Horrors of the Gaza genocide: Through a survivor’s eyes

"People care about us Palestinians in Gaza when we're killed, but they don't want to hear about the pain we are going through everyday, alive, as human beings."

Trigger Warning: The following content contains graphic details of violence, blood and death. Reader discretion is advised.

On April 5, 2024, Kamel Abu Amsha landed in Dhaka after 170 days of uncountable near-death experiences, back to "normal life." He does not know what to do with peace in Bangladesh. He appreciates that people in Bangladesh stand with Gaza, that they want the freedom of his people. But he doesn't know what to do with that either. He feels too often that the solidarity for Palestinian lives in Gaza, their real lives—of love, joy and grief—are reduced to a faceless number of casualties.

"No one really gets what happens there every day, especially in North Gaza, even if you see it on your phone. We lived many lives every day, and parts of us died everyday," he told me.

Bangladesh faces dangerous heat waves currently, but Kamel is beyond grateful that he has a fan and a room. But each night, in his bed in Faridpur, Kamel keeps waking up every thirty minutes, hearing thumping sounds of air raids and hallucinating tanks and bombs. His bed is more comfortable than all the cold, mucky floors, slick with gelatinous blood, of overcrowded refugee camps, and the blood-drenched hospital beds of injured patients, where he's slept over the past seven months. He was in the worst, most dangerous conditions he could've ever imagined, but he feels confused, as he finds himself missing even that "horrible life in Gaza," he told me.

He walks to class in Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical College (BSMMC) in Faridpur; his life is confined to his doctors' quarters, medical courses and mostly, to his phone, where every other day, he receives news that someone he knew, someone he loved, has been killed.

PART I: THE BEAUTIFUL DAYS

Kamel's father, Akram, 55, means everything to him. Akram ran a small store where he sold chicken, near their house in Beit Hanoun, Northern Gaza, just over 10 kilometres away from the barbed-wire border of Israel. Akram always encouraged Kamel to make something of himself, "to help people." Since he was young, Kamel had wanted to study in Al-Azhar University in Gaza and become a doctor. But the expenses were too high for his father. Akram felt ashamed that he couldn't provide for his son, that he'd failed his son. Kamel felt distraught seeing his father feel this way, so he applied to scholarship programmes for disadvantaged Palestinian students in foreign universities.

In 2019, he left Gaza for Bangladesh. It was immensely difficult for Kamel; his family of six brothers and one sister have always been tight-knit. They shared rooms in their three-storied house, and ate dinner together every single night. They celebrated Eid cherishing their Palestinian custom of eating Fasekh—a specialty dish of gray mullet freshly fished from the sea, and marinated for fourteen days, served with fried tomatoes. Kamel grew up close to his cousins too. Hasan, from his mom's side, was Kamel's age, and his best friend and confidant. They were inseparable. Kamel loved his little life in Gaza, even though the hope of liberation one day from the "open-air prison" always seemed too distant.

During his four years in Faridpur, Kamel missed everything about home. He watched The Pursuit of Happiness because it reminded him of his father's struggles and sacrifices to provide for Kamel and his siblings. Last year, on September 29, Kamel finally went back. "It had been too long," he told me, smiling.

He cannot articulate the feeling of seeing his father after thousands of days, when he got out of the taxi; both broke down, loudly. It was also his 24th birthday. They celebrated with a little cake that read, "Happy Birthday Dr Kamel." He felt embarrassed that they were "too proud" of him, he told me.

He excitedly opened his suitcase full of gifts the same night. He bought panjabis from Faridpur for everyone, even a mini-size one for his nephew who was still in his sister-in-law's womb. Over the next few days, his relatives came to visit him. He was reunited with his cousin Hasan, who told him he was planning on getting married soon. "Then you must do it quickly so I can attend while I'm here," Kamel had joked.

Then in an instant, life as he knew it, turned upside down. Hasan was killed in an airstrike in January, 2024. "I buried him," Kamel shared with me, shaking his head and reaching out for a tissue, as a welled up tear began trickling down his cheekbone. "Sorry," he said, rubbing his nose, "Remembering those beautiful days, that's what hurts the most."

PART II: A LITTLE LIFE IN CAMPS

On October 7, 2023, Kamel was sleeping, when he heard rockets and missiles barrage the sky. "Please not now," he thought to himself. He had lived through many flare-ups in Gaza, in 2006, 2008, 2011 and 2014. Even while he was in Faridpur, the Israeli army had attacked Gaza in 2021 and 2022. He had prayed that this month, this time, it would not happen again.

Soon, he heard the news: Hamas had carried out its biggest attack in Israel and Israel had declared war. The uncertainty of what would unfold reigned over his body. His family quietly locked themselves in house arrest; they hoped that it would pass soon like previous conflicts. But the bombs this time were far more destructive; at every thunderous explosion, his family was sure they were going to die. They hadn't heard from his elder brother, Emad, 28, who Kamel had met just a day before. Till today, they don't know whether he's alive or dead.

The Israeli army had ordered the residents to evacuate the north but Kamel's family refused to leave, because they knew the Israeli army would take it. On the 5th night of the war, as bombs exploded like a dance of murderous fireworks, his family knew there were no options anymore. His mother rushed to pack his medical textbooks. "Where will I study, let's go," he had said as they all vacated the house, leaving behind the life they had built in it, for 35 years.

They began searching for a safe place nearby and went to a school in Al-Falujah, which was turned into a refugee camp, crammed with thousands of displaced Gazans. His heavily pregnant sister-in-law was with them. They ate canned beans and corned beef, and showered every fifteen days. He doesn't want to remember the bathrooms, but the stench and visuals of mud mixed with faeces of children—who couldn't control themselves waiting in the long queues like the adults—is etched on his memory.

And every day, they experienced heavy bombing. Soon, the supply of food got thinner and thinner, as did the people. The Israeli bombs first targetted the vegetable market and food stores nearby, to start the cycle of starvation, Kamel recounts.

They chopped up wood to make fire as gas had run out. When wood also became scarce, Kamel's family had no options but to use his medical textbooks that his mother had taken, to make fire and cook some food to survive.

Oftentimes shrapnel, shells and stones from the bombs would spray onto their camp, and injure people next to him. Some died in the school. In just a week, the sight of people dying around him—he respectfully refers to everyone as martyrs—had become normal.

Kamel's family had one priority: the baby, who they had decided to name Akram after his father. Around the 15th day of war, as his sister-in-law's due date approached, Kamel went back to their house to retrieve the baby's clothes and diapers. Shells exploded from rooftops nearby. He quickly packed the baby's panjabi that he had bought in Bangladesh. The same day, once he returned to Al-Falujah, Kamel buried two of his cousins who had been killed in airstrikes.

At dawn, on 27 October, 2023, his sister-in-law's water broke. Nerves running high, as bombs pounded the northern strip, they managed—by a stroke of luck or fate—to take her to Kamal Adwan Hospital, which had an obstetrician facility, reaching around 4am. And like a miracle, baby Akram made it into the world. He had sepsis, but he was brought to the camp two hours after he was born, as there was no space in the hospital. Even as death engulfed the north of Gaza, they celebrated the birth of new life.

Then the rumours of the Israeli ground invasion became a reality.

PART III: TERROR EVERYWHERE

There were so many atrocities happening everyday that Kamel lost all notion of time. As a medical student, Kamel felt it was his duty to help. So, he began volunteering at the Indonesian Hospital in Beit Lahiya. It was a 45-minute walk from the Al-Falujah camp. He would work at the hospital for two days at a stretch, go back to see his family, and rotate again. He worked in the emergency room of the Indonesian Hospital for 40 days, then in Al-Ma'amadani Hospital for 30 days and Al-Shifa hospital for another 40 days. He had forgotten that he was, in fact, just a 24-year-old student, that he'd come to Gaza because he was stressed about exams.

In the Indonesian hospital, each day, every hour, they received more than 100 injured patients, screaming in pain. The hospital was a 140-bed facility and was used to treat 250 patients per day, after it was launched in 2016. Kamel witnessed families like his get shattered, and whole families wiped out. On the 40th day of war, he received a call that his closest friend, Ahmed Shabat, had been killed by an airstrike while trying to buy bread from a bakery. Kamel didn't have time to mourn him. Death of loved ones was now routine.

There's one incident at the hospital that he remembers every day before he goes to sleep. He was in the ICU, when a man carrying a nine month old fetus with an intact umbilical cord rushed to Kamel. The male fetus was dripping in blood—his skull was completely fractured and bits of feeble bones were sticking out. His mother was killed, the man cried. Kamel still does not know how, but he thinks her abdomen had been burst by tank bombs, and the fetus had fallen out on the ground, or been hit by a chunk of shrapnel. "Please save him, I don't want to lose him," the man cried.

But Kamel knew the fetus was already dead. He just could not get himself to tell the father. So, he said, "Okay I will do my best." Kamel wrapped the fetus in a large piece of white cloth and told the father that he couldn't save him. The father couldn't accept it, and kept begging him to do something. Kamel had nothing to say, and no time to console him. More injured people from the airstrike, mostly children, kept pouring into the hospital. He received ten cases of children with deep skin-peeled burns from phosphorous bombs—yellow sloughed tissue, Kamel described, squinting his eyes.

But he witnessed horrors outside the hospital too. One day, when Kamel was walking from the camp back to the Indonesian Hospital for duty, passing through a street on his regular route. Around three minutes after he had just crossed, he heard explosions of multiple rockets slamming in that direction. He sprinted and found refuge under a house. The street turned to smouldering ashes, splattered with blood; the hundreds of people walking behind him lay on the granite, lifeless. His father, whose angina and hypertension was getting worse, had run to the Indonesian Hospital when he heard about the massacre. Like a ragged silhouette, his father reached him. "He thought I was dead," Kamel recounted.

On the 45th day of the war, his family's fears about Kamel's life reached a devastating height. Around 2am, when Kamel was working in the Indonesian Hospital, he heard gunshots. The staff was shell-shocked, realising what was happening: a hospital siege. Kamel ran upstairs to the third floor with a group of hospital staff members. Through microphones, the Israeli army ordered people to leave, saying they will bomb the hospital. Unlike previous conflicts, the Israeli army in this war was not only from Israel, Kamel told me. "Some spoke really good English with accents. They spoke Dutch, French, Arabic and other languages," he described. "It was weird."

The Israeli army let guard dogs into the hospital as drones swirled by the windows, Kamel claims. The doctors and nurses refused to leave their critical patients behind. They stayed put for days, in a hostage situation, without any food or water. They heard the army torture critically ill and injured patients by beating them with wooden sticks. The military had claimed that Hamas soldiers were hiding there, Kamel told me. "If they were targeting only Hamas soldiers, then why did they attack and kill patients and torture them? Are we human beings or what?" He claimed, his eyes wide open.

The siege came to an end when an ambulance from the International Committee of Red Crescent arrived to take patients to the Al-Nasser Hospital in the South of Gaza. But Kamel would never abandon his family in the North. On his way out of the hospital, Kamel saw a lot of patients, lying dead with bullet marks, blood smeared on the cloth of hospital beds. He ran to the Al-Falujah camp where his family was waiting for him, terrified.

Huddled in the fragile safety of the camp, Kamel's family heard that a "truce" had been reached. They knew it would be a temporary respite as the army had not retreated from the streets of Gaza. Kamel, his uncle, and brothers returned home to Beit Hanoun, to find some food from the house.

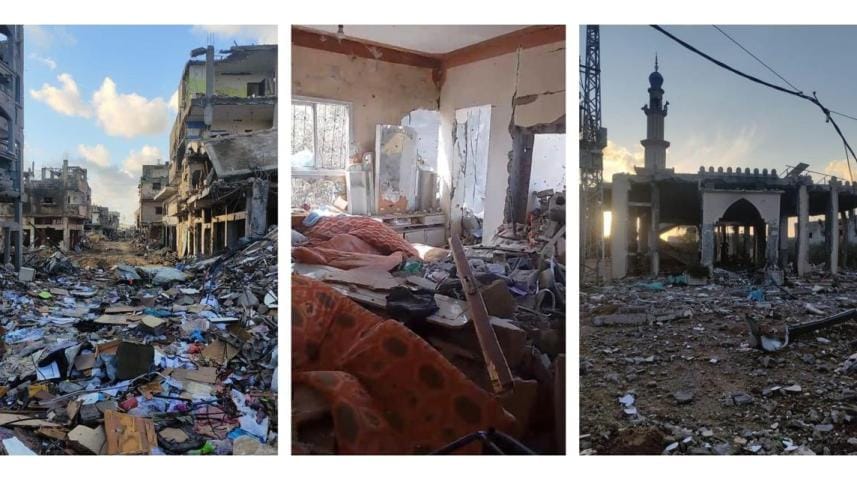

When they went, they saw that their house had already been bombed. The bowl of flour they'd left on the kitchen counter, was dusted with rubble. But they couldn't stay for long; drones began swarming the sky above like angry wasps. While returning, he saw more injured people on the streets, and that's when Kamel recalled that he left his backpack, in which he carried medical tools—dressings, antibiotics, painkillers—in the Indonesian Hospital. He went back to the hospital, which was now out of service. Before entering, he saw piles of decomposing bodies, partially hollow skeletons with open flesh, on the pavement. Stray animals, also dying in air raids and deprived of food, were eating the flesh off dead human bodies.

In the hours he would spend walking from place to place, Kamel would help civilians rescue injured people from under the rubble. He would help limbless people by carrying them to hospitals, and treat some with dressings on the spot to tamper bleeding.

Before the "truce" ended—Kamel claims there was no such thing as "truce"—he began volunteering at the partially functional Al-Ma'amadani Hospital, also known as Al-Ahli Arab Hospital, which suffered a massive blast in its garden-area on October 18—killing nearly 500 Palestinians. A month after Kamel joined, the Israeli army forced everyone in Al-Ma'amadani Hospital to evacuate, and Kamel witnessed injured patients, even in wheelchairs, killed by snipers when they made their way out of the hospital, as ordered.

"I don't know how they count the number of people killed, but I saw so many people killed in so many different horrible ways. So many human beings. I am pretty sure a lot of martyrs remain uncounted," he told me.

Kamel's only calm moments were at the refugee camp in Al-Falujah, which had become their home until December 1, 2023, when the Israeli army brought tanks, and laid siege. They threw smoke bombs—he doesn't know what chemicals are in these bombs—at the civilians and began shooting to force them to evacuate. It felt as though being a human being in Gaza—his home, where he had grown up—was now illegal.

PART IV: AN INCH OF LUCK

They walked for kilometres and found another camp, in an area, called "Zainab Alwazeer," between Jabalia in the North and Gaza City. On December 7, at exactly 8pm, the nightmare began again. The Israeli army began circling all the shelters in the area, and fired over 20 smoke bombs at civilians. Enormous fumes swallowed up the tiny room where Kamel's family was, which had no windows, and where almost a hundred people were stuffed. They managed to escape onto the streets which were also filled with the same clumps of smoke. Some people had collapsed, and died right there.

Kamel and his sister walked about 100 metres, when he started feeling terribly sick. He couldn't breathe anymore. It was at that point that Kamel gave up. He managed to tell his little sister, Kawsher, 17, to go find their father and walk with him. He fainted a few seconds after.

When he woke up, he had been carried to the pavement of another dusty street. He saw his father crying hysterically in front of him; Kawsher was shouting at the top of her lungs. He stood back on his feet, and they quickly shifted to another outdoor camp nearby, which was overflowing with displaced citizens. Wobbly and weak, Kamel saw five heavily injured people. One of them was a 13 or 14-year-old boy whose entire family had been killed. The boy had lost a lot of blood with a cut in his femoral artery in his thigh; he was about to die. Kamel had his medical backpack. He stitched the wound up, wrapped the area up in a tourniquet to stop further bleeding. He gave the boy saline and retreated to a jammed room, where his family was. It was especially cold that night; they did not have any blankets; they were wearing ripped t-shirts. They hugged each other to keep themselves warm while shivering like babies for eight hours.

The next morning, Kamel understood they needed to get some of their belongings, any bits of food or blankets that were left, in the first refugee camp in Al-Falujah. When he reached, he saw decomposed human bodies piled outside. He could recognise one of them. He wanted to bury the human beings, but if he dug out a grave, the Israeli military would be suspicious and shoot him.

When he entered the classroom where they used to stay, a sniper shot at him. It went right through the other side. He was saved by a few centimetres, or an inch, of luck. He hid in a corner and sat alone for hours. "For God's sake, what is this," he said, pausing when detailing the incident. Once night fell, he tiptoed out, unsure whether a sniper would kill him. He doesn't how or why he survived.

PART V: A GAME OF LIFE AND DEATH

The next day, his family was on the road again to find a safer place. They went to the UN relief agency, UNRWA centre, in the west of Gaza. The situation was much better there, with 300 staff members. They had food and breathing space; it felt like paradise. Kamel began working at the Al-Shifa hospital, which was a lot more crowded than the others. Though the hospital had suffered from two sieges, it was still functional at the time. Injured people, missing bits and pieces of their bodies, took shelter on the stairs, by the bathrooms. The smell of urine hunkered in the corridors. Kamel would treat patients during the days, and at night, he served as a consultant and prescribed medications to patients at the UNRWA medical spot.

Around 9pm, on January 31, 2024, when his mother was making rice, the Israeli military started hounding the area with tank bombs. There were schools around the UNRWA centre where people took refuge, and through the window Kamel and his family witnessed the army separating the men and women in two different lines, ordering them to get naked. Then they proceeded to arrest some of them while sparing others. He doesn't know the selection that precedes the arrests.

The next few hours, they waited in the anxiety of death. They knew the army would not pardon the UNRWA centre, because they did not pardon anything. The Israeli government has claimed that UNRWA relief workers have ties to Hamas and Islamic Jihad to justify their attacks. What was more threatening this time was that they didn't know where the Israeli army was hiding. Some people decided to escape from the doors on the west side. That's where they faced snipers. Five or six people were killed on the spot. People started screaming and running in different directions. Kamel and his family escaped through the east side, but there was carnage ahead. "Worse than any horror movie I had ever seen," Kamel described.

They walked forward in a line outside the UNRWA centre, and suddenly snipers began shooting at everyone like a brushfire. One human being passed, got shot by a sniper, and another passed and survived. It was a gamble between life and death. He saw pieces of brains, organs, bursting out into the air, on the ground, on him.

"There was a fight going on in my mind, that I shouldn't take this step, if I take it, I will die. But then I thought that if I don't take a step forward, then they will shoot me as well," he said. He ran, eyes closed. He passed. But he did not know the fate of his family. There was only a fifty-fifty probability for each person to survive. And he was one hundred percent sure that everyone would die.

When he saw his father crossing alive, Kamel started voluminously crying. "How many of them are dead, please tell me," he kept crying.

Everyone in his family made it out alive.

They knew they had been lucky, too lucky. It was going to run out soon. So, they went back home to Beit Hanoun, to die together.

Note: The Israeli government has claimed that workers of the UN relief agency, UNRWA have ties to Hamas and Islamic Jihad to justify the attacks. Till today, the government has not yet provide substantial evidence supporting its claims.

PART VI: ANIMAL FOOD AND THE LIST

It was February 1. The town where he grew up was unrecognisable. It was grayer than the insides of the mullet they cooked during Eid. Their house was bombed for the second time, and only the entrance of it remained. They stayed there for a night in search of food. They walked around during the day, as no one was allowed to get out after 5pm. Night fell, and there were airstrikes. One day, as he walked around in search of food, Kamel found the home of his 10th grade Arabic teacher, Youssef, which had been struck the night before. His teacher was screaming under the rubble. Kamel and his family tried to pry him loose from under the debris for hours. He was dead by the time they recovered him.

They walked over to the periphery of Northern Gaza, where his aunt lived. Her house was not fully bombed; a room was still inhabitable for the ten members of his family. They went near the Erez crossing, barricaded within a concrete wall and a heavily-fenced Israeli border. Anyone who steps within 1km of this barrier is in danger of being shot by the Israeli army. As he and his family walked across, the glimpses of the hinterland across the border made him crumble inside. He could see life: tall buildings, glass windows, and cars in Israel.

On his side of the border, they went 15 days without any food, drinking salt water from the beach, or from dirty tube wells. They picked grass from the wasteland and swallowed it. His family was in hypoglycemic shock, their pulses were weak. They would writhe and grimace in hunger. To treat hypoglycemic shocks, Kamel needed injections which he did not have. Each night they went to sleep, Kamel accepted that the prophesied doom was near: maybe the next day, or in a few hours, he would wake up and have to bury his brother, mother or father, if they didn't wake up. Or they would have to bury him.

Then his brother heard that some people were serving "food" somewhere nearby in a cart. It was animal feed, but they were so ecstatic, Kamel told me in a matter-of-fact way. They did whatever they could to survive.

On March 24, Kamel's uncle came and woke him up. "Your name has been published on the list! Get up!" he shouted.

"What list? What list?" He'd responded.

That's when Kamel remembered, that around the beginning of the war, he had registered in a few student organisations which were helping students studying abroad to escape Gaza. The organisation would pay $5,000 to let him cross the border—that's how much it cost to cross Rafah to Egypt. (He's never met anyone in the organisation, he doesn't know how they pay, or who they pay to). He felt an electric shock through his chest.

"No," he told his uncle. "I'm not going." He refused to leave. Kamel and his family were starving, and he knew what his family was facing. They are not students, so they won't be allowed to leave with him. Kamel and his family didn't have any money let alone the amount needed to cross the borders.

"We know our fate, but you have a different fate. Go finish your journey," his father had said, "Go back, go become a doctor."

He was crushed, broken, but he knew he had to go. Kamel departed, knowing it could be the last time he sees them. But he doesn't want to think like that. "They're my life," he told me.

PART VII: CROSSING DEADLY BORDERS

Kamel started off with the backpack he carried around. The only memory he took with him was the tape on his phone charger that his sister had put to mark theirs, when they were in the camps. The Israeli army was destroying the Al-Shifa hospital when he was coming back, and he had to cross Al-Rashid street dividing the North and South of Gaza. When he reached, he saw that the army had set up a temporary border between North and South Gaza with large shipping containers. He was frozen; how would he pass? He was alone on the street, as bombs exploded nearby. He then saw a girl and two boys, who were also students like him, studying in Algeria.

The girl had a heavy bag she was struggling with, so Kamel carried it. The boys entered the container before Kamel, and there was a camera inside. Outside of the container, there were dozens of soldiers, with tanks and jeeps. When the boys crossed over, the Israeli soldiers caught them. Kamel saw the soldiers force the two boys to take their clothes off, take their bags, and arrest them. The girl began to cry. Kamel was sure, it's over, but he whispered to her, "We have to pretend that we are a family, like husband and wife. We can pass."

They held hands and walked, looking straight ahead. The army didn't call them. They passed.

They walked kilometres and kilometres, as night settled, reaching the South in Nuseirat. The girl went to see her relatives, he does not know her fate.

Kamel stayed at his uncle's place for two nights in the South, which was like a "different country," he told me. "The north, where I'm from, and where my family is now—it is a complete ghost-town. There's still some life in the South."

He left the South to Rafah, where an imaginable number of people were clustered. "If Israel attacks and bombs Rafah the way they bombed the north, it will be a genocide in one day," Kamel told me, as we discussed Israel's current decision to advance in Rafah.

He arrived at the "6th of October city" in Egypt, and called his uncle, who had moved to Cairo 25 years ago. His uncle took him to his house. "It was a complete fantasy," Kamel said. It felt sickening too, to see life. "Why does everyone get to have a life but we don't? Why?"

In Cairo, Kamel showered and informed his college in Faridpur that he had reached Cairo, and they booked a flight for him on Gulf Air. He also managed to call his family, who had limited internet. They were alive too. "It felt like a liberation from war at the time, but it wasn't," he said.

PART VIII: DYING IS BETTER THAN THIS LIFE

Kamel has lost over 20 family members and eight friends, till date. At least eight of them are under the rubble and have not been recovered or buried. Since returning to Bangladesh, he has experienced severe trauma shocks, while still continuing to study for his professional medical exams. When was admitted to the Intensive Care Unit, for cardiac complications, he felt guilty and blamed himself for not being able to study, because, "my father gave me a big mission, to become a doctor," he expressed. He cannot eat because he feels guilt that his family cannot eat what he can. He feels guilty that he's safe.

Kamel's immediate family is still alive—except his brother Emad—as of May 2, 2024. They've faced three forced evacuations since he left. Once he hears that there's been a bombing in Beit Hanoun, he stays up all night worried for his family, calls journalists and everyone he knows in Gaza.

"It's another prison, and punishment, living like this, leaving them there, seeing with my own eyes where I've left them. Dying is better than this life," Kamel told me, repeatedly, over the past three weeks.

"Oh, how I wish I could bring them here in Bangladesh," Kamel told me, sighing.

The video account of the story is available here on Star Multimedia.

Ramisa Rob is Geopolitical Insights editor at The Daily Star.

Do you have an opinion on the issues raised in this article? If you would like to submit a response of up to 300 words by email to be considered for publication in our letters section, please send an email to ramisa@thedailystar.net or see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments