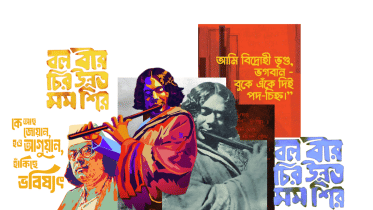

Like an undying phoenix, the spirit of Nazrul lives on

That night in December 1921, while his comrade Muzaffar Ahmed slept, Nazrul scribbled furiously. By the morning, the air was charged with something new. “Bolo Bir, Chiro Unnoto Momo Sheer…” (“I am the Rebel Eternal, / I raise my head beyond this world, / High, ever erect and alone!”) he declared. It was not merely the birth of a poem but of a cultural rupture. Critics would later see in “Bidrohi” a break from the ‘Rabindric’ serenity that had long defined Bengal’s literary landscape—a new current of words forged in fire, laced with the clang of rebellion.

26 August 2025, 18:05 PM

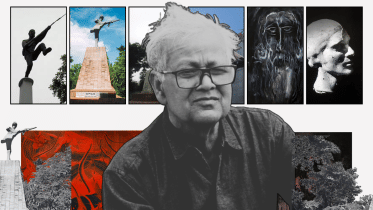

Remembering Hamiduzzaman Khan, the sculptor who shaped a nation’s memory

For decades, his works stood sentinel across the landscape of this country—quiet but powerful witnesses to our struggles, our resilience, and our history. “Sangsaptak”, perhaps his most defining piece, looms outside Jahangirnagar University’s central library like a frozen cry.

20 July 2025, 13:50 PM

July never ended, it’s an ongoing reality: Shayan

The artiste, whose lyrics and guitar immortalised the volatile, uncertain moments of the July Uprising through songs such as “Bhoy Banglay,” “Jonotar Beyadobi,” “Bhoy Banglay Bhoy,” “Ei Meye Shon,” “Rani Maa,” and “O Neta Bhai,” offered this correspondent a deeply personal glimpse into her creative process during a time when life seemed hollow and rebellion offered meaning.

18 July 2025, 18:05 PM

Brecht’s courtroom parable returns to Dhaka stage with Prachyanat’s 'Byatikrom O Niyom'

Set against a parched desert landscape, the play follows a paranoid merchant, a humble porter, and a local guide as they journey across unforgiving terrain in pursuit of profit and survival. A fatal misunderstanding leads to tragedy, unfolding into a courtroom drama that questions whether justice can truly be impartial when wealth and power dominate the rules.

16 July 2025, 07:00 AM

Shama Rahman and Afzal Hossain headline rain-drenched cultural evening

As Dhaka shimmered beneath days of rainfall, a quiet enchantment stirred inside the Sheraton Ballroom last Friday; however, this wasn't just another evening of performances. “Badol Diner Prothom Kodom Phul”, hosted by MW Magazine Bangladesh, unfolded more like a dream shared between memories and monsoon.

12 July 2025, 11:29 AM

A city gasps, a park resists: Panthakunja protest redefines civic action

Panthakunja, located on Sonargaon Road, was once a rare oasis in the capital

26 June 2025, 18:05 PM

Post-July Shilpakala: The cultural spearhead needs to change internal culture

More than just a home for the arts, it has long been a custodian of collective memory, responsible for shaping a culturally enriched, humane Bangladesh, rooted in its historical context. Despite its undeniable impact in preserving traditions, amplifying artistic expression, and cultivating national identity, the institution has long been a target for political manipulation, corruption, and political parties’ quests to control the cultural conscience of the country.

30 May 2025, 02:05 AM

Bangaliyana marches on

Pahela Baishakh heralds new beginning

14 April 2025, 07:20 AM

Thousands gather at Ramna Batamul to welcome Bengali New Year

Thousands of Bangalees ushered in Bengali Year 1432 at Ramna Batamul on Monday morning, as Chhayanaut’s iconic Pahela Baishakh celebration marked its 58th edition with renewed hope, harmony, and heritage.

14 April 2025, 02:53 AM

Chhayanaut ushers in 1432 at Ramna Batamul with Raag Bhairav

As the sun rose over Dhaka, Chhayanaut’s Pahela Baishakh celebration for the Bengali year 1432 began at Ramna Batamul. The theme of Chhayanaut's Pahela Baishakh celebration this year is "Amar Mukti Aloy Aloy" (my freedom lies in light). Through this theme, Chhayanaut aims to convey a message of hope, resilience, and renewal.

14 April 2025, 01:09 AM

The spirit of defiance and freedom fuels Pahela Baishakh

As the nation now stands on the cusp of renewal, Pahela Baishakh 1432 arrives at a time when the people of Bangladesh are eager to reclaim their cultural voice—seeking a deeper connection to its identity, heritage, and hope. For centuries, it has been an occasion of collective celebration, resilience, and unity.

13 April 2025, 18:03 PM

Pahela Baishakh: Chhayanaut all set for celebrations

Chhayanaut is all set to celebrate Bangla New Year, Pahela Baishakh, with its iconic cultural programme at Ramna Batamul in Dhaka.

11 April 2025, 19:48 PM

‘Cultural healing’ and ‘inclusivity’ key in Bengali New Year celebrations as Ministry announces plans

Farooki declared that this year’s New Year celebrations would bring together not just Bengali citizens, but also 27 ethnic communities from across the country. “Diversity is our most powerful and beautiful asset,” he said.

9 April 2025, 11:20 AM

Shilpakala is not without leadership: Mostofa Sarwar Farooki

Renowned filmmaker and cultural affairs adviser Mostofa Sarwar Farooki has dismissed concerns that Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy is running without leadership following the recent resignation of its Director General, Syed Jamil Ahmed.

9 April 2025, 09:14 AM

Violence on women is a byproduct of patriarchy: Shayan

Renowned musician and social activist Farzana Wahid Shayan, known for her bold stance on gender inequality and oppression, has once again raised her voice in response to the alarming rise of gender-based violence in Bangladesh. In recent weeks, a wave of brutal incidents, including the rape of eight-year-old Asiya by a relative, has sent shockwaves throughout the nation, prompting widespread outrage and calls for justice.

10 March 2025, 09:00 AM

Parsha wants to write her own destiny

Parsha Mahjabeen Purnee holds two very distinct identities among her audiences, one more intriguing than the other—she is a musician and now an actor with her (groundbreaking) debut in Jahid Preetom’s “Ghumpori”. A third-year university student who inspired millions through her song, “Cholo Bhule Jai” during the July Movement gets candid with The Daily Star about her journey, new-found fame and future aspirations.

7 March 2025, 18:05 PM

Theatre activists demand autonomy for Shilpakala, rally for Syed Jamil Ahmed's reinstatement

This rally, which brought together theatre artistes, writers, directors, designers, and cultural activists, came in the wake of the controversial resignation of Syed Jamil Ahmed, the Academy’s former director general. The procession aims to voice a clear and urgent demand for not only the reinstatement of Ahmed but also for the autonomy of Shilpakala Academy, free from bureaucratic interference.

2 March 2025, 11:46 AM

Nazrul Utsav 2025 opens with a message of unity and resilience

The much-anticipated annual Nazrul Utsav 2025 kicked off yesterday, celebrating the philosophies of Kazi Nazrul Islam, the national poet whose works embody a powerful message of secularism, humanity, and unity. The two-day festival, organised by the Bangladesh Nazrul Sangeet Songstha (BNSS) at the Chhayanaut premises, is scheduled to run from 5pm to 9:30pm, featuring performances by over 100 artistes from Bangladesh.

25 February 2025, 11:16 AM

‘It came as a surprise to me’

Eminent Bangladeshi artist and creator of the iconic "Tokai"character, Professor Rafiqun Nabi, was denied access to the stage at an art exhibition at the Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Dhaka. The event, held yesterday, was meant to celebrate and showcase the talents of emerging artists from the university's Department of Drawing and Painting. However, what unfolded left many questioning the university’s priorities.

18 February 2025, 19:53 PM

The enduring legacy of Ustad Zakir Hussain

In a career that spanned over six decades, Zakir Hussain worked with not just India’s musical stalwarts like Pandit Ravi Shankar and Ustad Ali Akbar Khan but also legends like George Harrison and Van Morrison.

16 December 2024, 13:27 PM