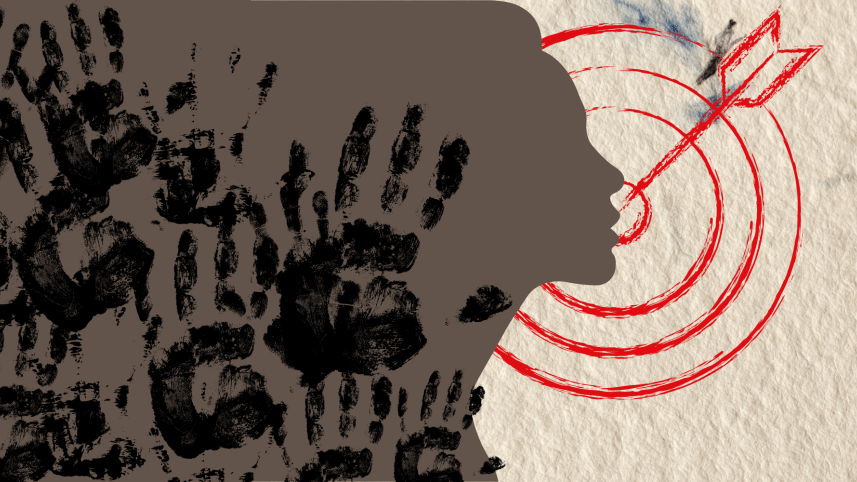

Sexual harassment in universities and the struggle for justice

In a conversation with my mother about recent events, the topic of sexual harassment in universities came up. With a heavy heart, she spoke candidly about how none of it was new and that no one used to speak up during her days as a student. Her words struck a chord, reflecting a painful truth. Despite progress, silence has long shrouded this issue. As I glance at my surroundings, her sentiment resonates deeply. The echoes of unspoken stories serve as a stark reminder of the enduring struggle against injustice.

According to data provided by the University Grants Commission (UGC), just 97 and 45 of the country's 114 private and 55 public universities have established sexual harassment prevention committees. Despite a High Court directive issued 15 years ago, approximately 16 percent of the nation's universities have not established sexual harassment prevention committees. The UGC has regularly failed to receive information regarding the operation of university complaints committees. Only a few universities provide information.

Because many students are unaware that these committees exist, many cases of sexual harassment go unreported, making it impossible for victims to seek justice. But when students step up only to be met with indifference, what can they do?

The recent case of Fairuz Abontika, a student of Jagannath University's (JnU) Law Department, is a painful reminder of how incompetent universities are in dealing with sexual harassment complaints. In her suicide note, she stated that she complained to the proctor's office that her harasser was threatening her offline and also online, but to no avail, as the designated proctor himself started threatening her. In an interview with Desh Television, another student from the same university, Kazi Farjana Mim, discussed the hardships she endured at the time simply for complaining to the Vice Chancellor. Unsurprisingly, no action was taken.

These past few years have seen a significant surge in reports of sexual harassment coming to the forefront. This included complaints against students as well as teachers. Alongside these revelations, a lesson has been learned: many students opt to remain silent about their experiences, primarily due to universities' perceived inaction. Students frequently worry about the consequences of sharing their experiences. Occasionally, universities are compelled to respond when confronted with student-led protests, as evidenced by recent events at Dhaka University (DU) and Chittagong University (CU).

The institutional reaction to sexual harassment in universities often treats it as an isolated experience, which is problematic. In the last two years, 27 incidences of sexual harassment have been reported at the country's five reputable universities. The real number is much higher because most victims do not complain in fear of academic difficulties, unfair reverse allegations, distrust of legal processes, and, most importantly, fear of social stigmatisation.

Sexual harassment encounters are framed as individual incidents using a legalistic approach for both the definition and complaint procedures. A legalistic approach to sexual harassment on campuses is ineffective and insufficient, but it could be a decent starting point for addressing institutional accountability. However, in Bangladesh, legalistic approaches are often ineffective because most students do not report their experiences. In a 2023 study by Dr Abdul Alim, a law professor at Rajshahi University (RU), interviews with 200 students revealed that 90 percent of harassed female students chose not to report their experiences while attending the institution.

Unfortunately, the focus of the institutions is always to employ "damage control." For instance, on March 14, a teacher at Jatiya Kabi Kazi Nazrul Islam University in Mymensingh was permanently suspended after sexually harassing a female student in the face of protests. Universities fail to punish harassers, especially tenured professors, in a fair, prompt, and consistent manner. Tenured professors often receive temporary suspensions, as we've seen in the case of Dr Wasel Bin Shadat. Students who sexually harass other students face suspension, dismissal, or expulsion if found guilty. Sexual harassment is a criminal offense. Therefore, this crime should be punished as other criminals are prosecuted.

A legalistic approach to university terminology and complaint procedures may have consequences for sexual harassment, but it ignores the broader context of discrimination, power relations, and equal opportunities. Punitive actions alone do not address the root cause of the problem. Increasing female faculty and leadership representation in universities is vital. Structural reforms, led by women in positions of power, are necessary to combat institutionalised sexism. Although a complete transformation is ideal, practical adjustments made at the hierarchical level are essential to ending discriminatory practices like sexual harassment.

Universities should go beyond legal compliance to address harassment issues while enforcing transparency and accountability. Additionally, adhering to designated positions without looming power imbalances between faculty members and students should be encouraged. This can extend to dominance practised within the student body itself, where power imbalances emerge between seniors and juniors. It is also necessary to increase the number of committee members to conduct timely investigations as well. To broadly address sexual harassment as a systemic issue, cultures that promote it, such as male dominance, lack of diversity, and lack of accountability, must also be addressed in order to begin tackling the complexity at hand.

Educational institutions, including universities, should serve as safe spaces for students. Governing bodies must ensure that any student encountering similar challenges can confidently lodge a complaint without fear of blame, shame, or neglect. Individuals have the right to determine when they are ready to report. Students deserve effective reporting mechanisms that promote accountability and systemic change. One's voice should not only resonate amidst protests; a singular presence should suffice for one to be acknowledged.

Azra Humayra is majoring in Mass Communication and Journalism at the University of Dhaka. Find her at: azrahumayra123@gmail.com

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments