Ahmad Rafique: A story that must not fade away

I first heard this tragic story 11 years ago from Ahmad Rafique himself. It is a story of his personal defeat, humiliation, and rejection. At the same time, perhaps it is also a reflection of the countless "hijacked revolutions" of this land.

It was on a February afternoon in 2014 that I first met Ahmad Rafique in person. A small, informal meeting about the use of the Bangla language was organised by someone at Dhaka University's Teachers' Club. However, hardly anyone attended. As a result, instead of the meeting, we had a lively adda making the most of our time. Ahmad Rafique told us how, along with a large and enthusiastic group, he had taken a remarkable initiative to translate medical science textbooks into Bangla. He also told us how that promising project was ultimately dismantled.

The story was so depressing that it stayed with me for years and grew increasingly unsettling in my mind. So, seven years ago, on the evening of February 19, 2017, encouraged by Zahid Sohag, literary editor of Bangla Tribune, I went to Ahmad Rafique's house. I had the strong urge not to let this story vanish. Even a history of failure—such as how, after the most extraordinary beginnings, we are eventually dragged back to the starting point—needs to be recorded. Sitting in his simple living room, Ahmad Rafique spoke:

"I have always been an advocate for education in Bangla, not just at the primary level, but in higher education. Studying medicine is quite complex. Many students, after writing excellent answers in written exams, stumble and stammer in oral exams, as it is difficult to express what one knows in another language (English). Then the examiners think the student knows nothing. In consultation with Bangla Academy, I had Davidson's Principles and Practice of Medicine and Cunningham's Manual of Practical Anatomy translated by different people. I was on the editorial board, along with Sayeed Haider, and later, Subhagata Choudhury joined us."

Thus, the first phase of the medical translation project was completed. This was in the early 1980s. The real success would have been if students had actually studied and used them successfully in their professional lives. But what actually happened was beyond imagination.

"When those books were in the warehouse, Haider and I went to meet the principal of Dhaka Medical College. I don't remember who he was. Another professor was also sitting there. They all said, 'How is this possible! How is this possible!'

It was quite frustrating. I mentioned hearing that the engineering university started offering alternative question papers in Bangla so that students could write answers in their native language if they wanted. I argued that if exams were held in Bangla, students would perform much better. But nothing came of it.

The principal said, 'So many new researches are coming out in English.' I said those could be included in the next editions. I told them, 'You were a student and so was I; we both know that if students could answer in Bangla, they would express themselves much more easily.' But there was no result. The books were left in Bangla Academy's warehouse to be eaten by termites. Hundreds of thousands of taka were wasted."

Terminology and classism

Ahmad Rafique considered translating those textbooks because of his long-term involvement with Bangla terminology. Recalling those days, he said:

"Everyone talks about the problem of terminology, so I created the Medical Science Terminology Dictionary. Before me, Bangla Academy had a very small terminology glossary. Another friend of ours, Dr Mortaza, a doctor at Dhaka University who was martyred in the Liberation War, had worked on that. When Bangla Academy asked me, I added several thousand words to it. I expanded and refined many terms. Bangla Academy published it. Later, I also published a magazine called Paribhasha (Terminology) for some time. Then came the Chemistry Terminology Dictionary, Physics Terminology Dictionary, Botany Terminology Dictionary…

But while the terminology dictionaries were being published, giving exams in Bangla was being banned on the pretext of a lack of terminology!" Ahmad Rafique grew a little agitated: "I say, terminology is not a problem at all. The problem is in our thinking. It's a class problem. The class that holds economic and social power, if they make education accessible to all, and if more students come in, they will face greater competition."

But Ahmad Rafique did not believe in blaming individuals. He said, "Even the other day, a woman told me that her child was punished for speaking in Bangla."

Then why are parents sending their children to English-medium schools? The reason is simple: otherwise, they will fall behind in the race. If the standard is not knowledge itself but the ability to read and write in English, no parent would want their children to lag in that competition.

"So, I don't blame the parents anymore. I blame the state, the system." This system is not about individuals. It is the class in power that, through the language of its dominance, draws newcomers or drags them into the same competition, he explained.

In search of lost books

After returning home, realising I hadn't even seen the books, I troubled the old man again. With a tone of sorrow, he told me that he had no copy. He had changed houses so many times that they had disappeared somewhere.

The books that were supposed to be present in every medical student's home were not even with the person who created them! He said if not in Bangla Academy, they may never be found.

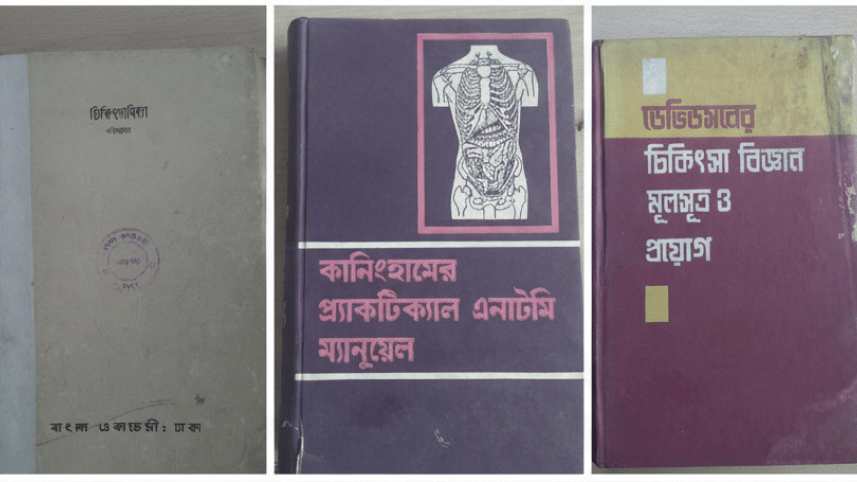

The books did not vanish entirely, however; they survive like relics. On the morning of February 20, 2017, Zahid Sohag and I went to Bangla Academy and saw them: Cunningham's Manual of Practical Anatomy and Davidson's Chikitsya Bigyan: Moolsutra o Proyog (Principles and Applications of Medical Science) in two volumes, and the Medical Science Terminology Dictionary—all silently sitting in the dust-covered library. As I turned the pages, I saw the year 1983—and the names of Ahmad Rafique, Sayeed Haider, and Subhagata Chowdhury gleaming brightly.

The project did not bring about a revolution; it ended in failure. Yet it will remain a noble example of an effort to write the history of higher education in Bangla—a project born of immense labour and love for the language.

Ahmad Rafique is not defeated, nor is Bangla. There has been a temporary retreat, however. What could have been achieved did not happen due to non-cooperation, arrogance, and covert or overt conspiracies, sometimes even through the sabotage of institutions.

Bigger picture

Had the Dhaka Medical College approved Ahmad Rafique's initiative back then, it could have marked the beginning of a major transformation in our higher education system. Inspired by his endeavour, many young people had also joined the cause. Let me quote from a reminiscence by Dr Khairul Islam:

"We came to know that Bangla Academy had taken up a project to translate various English academic books into Bangla. They were eager to translate medical college textbooks. Language veteran Dr Ahmad Rafique and his friends dared to translate Davidson's Medicine. We decided to translate Midwifery by Ten Teachers. We went to Bangla Academy.

Thus, under the editorship of Suraiya Jabin, Midwifery by Ten Teachers was translated into Bangla in two volumes in 1988, with the names of Khairul Islam, Liaqat Ali, and Khosru Islam.

This translation work met the same fate. It was also never reprinted. In a dynamic field like medical science, these books are now no more than relics. But this event is a relevant example of why our nation still lacks meaningful access to the realm of science. In the meantime, countries like China, Malaysia, Thailand, Iran, Korea, and many others have fully mastered modern medical science in their native languages. The initiative to translate medical science into quality Bangla, which the entrenched establishment did not allow to advance, is now slowly creeping into the market as informal, often rote-learning-based books, as medical education expands.

The Language Movement of 1952 changed the lives of many young people forever. Matin, Tohaha, Oli Ahad and many others devoted their lives to politics. Many others, while staying close to politics, tried to carry out other sociocultural responsibilities their entire lives. Ahmad Rafique is one of them. Not only did he seek to faithfully record the memories and history of the Language Movement, but he also remained ever-alert in his efforts to rebuild society in its spirit.

Firoz Ahmed is a member of political council, Ganosamhati Andolon and former president of Bangladesh Chhatra Federation. He has also served as a member of the Constitutional Reform Commission under the interim government. The article was translated from Bangla.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments