How will artificial intelligence transform the labour market?

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is expected to pose the biggest disruption to global labour markets since the industrial revolution in the 19th century. The speed and scope of this unprecedented disruption will not be felt equally across industries, and nations. Bangladesh, a developing economy, will likely undergo a unique labour market transformation. Bangladesh’s job market remains largely informal, routine-task dominated, and credential-biased—rendering workers particularly susceptible to AI-powered automation. This poses a seemingly insurmountable risk for the two million Bangladeshis entering the labour market annually, including more than six lakh university graduates. Contemporary AI and robotic technologies are unable to undertake dextrous work rendering tenuous respite to vocational and technical jobs.

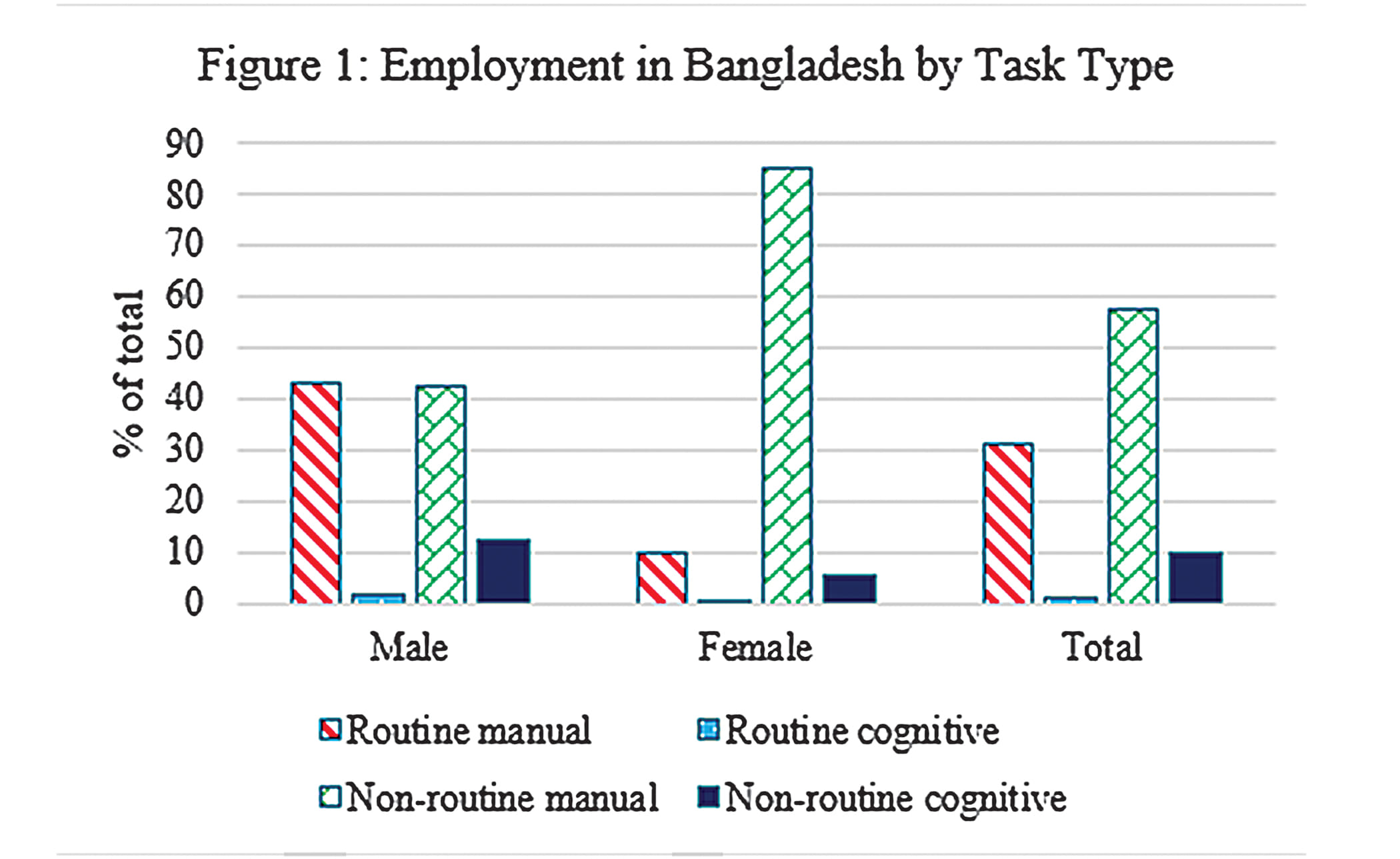

The skills mismatch between Bangladesh’s education system and labour market is widely highlighted in the nation’s public discourse. The rote-based education system prepares students for general repetitive tasks (Figure 1)—i.e., garments production line or customer service. AI and robotics can easily replace, and perhaps supersede, humans in these tasks. Bangladesh’s labour force is largely unprepared for complex and creative tasks in emerging professions at home and abroad. This has culminated in grade- and credential-inflated Bangladeshi ‘white-collar’ workers who remain inadequately prepared for many in-demand skills such as creative and professional content creation, design, data analysis, computer programming, AI prompt writing, inter alia.

Vocational and technical training may also help the aspirant migrant workers land overseas roles that are managerial, more secure, and well-paid. Photo: Prabir Das

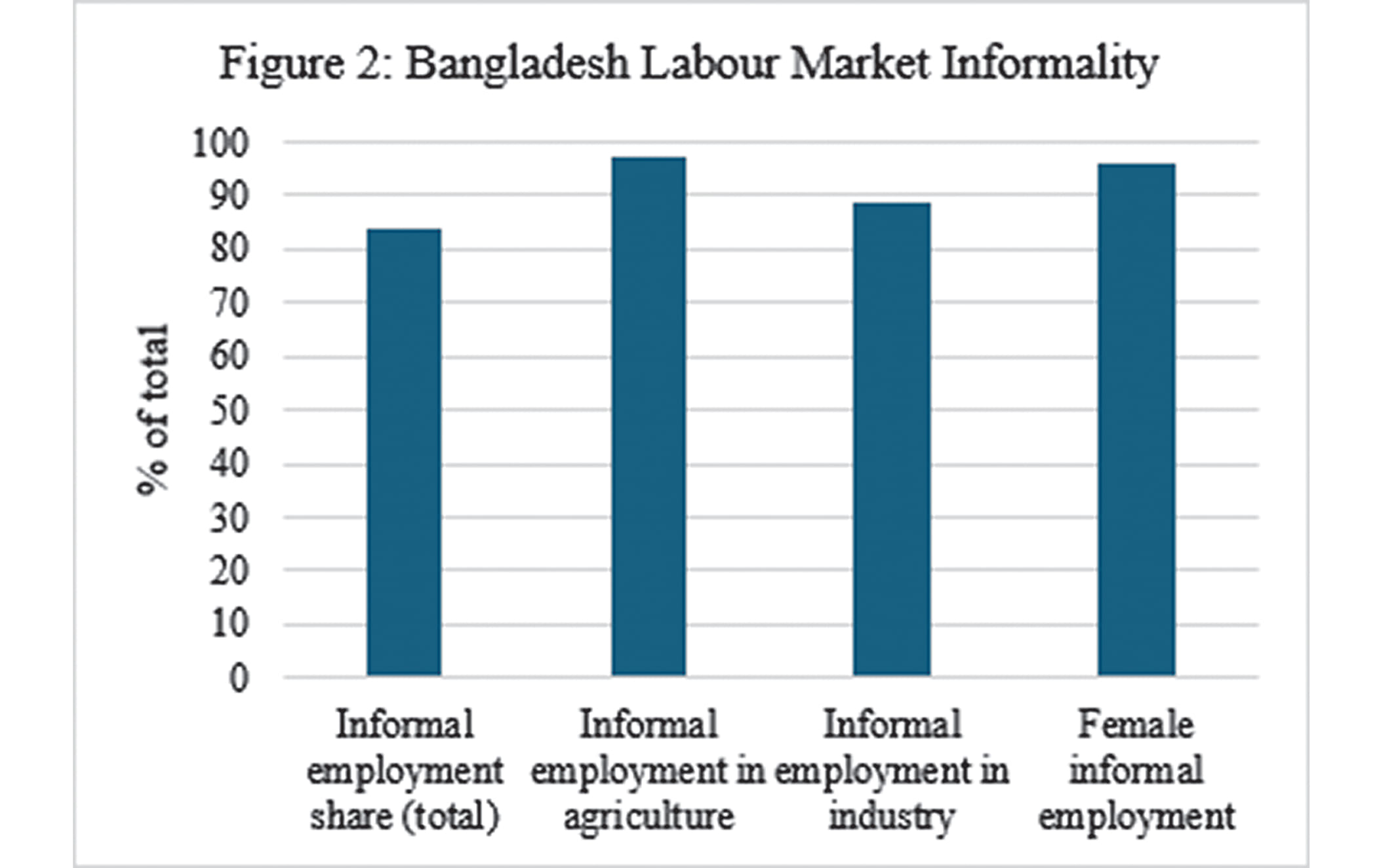

Bangladesh’s labour is overwhelmingly informal (Figure 2)—with impromptu, uncompetitive hiring/firing and no employer involvement in workers’ skill development.Employees and employersplace their trust on blind loyalty instead of upskilling and re-skilling.This creates a perplexing scenario where entry-level jobs erode due to automation and postponed hiring while firing remains minimal. This phenomenon, however, is prevalent not only in Bangladeshbut alsoacross much of the developed world. The ‘informality’ of Bangladeshi jobs makes workers more vulnerable, as employers may replace them for intermittent AI service subscriptions. Moreover, inequality is expected to worsen since entry- and mid-level roles, especially informal ones, are ‘hollowed out’ by AI.

The solution to this doomsday scenario is a structural transformation of how we educate our workers. Instead of banning AI from classrooms, students need to learn to use AI to their advantage. AI can help our students improve and develop their creativity, data analysis, and programming skills.In class, I often present the following perhaps overly optimistic and simplistic outlook for an AI-powered future:

Imagine a 2050 Facebook entrepreneur selling designer clothes—popularly known as ‘api’s’ or ‘sisters.’ During a live stream, she takes an order, designs a unique dress, and manufactures it in real time using AI prompt-writing and 3D printing, and delivers it within hours via AI-powered autonomous drones.

Such a scenario may not be far-fetched, as similar job roles and AI functionalities exist under current technologies. The key is to train these ‘api’s’ and create an enabling environment for AI to complement her creativity.

To date, Bangladesh’s policymakers, industry leaders, and educators placed limited emphasis on envisioning or planning for such a fully integrated future. Contrary to this doom and gloom, professions requiring vocational or technical skills appear relatively resilient to AI takeover for now. This is because contemporary AI systems are often centred around large language models which are suited to replacing desk-based routine tasks. In contrast, the latest automation and robotic technologies lack dexterity and adaptability needed to undertake non-routine manual work such as automobile repair, construction, cooking, and plumbing. These jobs also require on-premises diagnosis and problem-solving, decision-making, experience and intuition, and human interactions. AI-powered automation may perform some individual tasks more efficiently than human workers. However, AI is incapable of situational judgment that requires a holistic combination of all, or most, of the above tasks.

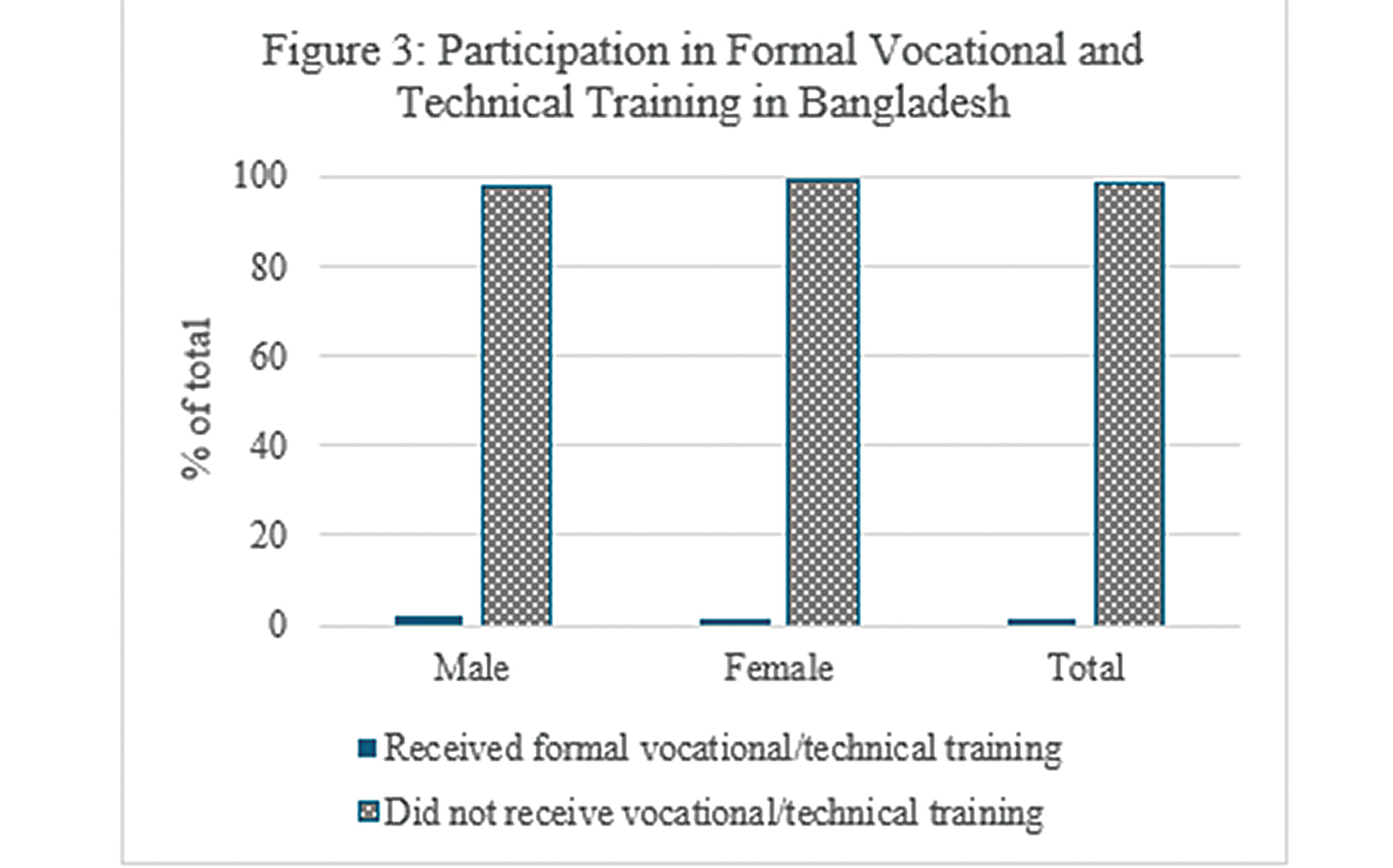

This represents a ray of hope for Bangladeshi workers. The country enjoys a demographic dividend, with some 4 in 10 Bangladeshis are under the age of 25. Yet, the economy is incapable of generating sufficient well-paid ‘white-collar’ jobs for the two million or so new jobseekers entering the labour market. Consequently, many are either unemployed or underemployed, with reports of workers with postgraduate qualifications filling menial roles. Here, vocational and technical skills can assist these workers reach their earnings potential and avoid getting replaced by AI and automation. Vocational and technical training may also help the aspirant migrant workers land overseas roles that are managerial, more secure, and well-paid. As such, ‘blue-collar’ skills can further boost Bangladesh’s remittances receipts. However, participation in formal vocation land technical training and work in Bangladeshis lacklustre ((2%; Figure 3), due to unfavourable societal attitudes, insufficient and underfunded formal training as well as institutional support.

Bangladesh’s labour market economics also presents an apparent reprieve from worrisome technological unemployment. Bangladesh has developed little or no indigenous AI technologies and is almost entirely import-dependant. Imported AI-powered automation remains expensive and, against the backdrop of abundant cheap labour, remains economically untenable considering the costs and benefits—especially for manual- and service-based roles. This scenario presents a case for AI-assisted productivity gain rather than AI replacement of jobs, especially in low- and middle-income economies like Bangladesh.

AI-powered automation is expected to aggravate gender inequality, as more women languish in automatable roles. This is in part due to societal barriers women face while accessing vocational training and technical jobs, which often require travel and after-hours work.

In conclusion, AI will disrupt Bangladesh’s labour market, akin to that in other countries. AI-powered automation—a once-in-a-lifetime disruption—poses substantial risks and opportunities to Bangladesh’s workers and the economy. Yet there is a lack of readiness among the country’s policymakers, education system, workers, and business community. It is important to develop a cohesive, competitive, democratic, and forward-looking strategy to prepare our labour and industry to implement AI to their advantage—analyse data, develop robust systems, and formulate creative solutions. If executed properly, AI-powered automation could help leapfrog Bangladesh’s development trajectory and improve citizens’ quality of life.

On a final note, I love writing—and I’d like to think AI-powered automation won’t take my job… yet.

Source: 2023 & 2024 Labour Force Surveys, Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics.

Muhammad Shafiullah, PhD, is an Economics Professor at BRAC University. He teaches international macroeconomics and data science (econometrics) at the under- and post-graduate levels, respectively. He remains interested in economic research on the environmental and environment, finance, and tourism and transportation. Dr Shafiullah can be reached by email at muhammad.shafiullah@bracu.ac.bd.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments