FIGHTING POVERTY

When it comes to the biggest challenges facing Bangladesh, surely poverty is one of the most crucial. And there is still much work to be done.

Despite cutting the rate of extreme poverty from 34 percent in 2000 to just 13 percent today, 20 million Bangladeshis still live in conditions considered to be ultra poor. Living on less than Tk. 43 per day can be immensely difficult, and for some, it can create a trap that's almost impossible to escape.

The ultra poor generally do not own land and are caught in the low-wage activities of day labourers. They are on the brink of subsistence. And when you are struggling just to maintain your level of subsistence today, you do not have the luxury of worrying too much about—or saving for—tomorrow.

The Bangladeshi government recently committed itself to pulling six million more people out of extreme poverty by 2020. Similarly, one of the United Nations' development targets for theyear 2030, the Sustainable Development Goals, is to eradicate extreme poverty entirely. Either goal would take a lot of work. How do we fight extreme poverty in the most effective way?

Our project, Bangladesh Priorities,examines a range of different possibilities for the country. Two of our economists, Munshi Sulaimanof BRAC International and Farzana Misha of Erasmus University Rotterdam, have examined three of the most important ways to tackle poverty in Bangladesh.

In recent years, cash transfers have become quite popular in countries such as Kenya and Uganda, and this was the first method our economists examined. Such programmes involve a one-time transfer to recipients, often micro-entrepreneurs, with no conditions on how the money can be used.

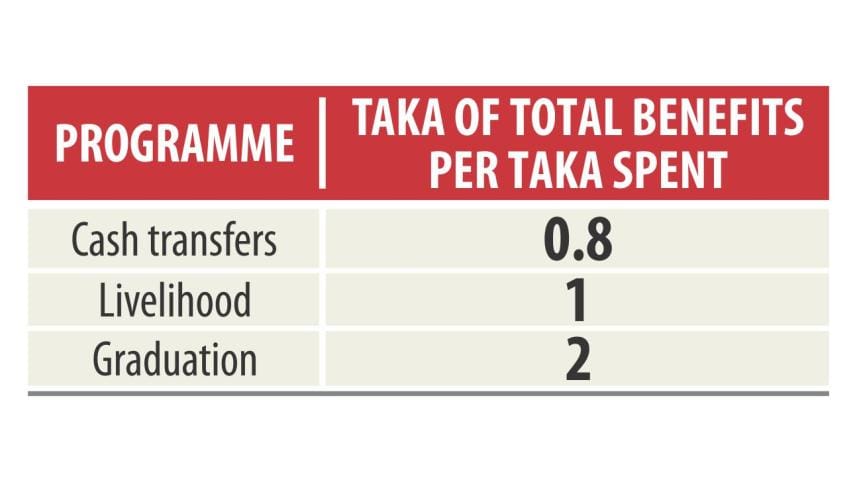

Why no-condition transfers? It turns out that much academic research shows that this is the most efficient method, which is one reason it has become so popular. The cash transfers we studied, however, which cost Tk18,096 (the paper reports per-household costs in USD only. I have converted this figure and all others in this op-ed using the rate: 1 USD = Tk. 78) per recipient household, did just Tk. 80 of good for every Tk. 100 spent.

One reason they weren't effective relative to other strategies is that the impacts diminished over time—a one-time stipend for someone in extreme poverty may help for a little while, but the effect is fleeting.

The second strategy focuses what most poverty-alleviation strategies have traditionally done: give people a livelihood "boost," so that they can prosper on their own. So-called"livelihood programmes" might give agronomic training and growing inputs such as improved seed to farmers, for example.

Some of the livelihood interventions our researchers studied were more promising than others, and the costs for one such programme were cheap—less than Tk. 7,800 per household. But the return on spending devoted to these efforts was merely one-to-one.

Another way out of poverty, and the most promising of the three we examined, is what is called graduation. It involves helping recipients through a variety of methods and over a particular time sequence.

In graduation programmes, participants first receive a small gift of cash or food, which eases the stress of daily survival and allows them to start saving. After that, they receive an asset, maybe a cow or a goat, along with basic financial and technical education. This component often involves animal-husbandry training delivered by a veterinarian. Many graduation programmes also provide healthcare support so that participants will not be forced to sell assets in the event of an emergency. Finally, participants get a confidence boost through social training - an important factor for escaping poverty that is often overlooked.

The assistance in the form of money, assets, and financial and social support allows participants to "graduate" out of extreme poverty over a set timeframe.

Our analysis shows that the cost of such a programme would be relatively expensive, approximately Tk. 23,400 per household. But the benefits would be substantial too. Graduation programmes would increase recipients' incomes by at least one-third. And it's likely that household benefits are somewhat understated, because the analysis has only estimated the income benefit but not the improved nutrition status of children.

In total, each taka spent on graduation programmes in Bangladesh could do Tk. 2 of social good, allowing participants to save for the future and, ultimately, escape extreme poverty. Much of the gains come from beneficiaries shifting occupations, progressing out of casual day labour and into self-employment. And importantly, we found evidence that the positive graduation effects can last for years after the programmes end, meaning that participants have the potential to pull themselves out of poverty for the long term.

This is a respectable return when it comes to helping the ultra poor. Our experts believe that there should be more study of the long-term impacts of livelihood and cash transfer programmes in Bangladesh. But based on our research, graduation seems the most promising of these three strategies.

In forthcoming articles, Bangladesh Priorities will look at what else we can do with foreign and national development money. These poverty policies are only three of 78 policies that the country could focus on. What do you think? Are these some of the best investments for Bangladesh? Let your voice be heard on facebook.com/dailystarnews. Let's start the conversation about where Bangladesh can do the most good.

The writer is president of the Copenhagen Consensus Center, ranking the smartest solutions to the world's biggest problems by cost-benefit. He was ranked one of the world's 100 most influential people by Time magazine.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments