Serving time even after amnesty

An elderly man has been rotting in prison for nine years even after getting presidential general amnesty.

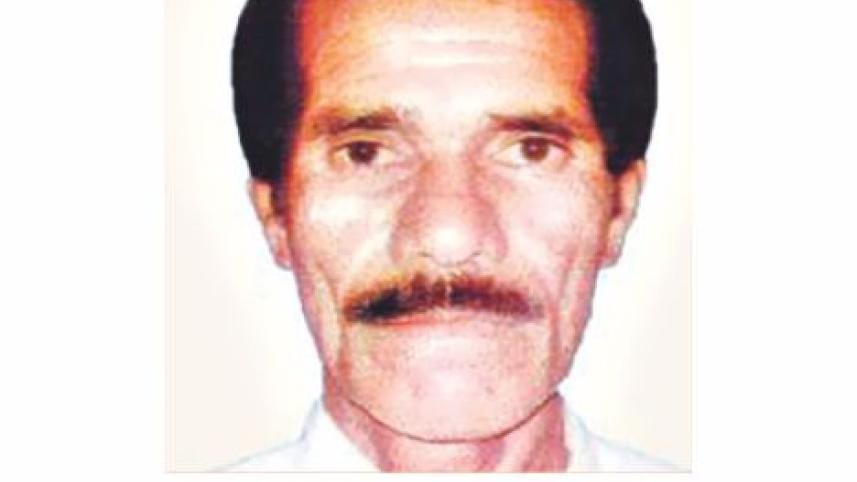

It all began three decades ago for Ajmat Ali, now 70. On June 7, 1987, he was made an accused in a murder case, along with several others from his Pakhimara village in Jamalpur's Sharishabari upazila.

With no other income earner in the hard-pressed family, Ajmat, then a schoolteacher, could not afford a lawyer. So, while almost all other accused walked out on bail one by one, Ajmat remained in jail.

Subsequently, a Jamalpur court sentenced him to life on March 8, 1989, documents show.

He appealed against his conviction before the High Court Division of the Supreme Court.

Meantime, while the appeal was still pending, he was freed, like many others, from jail in 1996 under the presidential amnesty.

The amnesty was granted in line with an order issued on January 14, 1991, in the name of the then acting president Justice Shahabuddin Ahmed. In this order, the life sentence was reduced to 20 years from 30 years. The order also allowed prisoners to walk out of jail upon serving half of their term.

So Ajmat was freed on August 21, 1996, on completion of half his 20-year term. Later in March 2005, the HC granted his appeal against the lower court verdict and acquitted him of the murder charges on grounds that the prosecution failed to prove his involvement beyond reasonable doubt, documents show.

But his plight was far from over. In 2006, the government challenged the HC Division verdict with the Appellate Division of the SC, which ordered his arrest in 2008.

Ajmat's life as a prisoner began again in October 2009 after police arrested him and produced him before a Jamalpur court, which sent him to the same Jamalpur jail.

Court sources said that during the appeal hearings in the Appellate Division, there was no lawyer to represent Ajmat. So the apex court could not know that he was freed years ago under a general amnesty.

In August 2010, the Appellate Division scrapped the HC judgment and upheld the lower court verdict, saying the HC was wrong in its decision.

WHO TO BLAME?

Ajmat's family refused to give up and chose to fight on. But what they experienced in the process once again exposed how justice-seekers can suffer even as their lives slip away.

They went to one lawyer after another, borrowing money from neighbours and relatives, taking loans and selling anything they could to pay for their pursuit of justice.

Finally, they managed to find one lawyer, Jayanta Kumar Dev, who made an unusual move. In January 2012, he wrote to the very District and Sessions Judge's court that had originally sentenced Ajmat to life.

In that application, the counsel detailed everything that had happened since Ajmat first landed in jail -- his conviction, the presidential pardon and the verdicts by both the SC divisions. The lawyer also sought the district court's intervention to have Ajmat freed.

Judge Malik Abdullah Al-Amin then wrote to the Supreme Court Registrar on March 25 the same year, seeking advice.

More than a year later on March 31, 2013, the SC authorities responded, instructing the Jamalpur court to take steps in line with the Appellate Division judgment and other relevant rules.

Signed by the then SC Deputy Registrar Ishak Mia, the letter made no mention about the mercy granted to Ajmat, who is still in jail.

His family is now seeking support from the Supreme Court Legal Aid office, which is preparing to file a petition for review of the Appellate Division verdict.

Asked who is to blame for Ajmat's predicament, SC Registrar Md Golam Rabbani yesterday said he needed to see all the relevant papers before making any comment.

Three other officials at his office, all of whom spoke on condition of anonymity, said that in case of a general amnesty there was no bar for the apex court to go ahead with the appeal proceedings.

Such an amnesty would not even have any impact on the verdict of the High Court Division and the Appellate Division, they added.

About Ajmat's release, they said it was for the prison authorities to decide in line with the Jail Code.

Jamalpur Jail Superintendent Mokhlesur Rahman declined to comment.

Supreme Court lawyer Khurshid Alam Khan agreed that there was no legal bar to proceed with the appeals in cases like Ajmat's. But the state had a responsibility to inform the apex court about the amnesty.

“Had the apex court known about this, it might have considered the matter before pronouncing the verdict,” he added.

While officials are caught up in the legal tangle, Ajmat's family are going through the worst kind of emotional turmoil -- the kind where hope is given for a moment but is taken away again.

“I don't understand why he has been taken in again after the presidential mercy. We have spent our lives without him,” said Beauty Akhter, Ajmat's eldest daughter.

[Our Jamalpur Correspondent ABM Aminul Islam contributed to this report]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments