Ranking race: Can’t live with them, can’t live without them

This is the time of the year when newspapers tell universities what they need to do. The butterflies of an influential magazine in the UK has fluttered their wings to air the news of who's who in the educational landscape. The centrifugal force of the wings flapping has created a storm in our local news outlets and newsfeed. A section of the local press cried havoc in a classic half-empty rhetoric, "No university from Bangladesh in the top 800 global rankings." The news, however, could have mentioned that there are two new entries from Bangladesh in the top 1,000 universities of the world, according to the Times Higher Education (THE) World Rankings 2024. Brac University (BracU) and Jahangirnagar University (JU) have joined their compatriots, the University of Dhaka (DU) and North South University (NSU).

THE has widened the net to incorporate 1,904 universities from 104 countries. Until 2011, before THE partnered with Thomson Reuters Foundation for data analysis, it published a coveted list of 200 universities under the old methodology. DU got featured on the list for the first time in 2016 in the 601-800 bracket. The university was pushed outside the top 1,000 circuit on the THE world ranking lists of 2018, 2020 and 2021. In 2022, DU returned to the club of 801-1000 universities. In 2023, it moved up the ladder to be placed in the 601-800 band, only to slip back to its present 801-1000 position.

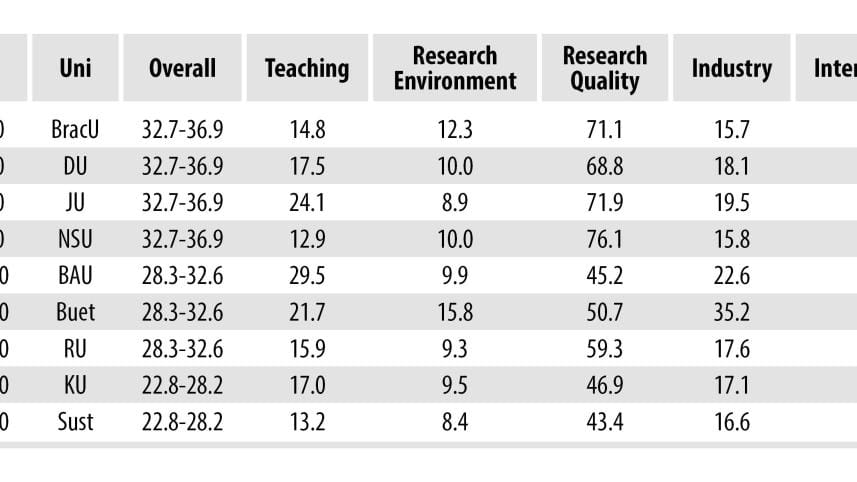

Last year, eyebrows were raised when a 30-year-young private university, NSU, breathed on the neck of the century-old DU in the 601-800 ring. DU is likely to feel more pressure with two new challengers. But it is encouraging to see that Bangladeshi universities are making strategic efforts to be on the world map. A total of 21 universities submitted data to be ranked by THE World Rankings; only nine made the final cuts. Bangladesh Agricultural University (BAU), Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (Buet) and Rajshahi University (RU) are in the 1001–1200 slots, while Khulna University (KU) and Shahjalal University of Science and Technology (Sust) are placed in the 1201-1500 slots.

As an academic administrator, I know how difficult it is to be on the list. University rankings are complex and multifaceted. The parameters through which the quality and performance of a university are measured are far from simple. To be successful, they require a combination of resource allocation, research output, academic perception, international collaboration, funding opportunities, quality of education, breaking the language barriers, and institutional policies. The process leads to a competition, often unhealthy, that has forced universities to join a "numbers game where administrators are incentivised to manipulate figures, game the system, and focus on parameters of dubious importance while paying scant attention to what happens in the classroom." One scandalous instance of manipulation became apparent when Columbia University was found guilty of doctoring data. From being the number one US university, Columbia was subsequently downgraded on the ranking list of News & World in 2022. Ranking agencies rely on the data submitted by the institutions and the research data available in the international repository.

While university rankings serve as crucial tools for students and parents to make informed choices before investing in their higher education, overemphasis on rankings may change institutional priorities and lead to a hollowing out of the educational experience for its stakeholders. At the same time, these supposedly well-intentioned pursuits of evaluating academic excellence through rankings may inadvertently create unhealthy competition.

So, I congratulate all the participating universities for their efforts. For THE World Rankings, there are three key criteria that institutions must meet to be considered for enlistment: teaching at the undergraduate level; at least 1,000 publications in the past five years and 150 each year in journals listed in Elsevier; and less than 80 percent research in one single subject. The second criterion acts as a gatekeeper, as the participating universities must build a research portfolio over a long period of time. Sadly, our universities were designed to be teaching institutions with a value system that did not necessarily match the ranking benchmarks with their heavy research orientation. Higher education in Bangladesh has been viewed as a public good that benefits the individual receiving it and their broader community in turn. A quick glance at the ranking metrics will tell you that many of the categories put our local universities in a disadvantageous position. The grades for institutional income and industry income are cases in point.

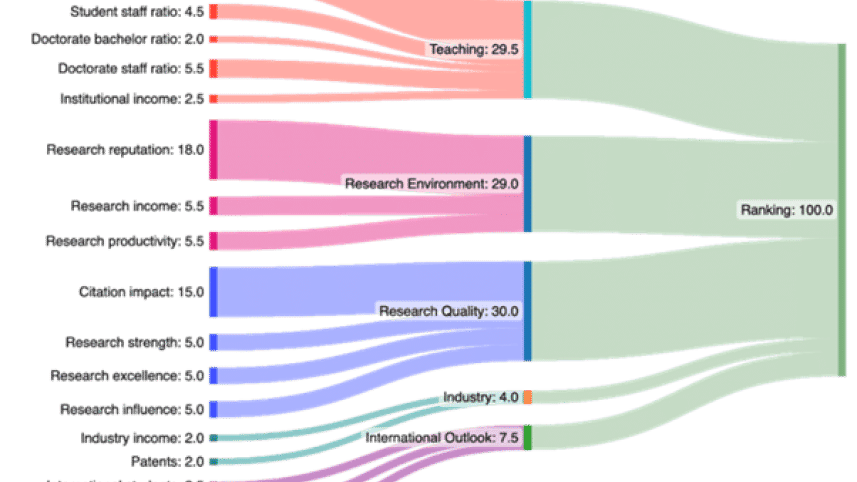

The four foundational pillars of this year's THE World Rankings include teaching (29.5 percent), research environment (29 percent), research quality (30 percent), industry (four percent), and international outlook (7.5 percent). There is 59 percent emphasis on research, which includes metrics on the citation impact and the income, reputation, productivity, strength, influence and excellence of research work. The dataset for this category comes from one digital repository: Elsevier. So our finest scholar, with his monograph written in Bangla over a 10-year period, may have no impact on the university's research health card prepared by THE.

In a blog featured on the THE website, David Matthews warns us of the digital monopoly, where these new big data bosses have their "tentacles everywhere, from the laboratory to the research grants office to academic personnel, which makes the switching costs potentially enormous." Universities are becoming slaves to these new corporate marketing ploys. While university rankings serve as crucial tools for students and parents to make informed choices before investing in their higher education, overemphasis on rankings may change institutional priorities and lead to a hollowing out of the educational experience for its stakeholders. At the same time, these supposedly well-intentioned pursuits of evaluating academic excellence through rankings may inadvertently create unhealthy competition. In this race, universities vie for higher positions on the leaderboard, marking frenzied attempts to outmanoeuvre their peers.

Dr Shamsad Mortuza is professor of English at Dhaka University.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments