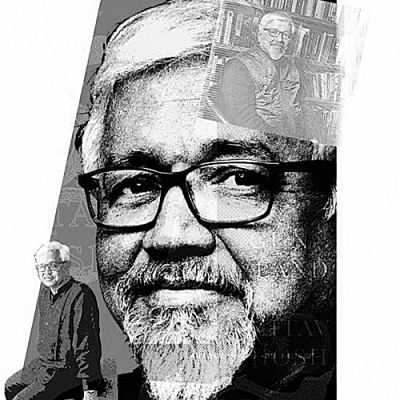

Climate and Fiction: Amitav Ghosh against Climate Change

There exists a deeply fascinating relationship between crisis and literature – either crisis gives birth to great literature or great literature offers an astute and substantial representation of crisis. Say, the decadence beneath the prudish Victorian morality or the existential crisis of bourgeois modernity or the effect of racism, sexism and colonialism on humanity, it is in literature where those crises were addressed with nuanced attention. However, a great crisis of contemporary era whose poisonous tentacles are pointed not only to humanity but also to the planetary existence of all life forms remains surprisingly understated in 'serious' modern fiction – the crisis of climate change.

Climate has a contradictory existence in literary imagination. Climate, as a subset of what we call nature, has always found in the pages of poetry and fiction in the form of meteorological phenomena like rain and storms. And speaking of nature, it has always served as a storehouse of images, similes, and metaphors for all genres of literature. There are great literary works which are imbued with a kind of ecological sensitivity that makes us reflect on the beauty and magnificence of nature and how nature and life are attached together by a symbiotic connection. In the poems of the age of Romanticism, in Rabindranath Tagore's Chinnapatra and the lyrics categorized as 'Prokriti Porbo', Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay's Aranyak and Amitav Ghosh's The Hungry Tide such deep sensitivity is found among many other works. Whereas literature cannot do without nature and climate, the crisis of climate change which threatens both nature and human, has hardly been addressed in modern fiction – an observation made by none other than Amitav Ghosh.

In his 2016 non-fiction, The Great Derangement, Amitav Ghosh asks why 'serious' modern fictions are finding it difficult to accommodate the question of climate change. Although a good number of writers are found to raise their anxiety over carbon economy and its repercussions on nature and climate, that anxiety is not expressed in their fictional works. Ghosh names Arundhati Roy, Paul Kingsworth and himself who are informed and conscious about climate change but their concerns are expressed in the medium of non-fictions. Even when the question appeared in their fictions that too very obliquely and sporadically. In the academic circle, works on literary ecology is increasing significantly under the umbrella of ecocriticism but that too are wanting in primary texts of fiction which address the crisis of ecological catastrophe. Ghosh's concern over contemporary fiction's failure in portraying the climate crisis leads to a more fundamental question, which touches on the very logic behind the functioning of modern fiction. He thinks that the problem lies in the conventional mode of fiction writing which hardly allows anything that does not comply with the bourgeois rationality. Whatever this rationality fails to capture in its radar, simply eliminates them from its landscapes. Ghosh uses the word 'improbable' to denote these outcasts. In modern novels, the narrative follows a continuum of probability where improbable events appears as a gradient that must be left out in order to look 'normal'. In Derangement, evoking Franco Moretti's works, Ghosh discusses at length on how modern fiction has maintained narrative compatibility with the regularity of bourgeois life that has rendered the mention of the 'improbable' as obsolete, unmodern and unscientifically illogical. Whenever improbable episodes appear in literature, they do so under the umbrella of special nomenclature, segregated as sub-categories like surreal or magic-real. In public imagination, climate change and global meteorology evoke the images of the calamities which happen on the other side of the world and very irregular and improbable in their everyday life. On top of that, everyday life in capitalism has been normalized to a zone where people's vision has been confined within their immediate interests. So, climate change has hardly become a relevant concern in the lives of urban civilization. This tendency of evading the apparent improbable determines the narrative imagination which makes the fictional representation of contemporary climatic reality exiguous. So here, the crisis of climate becomes a crisis of culture and thus of imagination too, as Ghosh claims. It should be noted that literary productions of an era are ideologically conditioned by the dominant mode of production. And it's no secret that capitalism and its exploitation of nature is responsible for the climatic disaster. On the same note, it is capitalism by the maneuver of its ideological apparatuses resist the climate crisis being addressed in the literary productions. Held in this trap, modern fictions are failing to portray the contemporary climatic reality.

After the Derangement, it was kind of expected that the writer of Ibis Trilogy would try to address these questions himself in the medium of fiction and in his new novel Gun Island, he exactly does so. The novel begins with a reminiscence to The Hungry Tide, Ghosh's 2004 novel set in the Sundarbans as some of the familiar characters from that novel reappear. The story is told in a first-person narrative, by Deenanath 'Deen' Datta. The story begins with Deen's encounter with the legend of the Gun Merchant (BondukiSadagar). The legend follows a similar narrative like that of Chand Merchant (Chand Sadagar) and Manasa Devi, the goddess of serpents. As Deen has a Ph.D. on Bengali folklore, he is requested to visit the dhaam, the shrine of the merchant located in an island deep inside Sundarbans. Though reluctant at first, Deen complies and sets his journey towards that shrine which turns his regular, uneventful life into one full of inexplicable and perplexing happenings. It is in this journey, he meets Tipu and Rafi, two teenagers from the mangroves and their connection continues until the final pages of the book. In the shrine, Deen confronts a snake which ends up biting Tipu and then an array of coincidences and improbable events slant the continuum of Deen's normal life. Deen regrets this visit and tries to forget it when he gets back to New York, where he lives, but the chain of events pushes him to confront more implausible episodes which finally make him board in a ship that goes to rescue a boat of immigration seeking refugees in the Italian coastline.

In the unfolding of the narrative, two issues become conspicuous – the question of climate change and the immigrant problem and in many cases, their entwined connection. The way climate change is affecting the Sundarbans and the people symbiotically connected to the ecosystem of that forest is broached here. Rafi and Tipu represent the people who are losing their traditional livelihood and turning into climate refugees as the sea-level is rising and salinity is invading the freshwater. The journey of Rafi and Tipu from the muddy swamp of mangroves to the glamour of European life exposes the perils the immigration seekers have to go through. By the same token, the novel sketches the thriving of extreme rightwing politics that sustains on the anti-immigrant sentiments. The link-up between the climate crisis and anti-immigrant politics in this novel exposes the challenge to what Dipesh Chakrabarty calls the idea of a 'global, collective life' necessary to battle the threats of climate change in his seminal essay "The Climate of History". However, the most remarkable aspect of Gun Island is that here Ghosh attempts to break free from the logic of narrative imagination he critiques in the Derangement. Improbability is the leitmotif of this novel. The narrative progression is overdetermined by an array of improbable coincidences and unlikely occurrences. Here, the influence of nonhuman agents on human behavior is given significant attention too. The characteristically anthropocentric attitude of the era called 'Anthropocene' has negated the effect of the nonhuman interlocutors like the flora and the fauna, objects and nature in shaping the course of human thought and history. In this novel, human thoughts and actions are influenced by erratic meteorological phenomena, snakes and spiders, birds and cetaceans. In Gun Island, the 'irrational' creates its own space of rationality where the 'improbable' and the nonhuman are active agents.

Gun Island is no doubt an ambitious project by this celebrated South Asian novelist. Since the release of The Great Derangement, it was anticipated that Amitav Ghosh would make such an attempt and Gun Island perhaps marks the beginning of a series of novels where the writer will deal with the question of climate change and its locus in contemporary novels. This novel is also a wakeup call to his fellow fiction writers. It is to remind them that the climate crisis is real and they must play their part to fight it. This is an obligation the tradition of literature has conferred on writers.

Raihan Rahman is an electrical engineer by profession. After completing his graduation from BUET, he did an MA in English Literature from ULAB.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments