Law Analysis / Our inherently anti-poor vagrancy laws

16 December 2025, 18:00 PM

Law & Our Rights

Law Vision / Safeguarding novel designs in business

10 March 2025, 18:00 PM

Bots

Law and Technology / Technological advances and the right to freedom of thought: The liminal space

10 March 2025, 18:00 PM

Bots

Women and Law / Observing International Women’s Day

10 March 2025, 18:00 PM

Bots

Constitutional Law / A Powerless Senate? Rethinking Bangladesh’s Proposed Bicameralism

27 February 2025, 18:00 PM

Bots

Year-end Law Review / Reviewing the laws enacted in 2024

9 January 2025, 18:00 PM

Bots

Law Letter / Ensuring fair trials in Bangladesh

9 January 2025, 18:00 PM

Bots

Law Review / Revisiting the Draft Personal Data Protection Act 2023

19 December 2024, 18:00 PM

Bots

Laws of War / Understanding the Syrian Armed Conflict

19 December 2024, 18:00 PM

Bots

Gender and Law / Gender bias entrenched in our legislation

12 December 2024, 18:00 PM

Bots

Our inherently anti-poor vagrancy laws

During the colonial times, vagrancy laws were widely enacted in many European colonies, including the British Raj. In the erstwhile Bengal, the Raj enacted the Vagrancy Act, 1943 (Bengal Act), which specifically dealt with the issue of begging as an issue of vagrancy. I

16 December 2025, 18:00 PM

Why the Arbitration Act 2001 is not exhaustive

Arbitration has emerged as the pre-eminent mode of dispute resolution in domestic and international trade. Its absence could jeopardise the

22 December 2022, 18:00 PM

The Evidence (Amendment) Bill 2022: An appraisal

On August 31, 2022, the Evidence (Amendment) Bill was introduced before the parliament. This Bill will be an Act only after completing some legislative procedures.

30 September 2022, 18:00 PM

Reviewing the New Territorial Waters and Maritime Zones Act

The new Act seeks to amend the Territorial Waters and Maritime Zones Act 1974. The provisions of the 1974 Act were not coherent with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and were proposed to be amended since the UNCLOS 1982 entered into force later.

28 January 2022, 18:00 PM

Concerns over the proposed personal data protection bill

It has come to light through print and electronic media that the Government of Bangladesh has recently prepared a draft bill on the matter of personal data protection. Some very pertinent issues regarding the bill are set out below.

20 September 2021, 18:00 PM

Why the new ‘Digital Commerce Operation Guidelines’ needs major revisions?

In response to the growing impact of digital platforms on the country’s current economic successes and the challenges, the Ministry of Commerce enacted ‘Digital Commerce Operational Guidelines’ (hereinafter the guidelines) on July 4 this year.

2 August 2021, 18:00 PM

An overview of the Digital Commerce Operation Guidelines 2021

On 4 July, 2021 the Ministry of Commerce issued the Digital Commerce Operation Guidelines, 2021 pursuant to the National Digital Commerce Policy, 2018 (as amended in 2020) with the aim of ensuring transparency and accountability in the digital commerce sector, creating employment opportunities, ensuring the rights of the consumers and increasing the reliance on digital commerce by bringing about a regulatory framework, and creating a competitive market that provides opportunities for entrepreneurs.

12 July 2021, 18:00 PM

Marks to be Registered as Trademarks in Bangladesh

The importance of protecting Intellectual Property (hereinafter “IP”) rights is evidently unquestionable. In this era, the psychology of a consumer is to find out which company’s product is appropriate for him and the consumer usually does some market research in this regard.

5 July 2021, 18:00 PM

The laws relating to communicable diseases

In light of the current pandemic caused by COVID-19, it is important to review the existing legal provisions that outline the powers and duties of the Government to mitigate and prevent further spread of infectious diseases.

13 April 2020, 18:00 PM

Legal approaches to curb air pollution

The air quality of Dhaka has been “unhealthy” and “extremely unhealthy” for an increased duration in recent years, says an analysis of Air Quality Index data, monitored by the Department of Environment under its Clean Air and Sustainable Environment (CASE) project.

11 November 2019, 18:00 PM

The chronicle of gambling law: A legal analysis

Of so many queries that the recent drive against the casino by the law enforcing agencies put before the citizen of the courtly, one that comes out on top and perplexes us the most is – ‘are running and playing casino legal in Bangladesh?’.

14 October 2019, 18:00 PM

The importance of forensic evidence in our justice system

With the advent of time, the commission of crimes is becoming more sophisticated, critical, digital and organised. The pattern of committing crimes is changing with the changes of science and technology.

10 June 2019, 18:00 PM

Legal framework for workplace safety

Workplace health and safety conditions in Bangladesh has seen steady improvements since the disastrous Rana Plaza incident which

29 April 2019, 18:00 PM

Outside the scope of labour law

Section 2 of Bangladesh's Labour Act 2006 identifies certain institutions that would not fall within the purview of this law. The list

1 April 2019, 18:00 PM

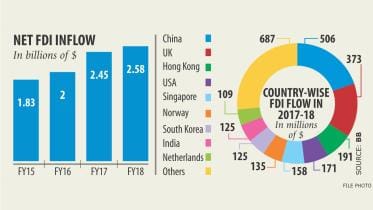

MAKING BANGLADESH AN ATTRACTIVE FDI DESTINATION : Challenges and options

FDIs have two competing interests: economic development for host states and profit maximisation for foreign investors. It is the lure

25 February 2019, 18:00 PM

Is punitive action enough to prevent abuse of drug?

Although Bangladesh is not a drug producing country, in terms of geographical location, it is juxtaposed between the golden and

4 February 2019, 18:00 PM

How far does it protect our privacy?

The Digital Security Act, 2018 (“DSA”), which came into force on October 8, 2018, was enacted to ensure digital security and to

7 January 2019, 18:00 PM

THE NIKO ARBITRATION Lessons for Bangladesh

The domestic trial of the Niko graft allegations has been continuing for quite some years, now reaching at the apex court in Bangladesh.

19 November 2018, 18:00 PM

Online freedom of expression under threat?

The Digital Security Act (DSA) 2018 aims to ensure digital security by punishing offences committed through digital media.

1 October 2018, 18:00 PM

Analysing the draft Bangladesh Labour (Amendment) Act 2018

The draft of Bangladesh Labour (Amendment) Act, 2018 aims to make labour law worker-friendly while regulating the conduct of workers and owners in compliance with the standards of International Labour Organization (ILO).

24 September 2018, 18:00 PM