A wounded economy, another perilous year

It's not the best of times. It's not the season of light. The future will tell whether it's the period of Dickensian despair on the economic front. But this is not the moment for business as usual, for sure.

The cycle of economic exhilaration that portrayed Bangladesh as a stellar performer in Asia for a decade is no more on the steady ground that it once was. A triad of crises is now seeping into every corner of the economy. Inflation is an index of chronic consumer pain. The exchange rate shock is hurting almost everyone. Foreign exchange reserves are still haemorrhaging -- half a billion dollars per month.

A sea of red ink appears on the horizon as almost all indicators depict a gloomy picture. GDP growth has come down from its exuberant peak. Stock prices continue to drift downward. Most banks, save for a dozen, are lurching in and out of fund shortages. The zombie banks kept alive for too long are dragging the sector down.

Is the economy becoming a chronic patient? Perhaps not. But it's grievously bruised and needs to be healed and fast.

Years of stability lulled us into believing everything was perfect. People in almost every sphere became habituated to an equilibrium of low inflation, low interest rates and low exchange rate volatility. Under this apparent calmness was a layer of stress.

Then the global crisis came more as a trigger than a cause, exposing Bangladesh's vulnerabilities. Now the tinted perception of the economy is wearing off, acceptance of which we are resisting.

The new fiscal year starting in July could be another perilous year amid a confluence of global economic headwinds and the lingering effects of the government's past misguided steps.

As Abul Hassan Mahmood Ali unveils fiscal goals in his maiden budget as the finance minister today, he will come under sharper scrutiny than his predecessors who managed the economy in the past 15 years.

Sadly, Ali has inherited a wounded economy, but he doesn't have to live with a controversial legacy left by AHM Mustafa Kamal, his immediate predecessor, whose 6/9 percent interest rate formula that afflicted the banking sector for three years will go down in history as the most perverse practice. Its toxic fallout, some say, still lingers as it created unnecessary aggregate demand for credit leading to inflationary pressure. Inflation, equivalent to a highly regressive tax on already stagnating wages and salaries, doesn't seem to be coming down to a tolerance level so soon. It will be a long slog for the government to tame consumer prices.

Ali, 81, was well known for foreign service, but not so much for economic management. Still, the heavy lifting of budget planning fell on his frail shoulders right after he took the helm of the country's finance ministry in January. And it's playing out at a time when Bangladesh faces one of the worst economic crises in history. Now, he is diving into a territory that requires a coordinated policy approach to bring the economy back on track.

That's an enormous task.

Two years in a row, fiscal policy failed to heal festering wounds. But the new budget presents an opportunity for the new minister to reveal a vision to turn things around. Ali faces a difficult trade-off between maintaining economic growth and strengthening public finances.

One of his fiscal goals is a narrower budgetary deficit equal to 4.6 percent of the gross domestic product, a clear departure from the golden rule of the 5 percent gap that Bangladesh has followed for ages with some exceptions. Some economists say the new deficit plan is still too high. The issue is not debt sustainability but macroeconomic stability because more than half of the deficit financing will come from domestic borrowing. That could either come in conflict with monetary policy targets to reduce domestic credit growth or severely crowd out private credit by driving interest rates too high. The economists suggest it should be contained to 3 percent of GDP at least for fiscal 2024-25, another uncertain year, to reduce the burden.

"The main elements of the budget strategy should be to reduce fiscal deficit significantly to lower aggregate demand. This demand reduction should be achieved in a way that it does not compromise the future growth prospects," said Sadiq Ahmed, vice-chairman of the Policy Research Institute.

For this to happen, the strategy involves raising tax revenues through effective reforms, increasing the profitability of state enterprises through corporate governance, reducing unnecessary subsidies, and increasing spending on education, health and social protection, according to Ahmed.

Bangladesh's tax-to-GDP ratio is a long-standing fiscal weakness. At 7.3 percent of GDP, this ratio is one of the lowest in the world. Revenues continue to be underwhelming due to tax exemptions, weak administration and challenges in implementing tax reforms.

The budget day is a cacophony of big numbers that drowns out the need to cushion the poor against price shocks. The finance minister is expected to do more than just keep the poor in his thoughts. Urban poverty is deepening. In Bangladesh, more than 18 percent of the population lives under the poverty line and another 20 percent, as research organisation SANEM suggests, are very vulnerable and run the risk of falling into poverty due to any shock.

"The budget should look at the pressure heaped upon the marginalised groups, the fixed-income groups, and the low-income people, and how they can be helped through budgetary allocations, fiscal policies, and fiscal incentives," said Mustafizur Rahman, a distinguished fellow at the Centre for Policy Dialogue, a think-tank.

One easy way to free up funds for social protection is by cutting subsidies as the International Monetary Fund suggests. By loosening the exchange rate further, Bangladesh, for example, can eliminate subsidies on exports and inward remittances. However, some agriculture input subsidies on fertiliser, seeds and irrigation are necessary. Overall, it is possible to reduce subsidy spending from a high of 1.9 percent of GDP in FY2023 to 0.8 percent of GDP in FY2025, according to an estimate by Sadiq Ahmed of PRI. These savings can be redeployed to healthcare, education and social protection.

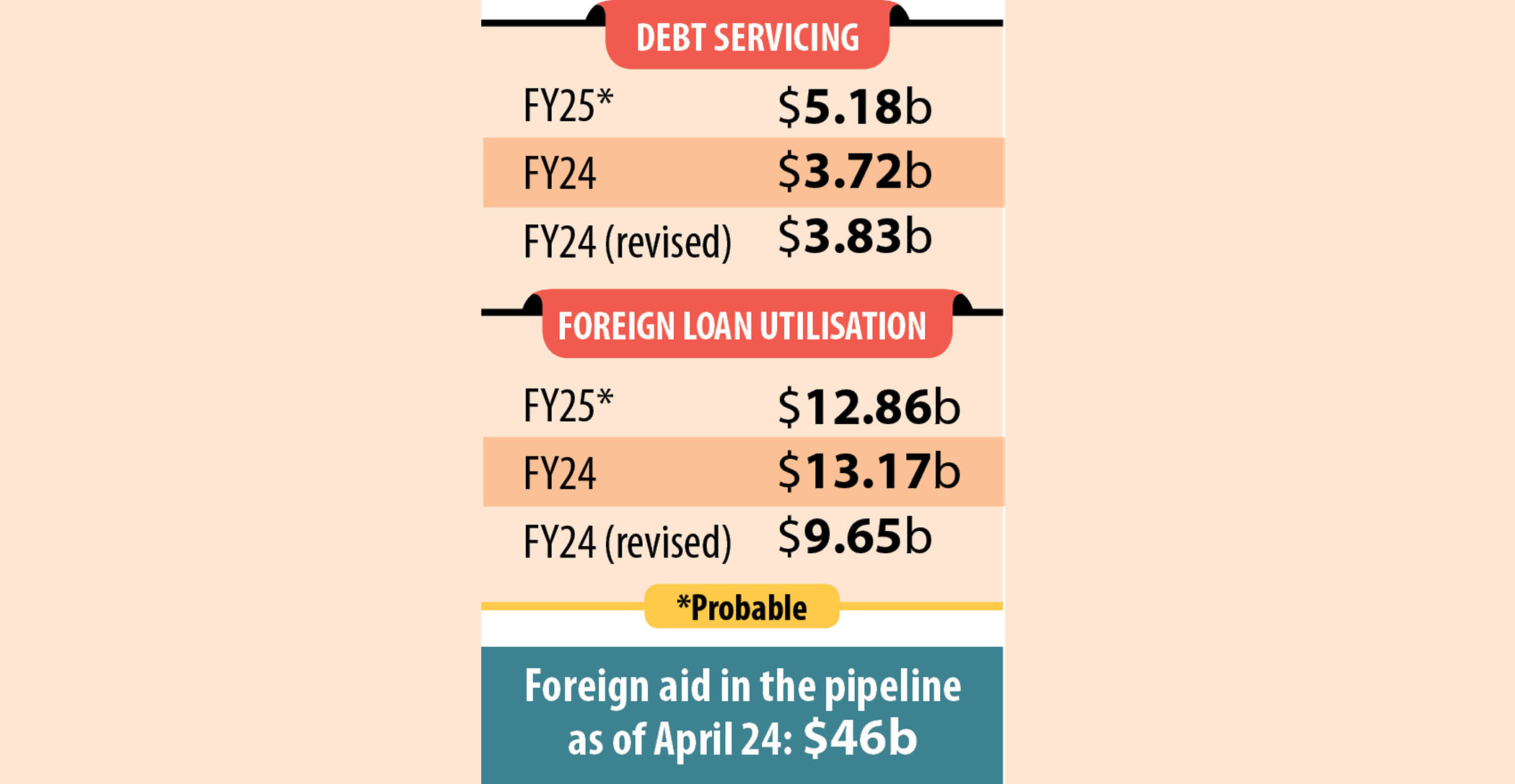

In the new fiscal year, the government will bear a heavier burden of interest payments. So, the allocation for interest payments of domestic and foreign loans will likely jump more than 20 percent to an all-time high. The government has already intensified local borrowing to plug the fiscal deficit, pushing the yield on treasury bonds and bills to a peak. While it opened an avenue for investors to park money in government securities, it has some consequences. Public debt accumulated through treasuries is largely a way to transfer funds from taxpayers to wealthy bondholders, as famed French economist Thomas Piketty argues.

In the run-up to the budget, there were some refreshing changes, albeit pushed by the IMF. In early May, Bangladesh made three major decisions to cushion the economy against critical risks such as stubborn inflation and forex erosion. In a rare move, the central bank let the local currency slide by the most in a day against the mighty dollar. Bangladesh Bank also raised the key policy rate for the second time this year and made lending rates market-based, abandoning a treasury bill-linked formula for banks.

These steps testify to the authorities' belated realisation. Realisation, nonetheless.

This year's budget is coming at a very distinctive time in the history of Bangladesh's economic development. While the budget is simply an estimate of government revenues and expenditures for a fiscal year, it's also an occasion for soul-searching -- a day of reckoning.

It's time to gaze inward.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments