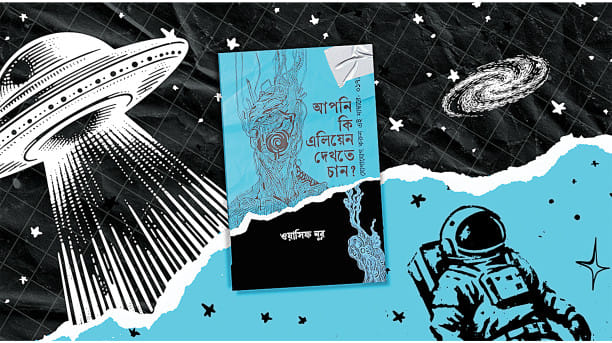

‘Apni Ki Alien Dekhte Chan?’: A debut with immense possibility

From the early 2010s, Bangladeshi genre literature has been going through a silent revolution. If you want to get technical about it, you could argue that such trends started much earlier, with Zafar Iqbal introducing elements of foreign literature and subsequent writers borrowing liberally from Western supernatural traditions through the inclusion of monsters such as vampires and mummies. But those books—more often than not—were cheap cash grabs, regurgitative copies of popular intellectual properties, or IPs, such as Goosebumps and Stephen King novels. This started changing during the early 2010s, and efforts such as Mashudul Haque's Ventriloquist (Baatighar, 2013) tried to incorporate foreign supernatural elements in a way that they seamlessly entwined with the setting of Bangladesh.

Now, what's the verdict on such attempts? While early titles like Ventriloquist succeeded to a certain extent, writers who later followed this path made the mistake of making their stories too fantastical or too outlandish. The sequel to Ventriloquist, Minimalist (Abhijan Publishers, 2020) certainly made an effort to stick to the naturality of the original book, but it quickly fell into the trap of devolving into a convoluted thriller, AKA Masud Rana, and the second half of the book suffers immensely as a result. I remember reading a book titled Gadfly (Adi Prokashoni) by Muradul Islam in early 2015 where it followed the outlandish plotting of a Masud Rana book to the T, so much so that even when I was done with the book, I still couldn't recognise the Dhaka that was depicted.

I understand it might be silly to split hairs over authenticity in a genre that is dominated by ghosts and goblins and hidden murderous cults, but what I'm trying to say is that when the masters of the genre write, they can work such outlandish material into the narrative in such a way that they feel completely natural and commonplace. An example of this would be William S. Burroughs' Cities of the Red Night (Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1981). This book has one of the most daring, outlandish plots and structures that I've ever had the pleasure of reading, but nothing, and I mean absolutely nothing, seems out of place.

This to me is the benchmark for work dealing with non-reality. This to me is the major strength of Apni Ki Alien Dekhte Chan—the debut collection of 15 loosely connected short stories by Wasif Noor. Not only do the stories feel like they could be real, but it feels like Noor has captured the zeitgeist of the period of 2010 itself.

Some of the tricks used to evoke this authenticity were so simple, they can be termed genius. The loose connection of the stories creates this shared reality through the book, and being immersed in this shared reality for the duration of around 100 pages builds a sense of relatability between the readers and the book. The way Noor repeatedly mentions the same objects/attributes of this shared reality—a Facebook group, an artist disappearing, the narrative of one story becoming background information in the next—gives a sense of actuality to this world, making it a world that seems to exist out of the confines of the stories themselves.

The use of the Facebook group was a particular standout. As a source of information, Noor repeatedly mentions a Facebook group for the sharing of 'real' paranormal incidents. This clever mirroring of the real world through the lens of fiction (for groups dedicated to the paranormal had become something of a hot topic for Facebook users in Bangladesh during the 2010s, particularly due to the re-popularisation of the paranormal due to Bhoot FM and Bhoutist) elicits strong reactions from the readers, and this simultaneously allows the readers to connect strongly with the narrative while evoking a sense of wonder and excitement, something that is important when confronting works of the unreal.

And this brings me to the second major strength of the book: how it evokes a sense of fresh wonder and excitement regarding the mysteries of the universe—something that was part of the zeitgeist before the internet became ubiquitous and we all became disappointed with the mundanity of the world. Or, to be more precise, it evokes a sense of childlike wonder that can only be experienced during one's childhood and adolescence, something that gets lost as the crushing mundanity of everyday life devours us whole.

And through the use of unique plot points, Noor definitely delivers on this sense of wonder he has elicited. The book starts out hackneyed enough, with the tale of a tall slender-man like ghost that waits for its victims under lampposts. But when suddenly an inexplicable, seemingly inexhaustible hole appears in a construction site one day and strange, otherworldly beings start pouring out of it, you know you are in for something special. I know that to readers of international literature, this is nothing new. Noor himself admits that the influence of weird fiction masters such as Lovecraft, and I fully admit that the stories themselves seem to be heavily inspired by the more iconic works of Junji Ito. But the way Noor fuses these elements into the Bangladeshi setting in such a fresh and authentic way renders such familiar monsters fresh and exciting.

Noor, furthermore, deepens this wonder by leaving many of his questions unanswered, and by using a shared reality, he paints a picture of Bangladesh that is at the same time familiar and unfamiliar, a Bangladesh that is material and a Bangladesh that is enticingly weird and exciting. By turning such a familiar landscape unfamiliar through the use of foreign concepts and monsters, and by deepening this sense of eeriness by repeatedly alluding to events from other stories that are either happening simultaneously or have already happened, Noor enlarges our sense of wonder, and paints a picture of a reality that is utterly fascinating. Even for a jaded, materialist 27-year-old like me, this took me back to my 12-14 year old self, as he sat in the balcony basking in the evening sun, wondering about all the weird and exciting things he would experience when he grew a bit older.

The characters of the book somewhat add to the experience, too. Unlike the characters of traditional Bangla horror stories, there is no appeal to religion in any of the pieces. The characters have a penchant for the weird and the eerie, and even though they get scared and suffer from anxiety, this curiosity leads them deeper into the dark mysteries they are confronted with, as if they were hypnotised.

Unfortunately, this is where the weakness of the stories starts to show. A complaint I have regarding Ito is that oftentimes, his characters appear exceedingly obtuse, putting themselves in situations where it should be apparent that there is going to be trouble. This could be solved by allowing readers glimpses into the thought-process of the characters, but Ito is usually concerned with the machinations of plots over character insight, and Noor suffers from the same problem. There are times when the characters make no sense; even though you get glimpses into the characters sometimes, in order for there to be true understanding, there needs to be more interiority. Noor could also have focused on fleshing out the characters a bit more. I understand that this is one of the pitfalls of genre fiction as a whole, but when I think back on the great works of fiction in this lineage (The Shining by King, for example), I can't help but remember that those works did have great characters. These are aspects that Noor should certainly work on, and this can be guaranteed to take his work to new heights.

On a similar note, Noor often switches between characters, but this isn't done seamlessly. It sometimes becomes difficult to understand which character is speaking, and readers have to do a bit of a double take sometimes. Yes, this is more on the editing of the book than the writing, but this brings me to the biggest flaw.

To say that the editing of the book is atrocious would be an understatement. There are barely any spaces or chapter breaks used to show the passage of time, and this results in a reading experience that is quite frustrating. There are no breaks to indicate POV shifts either. I don't think there was any story in the book without grammatical/structural errors or a malapropism dropping in out of nowhere. There were numerous spelling mistakes as well. A lot of this falls on the editors of the book (something the Bangla literary scene is notorious for), but Noor should have paid more attention himself, as sometimes it does feel like there was a lack of care on his part during the editing process as a whole.

I understand that the last two paragraphs should make it difficult to recommend this book. What Noor has done really well is construct a world that is enigmatic and enticing, a world that you repeatedly want to revisit (I had the idea to write this review after re-reading the book recently). His use of language (mostly) stands out against the crop of Humayun Ahmed imitators as well. But what Noon really needs to work on is improving his characters and editing.

But if you're like me, and you miss that sense of wonder that you used to be imbued with back when you were younger, then I say that this book is worth giving a shot. And it is precisely for that reason that I'll be observing Noor's career with great interest in the coming years. If he works on the issues I've mentioned, then there is a possibility he will be able to unveil a new dawn in the genre fiction market in Bangladesh, a dawn that could take the industry as a whole to new heights.

Nafis Shahriar is currently working in the Ed-Tech space.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments