The risk of becoming: Notes on translation and transformation

Translation is risk, and poetry is the highest form of risk. To translate a poem is to follow it into the flame, risking that what survives the burning is no longer what first arrived. Accepting this, I have undertaken the translation of Late Prabuddha Sundar Kar's Bangla poem "Jhuki" into English. The poem, originally published as the first poem in the poet's Mayatānt (2001) collection, appears below.

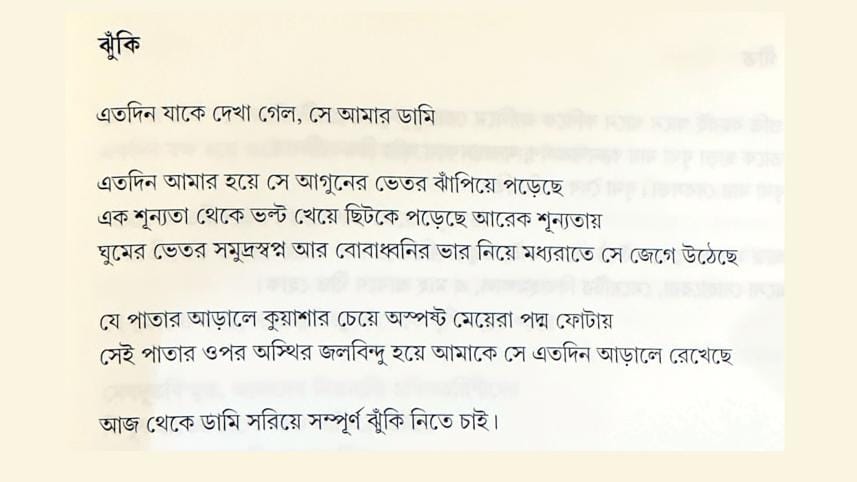

Jhuki

Etodin jāke dekhā gelo, se āmār ḍāmi

Etodin āmār hoye se āguner bhetor jhāpiye poṛechhe

Ek śūnyatā theke vōlṭ kheye chiṭke poṛechhe ārēk śūnyatāy

Ghumer bhetor samudra-swapna ār bobā-dhwanir bhār niye madhyarāte se jege uṭhechhe

Je pātār āṛāle kuyāśār cheye aspaṣṭa meyerā padma phoṭāy

Sei pātār opor assthira jalabindu hoye āmāke se etodin āṛāle rekhechhe

Āj theke ḍāmi shōriye sampūrṇa jhuki nite chāi

This poem resides in the threshold between two selves: the self that has lived as a protective shell and the self that emerges once that shell is rejected. Translation of such a poem is never a simple linguistic operation. It is a negotiation with identity, illusion, and silence. A poem like this does not ask to be carried across languages. It asks to be awakened through a second life. It requires listening not only to language but to the psychic architecture hidden beneath language. At its core, "Jhuki" is a poem about the perilous act of becoming. The speaker sheds a constructed self, the dummy, that has long absorbed pain and illusion on their behalf. This shedding is violent yet necessary, a psychic rebirth where the self risks exposure to authenticity. In this poem, identity is not a stable self. It is a layered shell. The dummy is a defensive persona that has stood in for the speaker. It has been seen instead of the true self.

What becomes clear in this work is that pronouns are not neutral. The Bangla phrase "jāke dekhā gelo" (The one who has been seen) keeps the speaker displaced from the one observed. A crucial psychological distance resides there. Not "I saw" but "The one who has been seen." Psychoanalytically, the self is viewed from outside, as if the narrator is encountering the ghost of an ego constructed for survival. This dummy is not a puppet. It is a provisional self that has substituted true experience. The translator needed to preserve this psychic distance. Keeping the English line impersonal protects the poem's dissociated gaze.

Walter Benjamin wrote that the translator must reveal the relationship between languages that is hidden inside the original text. According to him, translation is not a copy. It is a continuation of the poem's "afterlife." In "Jhuki", that afterlife is already embedded in the poem. The speaker stands on the edge of a transformation that has already begun. The poem itself is in a state of metamorphosis. So the translation must become part of that change rather than simply describing it. Its tense is not retrospective but continuously happening. So the translation remains in the present perfect–the tense of ongoing transformation rather than closure.

The imagery of leaping into fire provided another challenge. The instinct of an insect rushing to flame is not heroic. It is a compulsion of desire and destruction. Freud named this compulsion the death drive (Todestrieb). A desire for release through self-ruin. The dummy absorbs the death drive. The real self is preserved by letting the false self burn. Bangla diction evokes this helplessness. Therefore, English needed to resist the temptation of romanticising the leap. "It has rushed into fire" restores the instinctive self-harm that the original contains. The dummy is driven by its own self-annihilation, perhaps because that is the only way to keep the true self untouched.

The act of "vōlṭ kheye chiṭke poṛechhe ārēk śūnyatāy" (vaulting outward) suggested abrupt propulsion. The psyche does not glide from one emotional void to another. It is hurled. This creates a kinetic structure in the poem, a movement through emptiness that gave the translation its spine: vaulting outward from one emptiness and flung into another. A rhythmic echo of the poem's vertigo.

The lines "Ghumer bhetor samudra-swapna ār bobā-dhwanir bhār niye" (carrying ocean-dreams in sleep and the weight of voiceless sound) and "madhyarāte se jege uṭhechhe" (It has awakened in the middle of the night) form the poem's deepest point of psychic tension. Within "ghumer bhetor" (within sleep), the self is submerged in the interior landscape of the unconscious, drifting through "samudra-swapna" (ocean-dreams) that recall Freud's notion of the "oceanic feeling," that primordial sense of dissolution before the birth of selfhood. Yet those dreams are burdened with "bobā-dhwanir bhār" (the weight of voiceless sound), an image of language trapped inside emotion, where sound exists without articulation. This is the gravity of repression, a language that has not yet found its mouth. When the poem reaches "madhyarāte se jege uṭhechhe", that awakening is not gentle but seismic. The dummy rises involuntarily, compelled by the pressure of what it has carried through sleep. Psycholinguistically, this is the moment of passage from affect into speech, from latency into consciousness. The night becomes the porous threshold where silence begins to turn into utterance.

In translation, this demanded a rhythm that mirrors the slow breaking of a wave: Carrying ocean-dreams in sleep / and the weight of voiceless sound, / It has awakened / in the middle of the night. The cadence holds the pulse of emergence, as if consciousness itself is surfacing from darkness, trembling with the knowledge that every awakening carries the risk of unmaking what was safe.

Then comes the mist. And girls summoning lotuses into bloom. Here, the language enters a dream-topography. Psycholinguistically, the unconscious voice emerges in metaphors that bypass the rational. The dummy becomes a droplet of water, hiding the true self. The translator must learn to listen to the silence inside metaphors. Behind the leaf is not a place. It is a sanctuary of concealment. A secret interior scene. Translation has to protect that intimacy of concealment, because the poem's revelation emerges only from hiding.

Finally, the poem arrives at its violence. "ḍāmi shōriye" (sloughing the dummy) is not simply removing. It is shedding of skin. A snake does not discard its skin gently. Shedding is a rupture. The old surface of the self peels away and drops to the floor. Only through pain can the true surface breathe. Therefore, I chose "sloughing the dummy" because the word carries the biology of transformation. The phantasm-self is torn away in order for the authentic self to risk exposure.

The poem's tense demanded the present perfect because the injury and awakening have not been completed. According to Benjamin, translation is the echo of the original in a new constellation. In this constellation, the poem's afterlife becomes the moment of choosing danger over disguise. Translation, therefore, becomes a ritual of shedding. Each line is the slow removal of a false skin. The poem is not about the dummy–it is about what remains after the dummy falls.

The poem's imagery of leaping into fire, awakening from oceanic sleep, and tearing off an old skin all point to one truth: transformation demands danger. In that sense, the poem mirrors the act of translating poetry itself. Every translation must slough off the comfort of the original form and risk its own dissolution in another language. The translator, like the speaker, must enter the flame knowing that what survives will not be identical to what began. Translation becomes its own "Jhuki", a shedding of linguistic skin, an awakening through loss, and a conscious acceptance that the reborn poem will carry both the scars and the freedom of its metamorphosis.

Now, let us see what "Jhuki" has become through the quiet metamorphosis of my translation into English.

The Risk

The one seen so far has been my dummy.

It has rushed into the fire so far on my behalf.

Vaulting outward from one emptiness, it has been flung into another.

Carrying ocean-dreams in sleep and the weight of voiceless sound,

It has awakened in the middle of the night.

Behind the leaf where mist-blurred girls summon blooming lotuses,

It has kept me hidden so far as a restless waterdrop upon that leaf.

From today, sloughing the dummy, I want to take the full risk.

Naseef Faruque Amin is a writer, screenwriter, and creative professional.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments