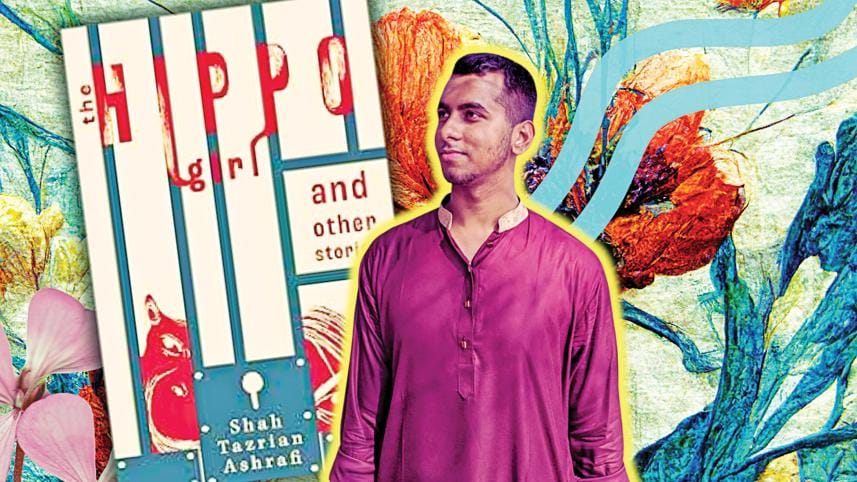

Outliers take centre-stage in Shah Tazrian Ashrafi’s debut collection

It's hard not to recall our many conversations about literature as I try to summarise Shah Tazrian Ashrafi's debut collection of short stories. They were always short discussions, opening and closing off in spurts, as happens over text. Exclamations over a new essay collection by Zadie Smith, or a new novel by Isabel Allende. During the Covid-lockdown, the gorgeous, gorgeous books I borrowed greedily from his shelf while book imports were halted—Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor's The Dragonfly Sea, Samanta Schweblin's A Mouthful of Birds. As a reader-friend and a writer whom I loved to edit, Tazrian always brought in books that wring history's strands to make space for the disadvantaged, books that take pleasure in challenging privilege and are interested in freedom and courage of character. This has always been his taste in literature and culture, from his earliest feature articles on SHOUT magazine to the critical, thought-provoking reviews he wrote for Daily Star Books. As an undergraduate student he majored in International Relations at BUP, but it's his growth as an artist that's been so fulfilling to witness. In 2021 he received mentorship from the Write Beyond Borders mentorship programme and in 2023, he was mentored by Karan Mahajan in the South Asia Speaks fellowship programme, an initiative founded by Sonia Faleiro—neither of these mentorship programmes was, however, for his debut collection. Between working on his debut book and publishing fiction and nonfiction in Himal South Asian, The Diplomat, Caravan, TRT World, The Aleph Review, Six Seasons Review, Dhaka Tribune, and The Daily Star, Tazrian also got accepted into the MFA in Creative Writing Program at UW Madison, due to start in Fall 2024.

The Hippo Girl and Other Stories (Hachette, 2024) plays with all those themes that have percolated in his essays and reviews over the years. The book stays often in the shadows of war, but illustrates moments of humour, friendship, and bravery between characters who are seldom on the upper end of a hierarchy. We hear from a dog who watches his human suffer through the Liberation War, a housemaid who must abandon her mentally disturbed sister in the calm streets of a fictionalised Baridhara. The textures of life in Bangladesh appear as they are in this collection, sans nostalgia or elitist gloss. It's a rare joy to recognize our familiar streets, customs, histories, and relationships depicted with such loving attention to detail in a book that will reach readers across South Asia. I first met Tazrian many years ago, when he reviewed the first short story I ever published in a book. My own writing went on to swerve far from fiction, while his relationship with it grew powerful and inventive through persistent hard work. This is the best kind of coming full circle to write about his first book-length work of fiction.

What inspired these stories? Were you drawing ideas or information from any particular sources?

There was no particular inspiration, but before writing these stories, I was fascinated by Petina Gappah and Jamil Jan Kochai's short stories. Their short fiction was etched in my mind because of how they managed to write about hopeless scenarios (often involving wars) in a palatable and light-hearted manner. As such, I actively looked back on their work to learn how they did and did not do certain things, especially in terms of subverting readers' expectations and upending assumptions. This is why I mention them in my synopsis. Besides, I was also inspired by Samanta Schweblin, Mariana Enriquez, and multiple stories from Commonwealth Short Story Prize and Caine Prize shortlists. The one thing they all share in common is their penchant for narrating stories of violence that leave the reader pondering about the characters for a long time. For instance, I got the idea for "Lucky" after reading this brilliant Caine Prize-shortlisted story called "Memories We Lost", which, like "Lucky", is about a pair of siblings in dire straits, ostracised by the society due to the stigma around mental health. Similarly, I was inspired to write "Indira Road" after reading a Commonwealth Short Story Prize-shortlisted story called "Something Happened Here"; in both the stories, the narrators return to their previous homes and revisit the unwanted forces that pushed them away in the first place.

We move through different classes in your book, from slums and working class families to diplomatic residential areas. But in all cases we're focusing on the outliers in each of these spaces—the bullied, the marginalised. What are your stories trying to accomplish through these gazes?

By giving the outliers the centre stage, I wanted to establish that some people are outliers in a society because of their helpless circumstances. My intention was to explore how certain factors intimidate and ridicule them and further consolidate their marginalised positions, as if to say they (the outliers) do not deserve a shot at life and redemption.

One way in which you do this—and this was my favourite thing about the book—is your choice of narrators. Nearly every narrator in the book comes with a distinct personality, they have their biases, their joys and resentments, even when you're writing a third person omniscient narrator. Some of the more fascinating narrators appear when you write in the first person collective. Tell me about your choice of narrators (the adults, the children, the animals). How did you want them to shape the stories you were telling? And how did you develop their voices?

I had a lot of fun writing in the first-person collective voice. I have always wanted to do that ever since I read NoViolet Bulawayo's story, "Hitting Budapest". I enjoy the limitless fluidity that this mode of narration gives me.

Writing in this as well as other modes of narration, one thing I hoped to accomplish was to give my narration a blend of humor, cynicism, and unreliability with generous doses of unforgiving observations. For example, my narrator in "Brother" was not only someone who constantly groaned about the Pakistani military's occupation, but he was also someone who derived small joys from playing hide and seek with his friends and seeing the physical altercation between two women. I wanted him to be a character who, despite living in gloom conditions, is in touch with his typical teenage characteristics from before the war. Like him, I wanted my other characters throughout the book to be defined by a myriad of other things besides their cruel fates. Some of them love reading, some love writing, some are academic high achievers, some refuse to let go of their intrinsic generosity even in the face of harshest conditions, and so on.

I recently had a conversation with another writer about how much or otherwise authors "care" about their characters, which can mean different things for different people. As writers, do we care for our characters by protecting them from conflict and suffering (which might not make them all that interesting to read about), or do we care for them through our attention to and perception of their pain? How much invented suffering is too much, and how much does justice to their realities? I feel like this book is very much a part of that conversation. What are your thoughts about this with regards to your characters' experiences in this book? How would you define your relationship with your characters?

I genuinely think it's the latter—we care for our characters through attention to their pain. I remember getting extremely sad after I finished writing "Brother", "Indira Road", and "Lucky". I had an epiphany to tone down their suffering a bit (as well as other characters' suffering in the rest of the book), but I stopped myself from doing that because in real life people suffer in much worse ways than these characters. I did not wish to shy away from highlighting this aspect of our existence. I am aware that many times my characters' circumstances can become a bit heavy for some readers, but as someone whose literary diet consists of mostly Dickensian tales, I could not bring myself to make any of the stories lighter.

My relationship with my characters has grown a little hazy considering it has been a long time since I submitted the manuscript. One thing I think about is their afterlives. They were some really unfortunate people living through some of the darkest human experiences, so I wonder if they're still chained to their suffering or if they have entered some kind of utopia where they can enjoy playing video games for limitless hours without their abusive parents sneaking up on them.

These are also the kinds of stories where the ending largely shapes the tone or the overall message. I'm thinking of "A Blazing History of Rage" —whatever disaster might await the two young boys who've run away from their abusive father, we end the story with the taste of freedom. "The Hippo Girl" climaxes on a similar note. But other stories like "My Human" and "Brother" take us all the way to the end of tragedies caused by war. How did you arrive at some of these endings and what meaning do they hold for you?

For stories like "My Human" and "Brother" I wanted to fully show the changes my characters went through as results of their tragic fates. I wanted to show how war can radically transform people. As for the other stories that do not have conclusive endings, I was interested in how certain moments of the characters' lives revealed some daring aspects of their souls that wouldn't get revealed otherwise. For instance, in the ending of "Crescent Boat", I was looking at how Sarfaraz displays an undisclosed side of himself (like showing affection for his estranged daughter) when he meets her after a long time. A side he is ashamed to publicise on account of his reputation as a stern man.

Luckily, I did not have to labour over finding the perfect end to my stories. The ending scenes automatically presented themselves to me. However, I was careful that, whatever the ending is, it should be shocking and unexpected while hinting at the protagonists' transformations. To keep a clear track of this, I relied heavily on the Five-Act Structure from Into The Woods: A Five-Act Journey into Story by John Yorke.

Religion and the Liberation War appear recurrently throughout the book. Can you talk about your approach to weaving them into these stories?

In my earliest days as a writer I used to fidget a lot to write stories surrounding the Liberation War. Reading A Golden Age, The Good Muslim, and Half Of A Yellow Sun fuelled the interest. I think the Liberation War weighed so heavy on my conscience that it automatically slipped into my stories. It was one of the major frameworks through which I often (unintentionally) imagined the stories for this particular book. Moreover, as a reader, I like reading stories that deal with war and its shadows. In a way, I suppose I was writing for myself. War stories allow for a lot of movement in terms of exploring a wide range of human experiences.

As for religion, I have noticed that many mainstream fictional works tend to depict it as a kind of authoritarian entity one must get rid of to embrace enlightenment. Once I came across Leila Aboulela's novels, I became fascinated by how she writes about piety and spirituality without coming off as preachy. That's what I wanted to do with my stories. I wanted some of my characters to find solace in something bigger than themselves. I wanted religion to act as a beacon of hope to guide them through the troubling times.

What I know of your journey as a writer from our editorial relationship is that you read and wrote relentlessly, participated in fellowships, you were constantly looking up opportunities and looking for feedback from authors and editors. What would you like to share with readers about these experiences? How did you develop your craft, how did you begin to work with your agent Kanishka Gupta and find a publisher for these stories?

It's a done-to-death kind of saying, but I truly think one needs to stick long enough to their passion if they want to elevate their art beyond the borders of a "hobby". I know many people who have been blessed with talent but the fear and exhaustion rising from rejections and self-doubt have completely worn them out.

I don't remember how exactly my journey as a writer began. But I remember, as an outlier in high school, I wanted to build an identity for myself besides that of an outlier. I was reading Anne Frank's The Diary Of A Young Girl at that time. Eventually, I began submitting my written works to The Daily Star's SHOUT. I got my breakthrough at SHOUT after a year full of rejections. Then I slowly moved on to undertaking more ambitious adventures like submitting to foreign magazines. That experience has also been marred by rejections but it has led me to quite a few bylines I am extremely proud of. I also made sure I was reading enough to develop my own literary voice and to be inspired by other trailblazers. It became a ferocious habit once I started my undergraduate studies because being away from mathematics and the STEM-related subjects gave me a breather I was in urgent need of. The act of writing was as important as reading, so I also kept myself occupied with writing stories, many of which, I am glad to say, will never see the light of day.

I found Kanishka towards the end of 2022. I have been a longtime admirer since 2018, and never in my wildest imagination did I think one day I could end up being represented by him for my debut collection. Finding a publisher is the literary agent's forte, so I did not have to worry much in that regard. He has a magician's hands. Once he accepted my manuscript, I was fairly certain my collection would be picked by any of the following: Hachette India, Penguin India, Harper Collins India, or Bloomsbury India.

What are you working on next?

I am working on my debut novel, which I am strongly hoping will become my MFA thesis. It's a mishmash of Midnight's Children, White Teeth, and One Hundred Years Of Solitude. I really hope the end-result will be as much fun as it sounds in the previous sentence. I am also working on another novel simultaneously, which will include another book within the book because the narrator is a writer. I am excited to see where this project leads me.

Sarah Anjum Bari is a writer and editor, pursuing an MFA in the Nonfiction Writing Program at the University of Iowa where she also teaches rhetoric and literary publishing.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments