B'baria Handloom Industry: Hanging by a thread

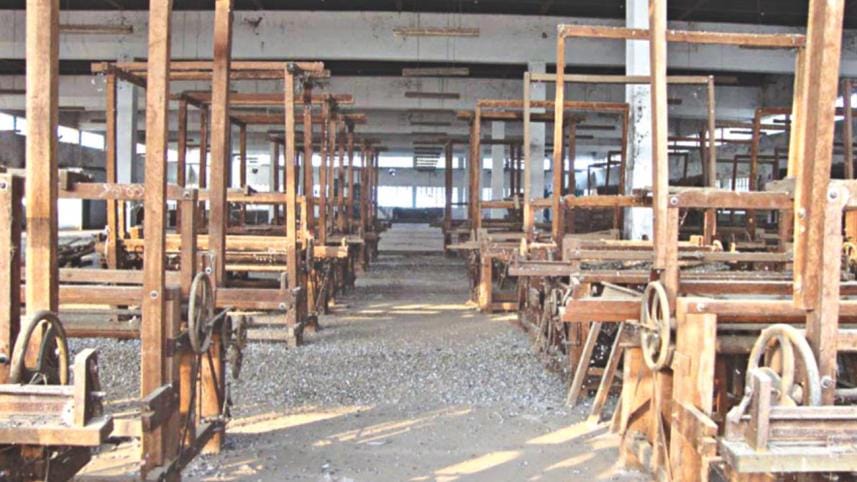

The once hustle and bustle of the traditional handlooms at Bancharampurupazila of Brahmanbaria is now a thing of the past.

Gone are the familiar clacking sound of handlooms and manual machines used to weave fabric. They are slowly disappearing along with the area's signature industry.

About 5,000 handlooms have been closed, leaving several thousand people unemployed. Many have long moved to other means of income such as farming.

According to officials at the Bangladesh Handloom Board, there were 9,162 handlooms in 32 villages in Bancharampur in 2005. At present only about 4,000 handlooms are in operation.

People of this area once took pride in the handmade lungi and gamcha they produced. But now, even skilled artisans discourage their heirs from taking this profession for the gruelling work and low pay.

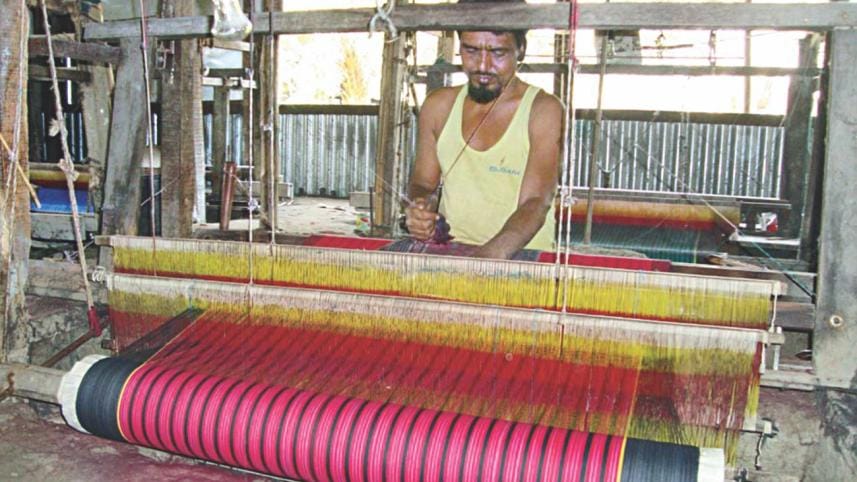

Most handlooms are family run businesses. They are set up in sheds behind people's houses.

These old-fashioned looms are a part of the landscape of the 32 villages. It continues to be a family occupation, using traditional methods of production and designs.

Settling down behind the wooden contraption strung with colourful spools, a weaver manoeuvres his arms and legs to bring the loom to life, thread by thread. They repeat this painstaking process for hours each day.

Hossain Mia of the Rupasdi village, who has been weaving since 1987, said wages were good when he first started. “Even if we are skilled, we cannot compete with the power looms. The market price of handmade lungi and gamcha should be higher as it is of higher quality.”

Competition over the years has increased in the textiles sector, particularly after the introduction of power looms that enjoy economies of scale.

On low productivity at the handlooms, Khasru Mia of the same village, who has been in the profession for 14 years now, said the job of weaving is monotonous and laborious.

“Workers are able to make lungi in full swing for half a month. They need to rest during the other half.”

“Three square meals are a far cry for us weavers, although showrooms in fancy malls sell these handmade lungi at very high prices as they are high in demand,” said Bakir Uddin, a weaver, as he pulls the brake lever on the handloom to take a break. “What first started as a hobby, later became a passion for me. I just wish I was better compensated so that we could live a more dignified life.”

The weavers' goods are transported by boat to Baburhat in Narsingdi; it is one of the biggest wholesale points of local fabrics in Bangladesh and just an hour's drive from the capital. Depending on quality, a small lungicosts Tk 50-60 while a larger one Tk 110 at the wholesale market.

Although there is good demand, the looms suffer from lack of capital, rising prices of dye and yarn and low wages.

Ohid-Uz Zaman, a weaver at Rupasdi village, said, “The cost to make four lungi has increased by Tk 80 owing to the price hike of yarn, but the selling price did not increase accordingly.”

On the other hand, a weaver can weave four lungis a day, for which he gets a mere Tk 120, he added.

Demanding government subsidies, the weavers said small to midsize handlooms will not sustain without proper financial support.

But to save this industry requires more. The government will have to curb the prices of raw materials for this sector and provide subsidies to import yarn.

Sanaullah Sunny, president of Salimabad Union Primary Weavers Association, said, “Most handloom owners of this area start business by taking out loans. A lion's share of the profit goes into the pockets of the lenders.”

With a rising number of weavers leaving the profession, there is a dearth of skilled manpower, which affects productivity. The government should take an initiative to give training to increase productivity, said Firoz Mia, chairman of Rupasdi Union Council. “This is an industry that directly relies on the skills of the weavers, so proper training is necessary.”

Siddiqur Rahman, president of Dariadaulat Weavers' Association, said the government can keep this heritage alive by making low-cost funds available for the sector. “Proper policy framework will ensure a bright future for the industry.”

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments