Living on Death Row: A voice for the wronged and forgotten

Sitting in the comfort of our homes, sipping tea, we often forget the unseen injustices that unfold every day. But imagine, for a moment, that the warmth of that cup fades away. The soft bed is replaced by a cold, hard floor. The familiar room becomes a six-by-eight-foot cell shared with seven others. The thought alone is unsettling.

In Bangladesh, countless individuals face such realities — thrown into condemned cells after being accused of crimes they may not have committed. Some are executed, others die of illness, and a few are eventually released. But even for those who walk free, is it truly freedom? Social death lingers. The whispers, the suspicion, and the stigma follow them everywhere.

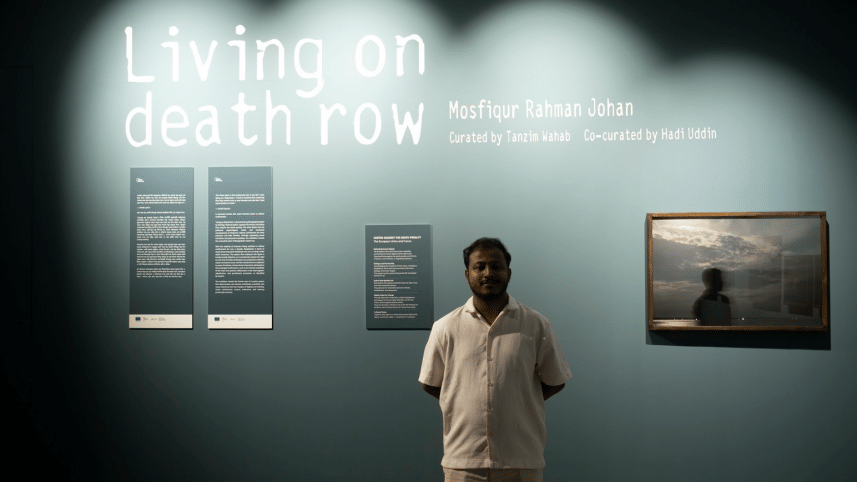

These are the questions that photographer Mostifqur Rahman Johan confronts in his exhibition Living on Death Row, curated by Tanzim Wahab and co-curated by Hadi Uddin. The exhibition, hosted at Drik Gallery, portrays the stories of 12 individuals who spent years in condemned cells before finally being released.

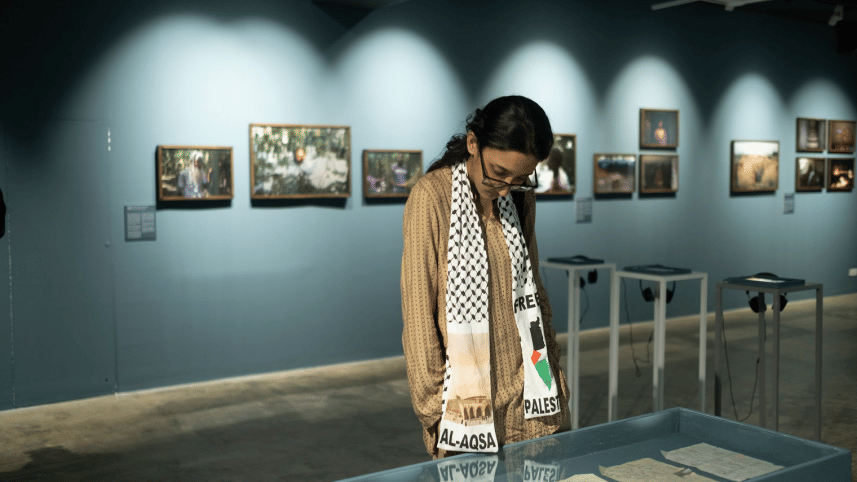

The moment visitors step into the gallery, they are greeted by a stark chart displaying death-penalty statistics from 2010 to June 2025 — a striking reminder of how many lives hang in uncertainty. The exhibition's title captures this paradox of existence — living while waiting to die.

The photographs depict ordinary moments: people sitting with family, resting in their bedrooms, or walking down a street. At first glance, they appear like any other citizens. But their stories reveal the haunting truth — each portrait belongs to someone who spent years on death row. These innocent people lived in fear every day, eating their meals thinking each might be their last. Their resilience, however, shines through. Despite losing youth, loved ones, and decades of life, they continue to persevere, refusing to surrender to despair.

One portrait shows Anwar Hossain, who spent 14 years in solitary confinement after being falsely accused of murder. His captions described the cruelty inside such cells. Another features Sheikh Zahid, who recalls, "Every time someone was taken for hanging, I thought this might be my last meal."

When asked about the entire process of the exhibition coming to life, Johan said, "I started actively working in 2022, but the idea had been with me for years and photography was the medium I chose."

Johan, who strongly opposes the death penalty, believes that no one has the moral right to decide who deserves to live or die. To bring this vision to life, he undertook extensive research — contacting lawyers, going through social media, and visiting all over the country to find the former inmates.

"I had to track down each of them through extensive research," he explained. "I spent 14 days with one of them but photographed for only three. The rest of the time was about building trust, making them feel safe."

Through "Living on Death Row", Johan hopes to ignite a conversation about the justice system and its consequences. He said, "There is little accountability for those who wrongfully imprison innocent people. My goal is to raise awareness and push for judicial reform." He also intends to advocate for compensation for those unjustly sentenced, seeing it as the first step toward restorative justice.

The exhibition stands as both art and activism — a reminder that behind every statistic lies a story, a family, and a life interrupted. "Living on Death Row" is not merely a showcase of photos; it is a call to see, to remember, and to seek change.

"Living on Death Row" is currently on display at Drik Gallery, DrikPath Bhobon, in Panthapath, Dhaka. Supported by the European Union, the Embassy of France in Bangladesh, Drik Picture Library, and The Death Penalty Project, the show opened on October 10, 2025, and will run until October 19, 2025, from 3:00pm to 8:00pm every day.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments