Soaring Prices Of Commodities: Lower-income people hung out to dry

For the last two months, 35-year old security guard Saiful Islam could not send any money to his parents living in a village in Rangpur, one of the poverty-stricken divisions in Bangladesh.

Rickshaw-puller Miraj Shaikh is failing to put aside money for the treatment of his three-year-old baby.

Day labourer Anisur Rahman Mondol could not provide any meat to his family.

And van-puller Shahin Hawlader is considering returning to his village from Dhaka if the ongoing cost of living crisis persists.

These are the stories of distress of the low-income people and similar stories of struggle, anguish and helplessness could be found if you ask the low-income people in your neighbourhood about how they are coping with the high prices of essential foods.

The spike in the prices of key food items and other costs has eaten up much of their purchasing capacity, made their struggle harder and shattered their hopes to live a better life.

And it came at a time when many of them had hoped to make a turnaround as economic activities picked up from the coronavirus pandemic-induced economic slowdown and on and off lockdowns, which destroyed much of their income opportunities.

Officially, one-fifth of the nearly 17 crore population are poor but private research organisations say the number of poor people has increased after the pandemic hit Bangladesh. Now, the rise in the cost of living, fueled by higher commodity prices amid the Russia-Ukraine war, has dashed their recovery hope.

"It has become difficult for me to bear the family expenses amid the surging prices of essentials," said Abdur Rahman, a street vendor, who sells fruits in Mirpur in the capital.

"So, I have cut back on the costs on daily groceries to strike a balance between the expenses and my income," said Rahman, who has become the sole breadwinner of the six-member family after his father became sick in 2016.

Before the latest price shock, the 25-year-old used to spend around Tk 5,000 per month to buy rice, fish, eggs, vegetables, meat and other basic items. Now, he has to make do with Tk 3,500.

"It hurts. But what else can I do?" asked Rahman.

Saiful Islam works as a security guard at a house in Mugda for a monthly salary of Tk 10,000. He has to spend Tk 4,000 as house rent for his three-member family.

Even two months ago, he had to send Tk 1,500 to his parents living in the village and set aside Tk 1,200-1,300 for his two-year-old son.

The rising cost of living has forced him to cut down on the budget for his son by a quarter. He also has not been able to send any money to his parents in the last two months. "My parents are relying on personal loans to survive," Islam said.

"Life has become miserable for us. How long will we have to survive eating rice, pulses and potatoes?"

Prices of rice, flour, pulses, oil, fish, meat, vegetables, soap and milk rose by 12 per cent in February, according to a report of the Consumers Association of Bangladesh.

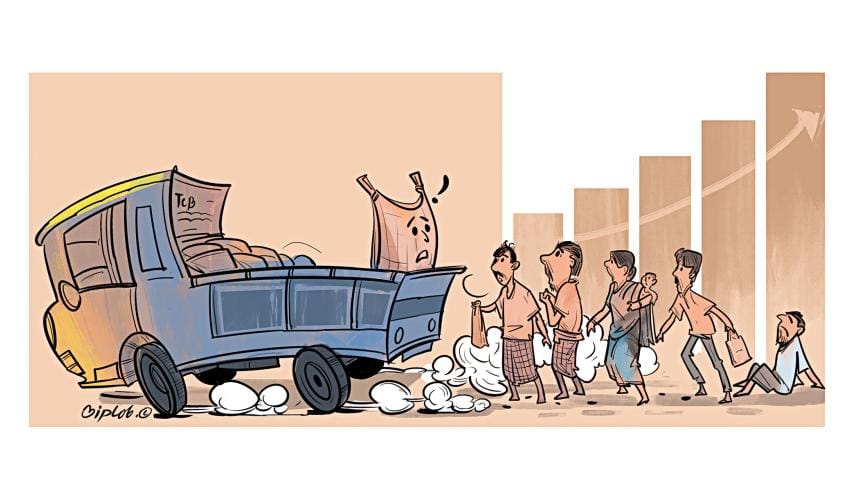

The prices of essentials, including flour, edible oil, sugar, red lentil, eggs and onions, have gone up by 10 to 40 per cent in the past one year, data from state-run Trading Corporation of Bangladesh (TCB) showed.

In Bangladesh, inflation has been at a higher level for the elevated commodity prices globally, fueled by supply constraints, pent-up demand and unprecedented shipping costs.

Inflation rose 6.17 per cent in February, according to the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics.

Miraj Shaikh lives in the capital's Agargaon area with his four-member family. He rides a rickshaw and can save Tk 300-350 every day after meeting all expenses.

His three-year-old son's heart has a hole and for this, he has to take him to the hospital every three months for a regular checkup.

"Doctors have told us an operation will be possible when he turns five. So, we have been depositing some money regularly for him. But we have not been able to save any money for him in the last three months," he said.

Shaikh's monthly budget for rice was Tk 1,100 before the price hike. But because of the rising expenditures, he can't afford the same quality rice as in the past.

His family used to eat eggs four days a week and fish once a week. "Now, we eat eggs twice a week. We eat rice with vegetables and lentils during the rest of the week," said the 27-year-old.

Anisur Rahman Mondol, a daily-wage labourer in the capital's Gabtoli area, earns Tk 300-350 a day and lives in a rented room with wife and four children.

"None of my family members have eaten fish or meat for nearly a month. When my children ask me why there has been no fish or meat, I have no answer."

The average prices of pumpkin, cauliflower, cabbage, papaya, green bean, gourd, cucumber, brinjal, radish, carrot, tomato, and pea have risen by about 60 per cent. Ayesha Begum works as a domestic help in Kachukhet and earns Tk 9,000. She became the breadwinner of the four-member family after losing her husband a few years ago.

"What I earn today is not enough to run the family. So, I have borrowed some money," said the 33-year-old.

The family's house rent is Tk 3,500 and it has been unpaid for the last two months.

"The homeowner has already told me to clear the dues or leave. I am at a loss," she said.

Afsar Ali, a construction worker, came to Dhaka from Barishal 20 years ago. He lives in Merul Badda with his parents, wife and a daughter, who has been divorced recently.

"My family can afford only rice and smashed potatoes twice a day instead of three meals a day," said the 50-year-old, as tears welled up in his eyes.

Joy Charan Das works as a cobbler in the East Tejturi Bazar area. He says six months ago, he could afford rice, eggs and fish two to three days a week.

"Now someday I eat rice, someday I eat ruti."

The sexagenarian has heard that the government is giving cards to the poor people to help them buy food items at subsidised rates.

"I don't know where to go," he said.

As the prices of daily essentials have soared, the government has distributed cards among 87.10 lakh households in Chattogram, Sylhet, Rangpur, Rajshahi, Khulna and Mymensingh divisions since March 20. The card-holders will get edible oil, sugar, lentils and chickpea at subsidised prices under the open market sale operation of the TCB.

Shahin Hawlader, a 50-year-old van-puller in the capital's Vasantek area, says the monthly expenses of the family have increased by Tk 1,500-2,000 but the income has not.

Already he has reduced the expenses on essentials and medicines.

"I will observe the situation two more months. If the scenario does not improve, I will go to the village with my family."

Nazma Shaheen, a professor at the Institute of Nutrition and Food Science at the University of Dhaka, says whenever a person's economic condition worsens, he or she cuts down on food consumption first.

But if they don't take the minimum required calories and ensure a balanced diet, they would ultimately suffer from malnutrition, she said.

"Support is being given through the TCB, but not everyone is getting it," said Binayak Sen, director-general of the Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies.

He called for policy intervention to supply essential items to the poor at a lower price when they become dearer.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments