Politics of School Examinations

In 2009, the government introduced the Primary Education Completion Examination (PECE), a mandatory test for grade 5 students to certify completion of the primary cycle. PECE results marked a dramatic increase in the completion rate. By mid-2000s, enrolment rates in Bangladesh were above 90 percent but, prior to 2009, many children dropped out, and the completion rate was only about 50 percent. By 2015, completion reached about 80 percent, where it has remained since. Among students who attend the PECE, over 95 percent achieve at least a basic pass.

If we stop here, it may seem as if Bangladesh has achieved near-universal primary education. But what does an 80 percent completion rate, or 95 percent PECE pass rate, mean in terms of learning?

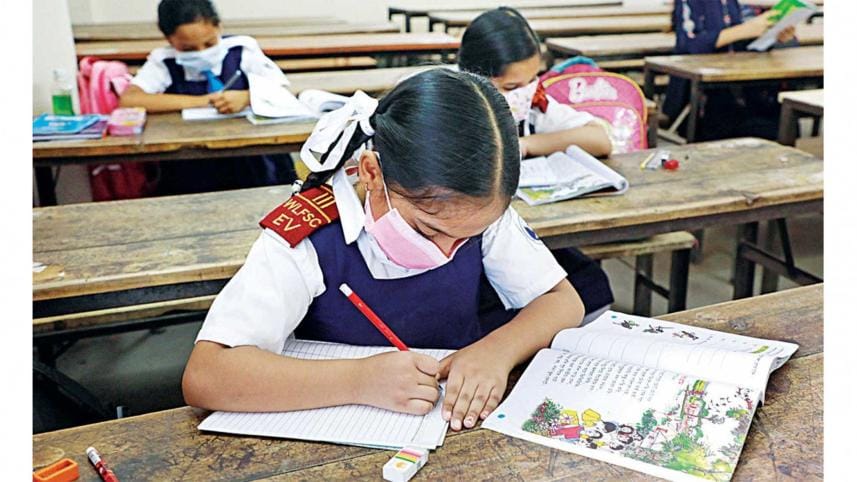

One source of evidence is a 2015 study undertaken by Nath and colleagues, who expressed concern that PECE is making primary school too "exam-centric". Teachers are "teaching to the test". Parents have increased payments for private tutoring, usually undertaken by the students' teachers. In the study's survey, the average expenditure per student on PECE-related activities was over Tk 8,000. Most of it was spent on private tutoring. Other major expenditures were for school-organised coaching and PECE guide books.

Another source of evidence arises from the World Bank's simple "learning poverty" index. The index estimates the share of children aged 10-14 who cannot read at a basic level. The index is calculated as the sum of two groups: 1) children out of school assumed unable to read; and 2) children in school at grade 5 but unable to read at a basic level. In Bangladesh, about 20 out of 100 children aged 10-14 are not attending school. Among the 80 children attending school, about half are able to read at a basic level. Overall, in Bangladesh, the estimated "learning poor" are 58 percent of the total. The percentages of learning poor in India are 55 percent and in Pakistan 75 percent. By contrast, in Sri Lanka, only 15 percent are learning poor.

The implication of the learning poverty index is depressing: many children achieve a PECE pass rate but cannot read. Sceptics may argue that the learning poor index is inaccurate. A check on the index is the National Student Assessment (NSA), a survey conducted by the Directorate of Primary Education every two years. This survey assesses large samples of children in primary school on their ability to read Bangla and do basic arithmetic. Unfortunately, the results prior to 2009 are not comparable with more recent results. The surveys conducted in the 2010s are comparable and show only minor change from 2011 forward. For example, in the 2017 NSA survey, 56 percent of students in grade 5 were at the "basic" or "below basic" level. The NSA definition of "basic" is that students "can read some grade-appropriate words and short, easy sentences with hesitation and errors; can read aloud a grade-appropriate text slowly and with errors." The NSA defined the "desirable" level to be students above basic in both reading Bangla and mathematics. Obviously, the NSA did not assess children out of school. The more-or-less equivalent "learning poor" estimate based on the NSA result is 65 percent.

Clearly, learning has never been a top government priority in Bangladesh or elsewhere in South Asia (other than in Sri Lanka and a few Indian states). Political leaders focus on school enrollment, the number of teachers recruited and schools constructed, and the free textbooks printed and distributed. But requiring students to spend five years in primary school and not acquire the foundational skills of reading and mathematics is a betrayal of the children and their families. A business-as-usual approach will not solve our learning crisis, which was compounded by the long Covid-induced school closure. A learning recovery and remedial approach to help students acquire the essential foundational skills was thus essential even before the pandemic—it has become more urgent now.

The good news is that politicians, if they place high emphasis on school learning outcomes, can make significant improvements, even in neighbourhoods where children's families have few books and many parents are illiterate. For example, in India, the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) has governed the state of Delhi for nearly a decade. In recent years, secondary school results in government schools there have exceeded private school results, which was unthinkable a decade earlier.

The government of Bangladesh should, therefore, take effective measures to ensure that all children have enough interesting books to read, that children are encouraged to read, and that the schools are clean. A supply of textbooks and clean schools alone are not enough. Teachers play a crucial role. They should be well-trained and able to promote learning. They should not serve as "vote banks" at times of elections. Also, the current time-on-task in primary school is not enough. Adding more teaching time may be politically sensitive, but improvements require a convergence of priorities among the major groups involved including politicians, education officials, teachers, and parents.

In a recent press conference, the state minister for primary and mass education was unable to say whether they would abandon PECE this year. He concluded by saying they would revisit the plan later. This indecisiveness does not help. Perhaps, they do not have the power to scrap the PECE yet. But it's important that we acknowledge the importance of overcoming the learning loss caused in the past two years.

Shahidul Islam is an education policy researcher.

John Richards is a professor at the School of Public Policy, Simon Fraser University, Canada.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments