Managing our external debt needs a balanced strategy

The global public debt has reached an unprecedented level, raising concern among all stakeholders. The amount stood at $102 trillion in 2024, a $5 trillion increase from 2023, according to a recent report by the UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Several factors, such as government borrowing during the Covid pandemic, rising interest rates, and a slowing global economy, drove this surge. For low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and least developed countries (LDCs), which are already grappling with limited fiscal space and development challenges, a rising public debt has far-reaching consequences.

High levels of debt constrain a government's capacity to invest in essential development areas, such as healthcare, education, infrastructure, and climate adaptation. Debt servicing, which encompasses the cost of paying back the interest and principal amounts, is consuming an increasing share of national budgets. This constricts spending on public services, which is already limited in poor countries. Interest payments account for a significant portion of government revenue in developing countries. The net interest payment on public debt made by developing countries reached $921 billion in 2024, a 10 percent increase compared to 2023.

The composition of debt is changing over time. Developing countries are increasingly borrowing from private creditors and international capital markets, rather than relying on concessional loans from multilateral institutions. This allows access to larger sums of finance. However, it comes at higher interest rates and shorter maturities. This increases these countries' vulnerability to global financial shocks.

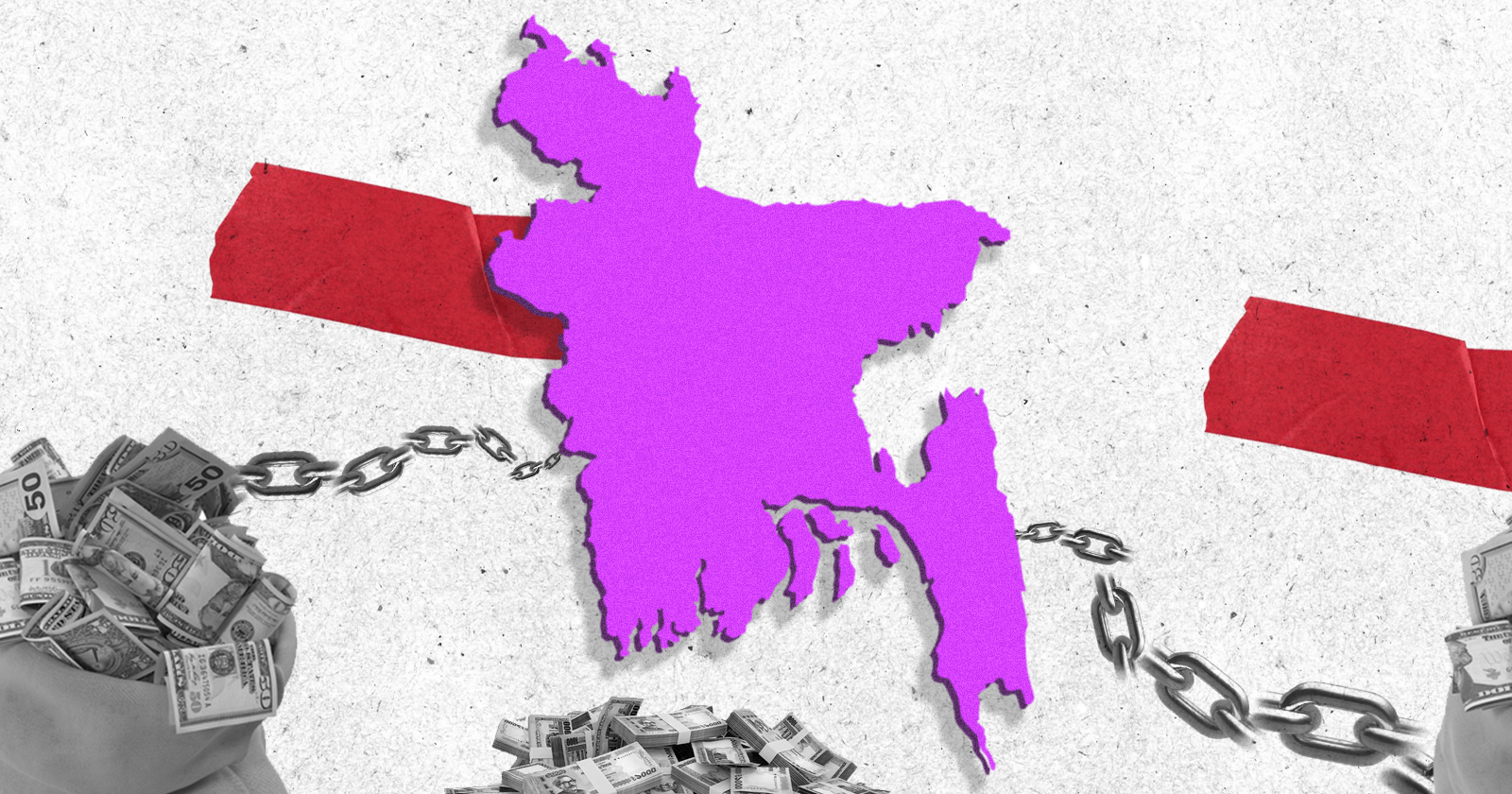

For countries like Bangladesh, which aspires to the upper-middle-income status while preparing for graduation from the LDC category in 2026, this trend presents both challenges and opportunities. In Bangladesh, debt levels have risen steadily over the past decade, becoming a pressing issue in recent years. Although the debt situation is manageable as per the international benchmark, the rising cost of repayments is worrying. Foreign borrowing has become more expensive due to higher interest expenses, a larger share of non-concessional loans, and tougher lending conditions. Due to limited foreign exchange reserves, the strain of repayment is felt more. The cost of debt servicing is rising due to an increase in global interest rate and currency volatility. Since Bangladesh borrows mostly in US dollars, repayments become more expensive when the taka depreciates.

Bangladesh's external debt, which has been around $100 billion in recent times, may not seem extraordinary when compared with other developing countries. But the challenge emerges when this debt is compared against the country's earnings. Nearly 80 percent of the debt belongs to the public sector, while the rest to the private sector. In 2016, the country's foreign debt was equal to just over half of the value of annual exports. Now the debt amounts to more than the full value of exports. Debt compared to government revenue has also increased significantly. With a tax-GDP ratio of around 7.4 percent in FY2024, the government has very little fiscal space to manage this growing burden.

The terms of borrowing have also changed. Since Bangladesh became a lower-middle-income country in 2015, it lost access to cheap, concessional loans. Interest rates from the World Bank, Asian Development Bank (ADB), and Japan International Cooperation Agency (Jica) have nearly doubled, while grace periods and repayment schedules have become less generous. Some loans are linked to global floating interest rates. For example, the benchmark Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) is now above five percent, compared to less than one percent only a few years ago. Bangladesh's annual repayment of foreign loans rose from about $3 billion in FY2013 to over $4 billion in FY2023.

These repayment pressures are surfacing at a particularly difficult moment. The economy is facing high inflation, limited forex reserves, weak revenue collection, and low investment. Therefore, external debt, which can be a tool to fund growth, can also turn into a burden if not managed efficiently. The government also borrows from domestic sources to finance the budget deficit. Although the budget deficit remained below five percent of GDP, reliance on the banking sector has increased as a domestic source of funding.

For Bangladesh, adopting a balanced strategy is crucial. The government needs to be careful in financing development while maintaining debt sustainability. It must expand concessional borrowing from multilateral development banks. Such funding is critical for infrastructure, climate adaptation, and social protection programmes at low cost. At the same time, the country should also explore innovative funds. For example, debt-for-climate swaps where a portion of external debt is forgiven in exchange for investments in climate-resilient projects. Such mechanisms can reduce debt burdens, while also helping reduce climate vulnerabilities.

Another critical avenue is domestic revenue mobilisation. While external debt remains significant, Bangladesh can reduce its reliance on borrowing by improving tax collection and broadening the tax base. Clearly, countries with stronger domestic resource mobilisation are better positioned to sustainably manage debt and invest in long-term development. Higher tax collection should be coupled with efficient public spending. That requires transparency in borrowing and investment so that debt translates into tangible benefits rather than creating fiscal pressure.

In a world of economic pressure and uncertainty, characterised by trade protectionism and currency fluctuations, Bangladesh must diversify its sources of financing and build financial resilience to withstand global shocks. It needs to adopt sustainable financing strategies to avoid debt crises. Debt is not inherently bad, unmanaged and excessive debt can erode growth, social welfare, and resilience. With prudent policies, careful planning, and innovative financing strategies, Bangladesh can harness debt as a tool for sustainable development rather than a source of vulnerability. While the government should follow a more cautious borrowing policy, structural reforms in revenue collection, public expenditure, and project execution must be pursued simultaneously. Strengthening institutions to improve these areas is critical for easing debt repayment pressures and maintaining macroeconomic stability. External borrowing will remain important for development financing. However, its management will determine whether it becomes a growth enabler or a looming burden.

Dr Fahmida Khatun is executive director at the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD).

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments