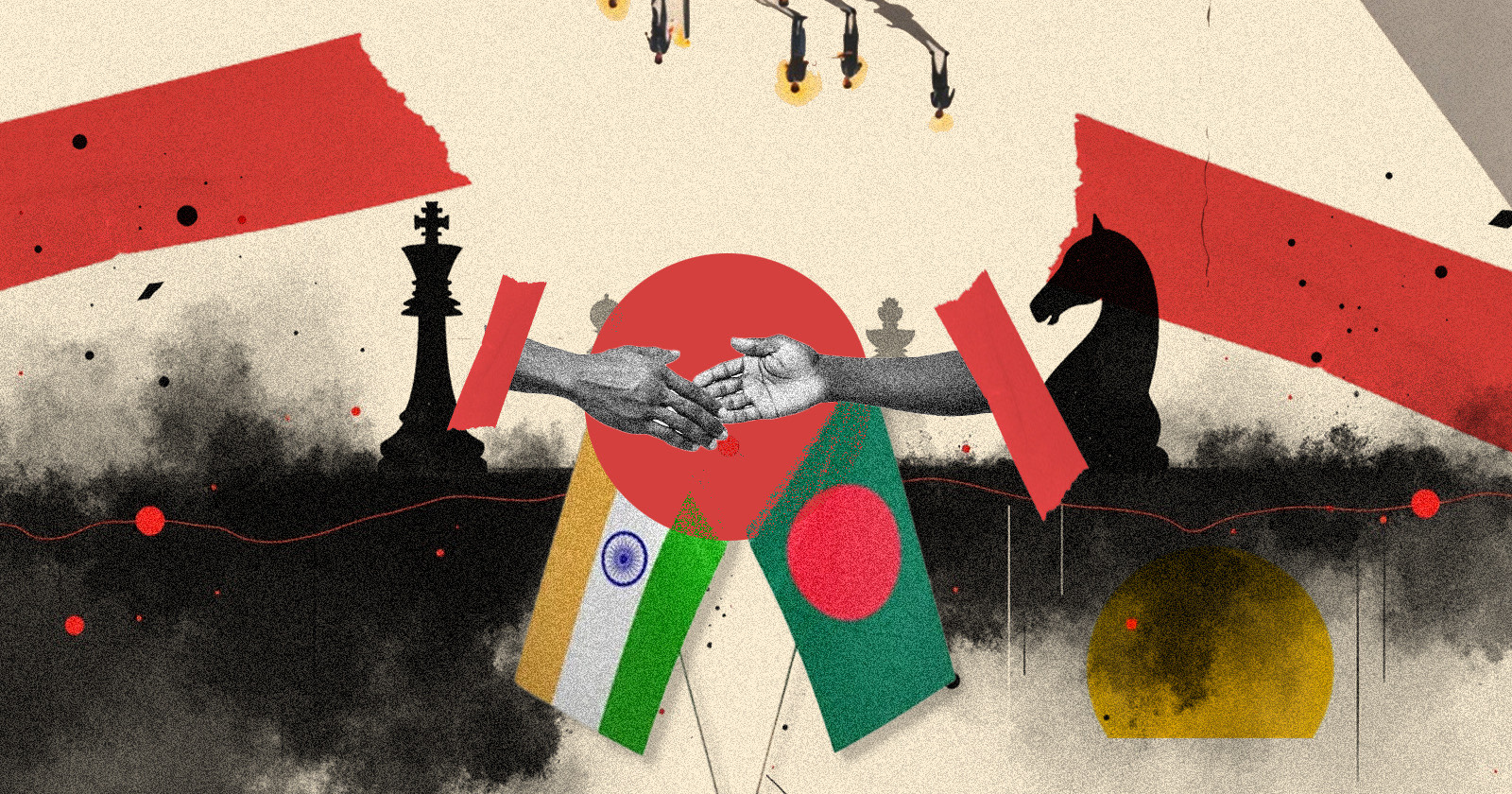

There is a tragicomedy in watching two neighbouring countries bound by geography drift apart like two sailors jumping ship in different directions, each convinced the other is sinking faster. This applies to both Bangladesh and India that have apparently decided, one more than the other, that centuries of shared culture, cuisine, and history are insufficient grounds to maintain even basic norms of engagement. What we are witnessing today is not merely a diplomatic crisis. It is a masterclass in how not to conduct foreign policy politically.

At the heart of prevailing tensions lies the narrative of extremism, a trusted old poison that keeps on giving. As Shakespeare would say, "A plague o' both your houses!" Mercutio's dying curse feels uncomfortably apt for what we are witnessing. Two nations seem determined to forgo civility in their relations, while extremists on both sides profit from the carnage. It is a show in which mobs replace politicians, and media and WhatsApp gladiators substitute for statesmen.

In India, saffron extremists and propaganda machines have found Bangladesh to be a convenient punching bag—a replacement for the increasingly inconvenient Pakistan or China cards. The "termites" rhetoric, periodic stray comments on Bangladesh's sovereignty, BJP's Mamata factor, and prime-time studio shouting champions have together achieved what decades of politics could not: they have united Bangladeshis across party lines in irritation with Delhi politics.

But let us not pretend that extremism flows only downstream from the Ganges. Bangladesh's interim government today presides over a landscape where the mob culture has become a lived reality, displaying a persistent inability to counter violence effectively. Whether helpless or an accomplice in this episode, the government cannot escape responsibility for the rise of these violent forces. To be fair, post-uprising volatility is hardly unprecedented. But prolonged inaction only emboldens those who thrive on chaos.

India's predicament, on the other hand, is self-inflicted. Having bet heavily on Awami League for so long, Delhi now faces genuine anti-Indian sentiment—not propaganda, just consequences. Meanwhile, India's political and social hysteria since July 2024 continues to feed on narratives repeatedly debunked by objective media, yet the religious card keeps being played. Of course, we cannot deny that minorities face some threats, but so do the general public.

Delhi's selective amnesia in this regard are almost amusing. It conveniently forgets that the demands of the July 2024 uprising were apolitical and met with state bullets before the eventual ouster of the Awami regime. Saffron politicians might do well to tally their own cards, assuming that they are still capable of moral self-reflection. The absurdity has peaked most recently when Siliguri hoteliers imposed a ban on Bangladeshi tourists. Apparently, extremism now checks passports at reception. One doesn't need to imagine what the Indian public have been fed about Bangladeshis all this time.

It is also evident that Indian politics is experiencing what diplomats might politely call "challenges." These challenges relate to some harsh reality checks. The Trump administration delivered reality check number one: Washington, it turns out, has little patience for hegemonic ambitions unsupported by regional clout. The trade imbalance with China offered reality check number two, as fiery anti-China rhetoric at domestic rallies does not equal decoupling. The Pahalgam fallout brought reality check number three, as political choruses solve nothing. And the fourth is a classic: Dhaka, once the BJP's favourite electoral dish, has left the table.

Is blaming Bangladesh fair, then? Let us not forget that Professor Muhammad Yunus had wanted to visit Delhi before Beijing, and has tried to engage politically on various occasions. Delhi's response? Continued disengagement, suggesting a preference for sulking over statesmanship until Bangladesh holds the elections. Diplomacy requires reading the room, but Delhi appears content to wait outside.

This inaction enabled mobs in Delhi's security heartland, Chanakyapuri, to stage an arrogant spectacle against the Bangladesh High Commission, following similar incidents in Agartala and Kolkata. High Commissioner Riaz Hamidullah's professional response to denial of mob activities by his counterparts deserves to be studied in diplomatic academies, as do the political failures that made such scenes possible in the first place. Indian High Commissioner Pranay Verma, it should be acknowledged, also showed professionalism, refraining from publicly sensationalising diplomatic summons.

Yes, some protesters attempted to march towards Indian diplomatic missions in Bangladesh. There have been regrettable incidents of stone-pelting as well. But the Indian response came from the same crowd peddling Akhand Bharat, while periodically questioning Bangladesh's sovereignty. Sanity has, however, prevailed for now. Both governments have taken steps to prevent further escalation and to protect diplomatic premises. The question worth asking is this: what did those who mobilised mobs against diplomatic missions expect to achieve?

Indians must accept the reality that they will have to maintain even-handed relations with Bangladesh regardless of which party governs in Dhaka. Bangladeshis, for their part, must accept that India cannot, and will not, de-securitise its relationship with its eastern neighbour given its national security compulsions. But there lies a political lesson, too. Delhi, having lectured Bangladesh on extremism for years, now finds itself courting the Taliban. When your diplomatic dance card includes the very extremists that your own rhetoric previously vilified, your moral high ground starts to look suspiciously like quicksand.

Meanwhile, Beijing and Washington watch from the balcony as two key partners in their respective Asian strategies squabble over the last samosa while the restaurant burns. Both know this antagonism serves neither their interests nor regional stability. They might have found it entertaining had geoeconomics not chosen this precise moment to redraw the geopolitical map.

What, then, must be done?

Bangladesh must ensure its domestic security ahead of the 2026 elections, which will determine its future stability. The armed forces, bureaucracy, and political parties must forge an immediate consensus to maintain order and neutralise extremism, wherever it originates. Bangladesh should remain open to normalisation with Delhi. Reciprocity, naturally, is non-negotiable.

India, meanwhile, should seriously consider whether its current approach serves any purpose beyond feeding nationalist television. Minority persecution in India, documented year after year in international religious freedom reports, has not gone unnoticed, while restricting people-to-people contact has only proved counterproductive. Walls may make headlines, but bridges make progress. For Delhi, the homework is simple: It has to understand where Dhaka's red lines on sovereignty, autonomy, and foreign policy now stand.

Both nations face a more or less similar reality on the ground. Crises continue to pile up while populists promote their own versions of the Crime Master Gogo, the hilariously delusional villain from Bollywood's cult classic Andaz Apna Apna, convinced of his immense power while the world laughs. The time has come for veteran politicians to decide whether to continue this tragicomedy or accept that geography is destiny, and as such must be managed through restraint and reciprocity—not out of affection, but rather cold pragmatism.

I remain optimistic that politicians and diplomats will eventually stumble upon pragmatism at some point. Until then, someone should tell the spokespersons, partisan hype merchants, and assorted Crime Master Gogos that they are not helping. At all.

Professor Shahab Enam Khan is executive director of Bangladesh Center for Indo-Pacific Affairs at Jahangirnagar University, and teaches at the Bangladesh University of Professionals.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries, and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments