Development and political leadership: China’s Wang Huning and new perspectives

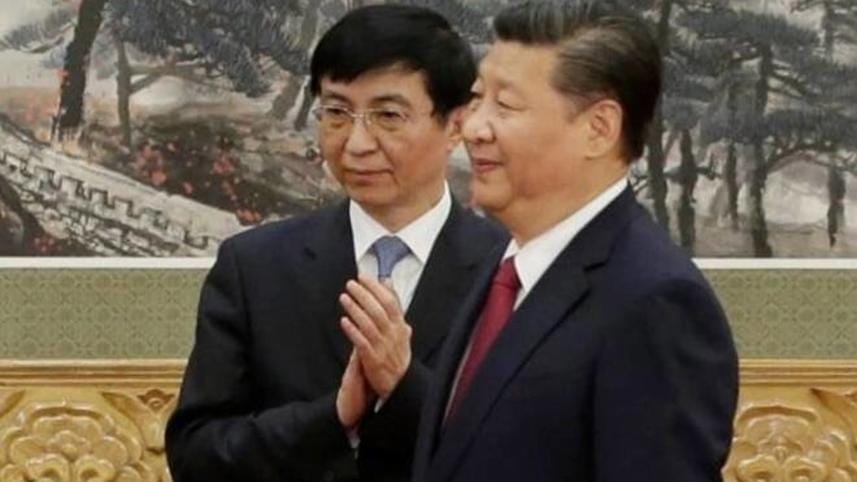

We have all become accustomed to the economic story of China, its astonishing success in reducing poverty, its emergence as the economic powerhouse of the 21st century and its infrastructural ambitions expressed through the Belt and Road Initiative. Lesser known is its foray into the world of ideas and political theorising. Few people in Bangladesh may have heard of Wang Huning. The political theorist behind three paramount leaders including the current leader Xi Jinping, Wang Huning's induction into the all-powerful Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party marks the first time a person primarily from the world of ideas has been assessed as important for the corridors of supreme power.

Born in Confucius' birthplace, Shandong, Wang Huning's rise from being a professor of international politics at Fudan University in Shanghai has not merely been a personal journey. Seen by some international circles as China's Machiavelli, his theoretical constructs of political leadership during the modernisation process and integration of Confucian thoughts represent serious challenges to established theoretical orthodoxies on the interface of politics and development. They also provide a novel opportunity to take a fresh look at issues of governance, politics and development, which are particularly pertinent for countries like Bangladesh that are aspiring to climb the next rung on the development ladder.

The linking of democracy and governance to issues of developmental performance has long antecedents but in recent times has had varied and contested formulations. The coming to prominence of the "good governance" paradigm in the 1990s has obscured a deeper discourse on the interface of politics and development that has run since post-colonial developing countries grappled with issues of economic and political modernisation in the new world order following the Second World War. The late Harvard icon Samuel P Huntington's 1968 seminal work Political Order in Changing Societies provided a dominant reference point for this discourse. Huntington provided a reality check on the over-optimistic modernisation theories and pointed to the possibilities of political decay as much as political development in the process of social and economic change. Analysts and academics have had to cross the traditional disciplinary boundaries to grapple with such complexities, in the process bringing to prominence newer disciplines such as political sociology, institutional economics and culture studies.

A critical insight emerging from such analysis is that it is less the form of government and more the degree and quality of politics and governance (i.e. legitimacy, opportunities for contestations, rationalisation of authority, state capacity, robust spaces for public discourse, minimising system disruptions around transitions in power) that distinguish politically developed societies from politically decaying ones. Clearly, politics and development are closely intertwined processes that have no easy or predictable answers on cause and effect. Experience shows that there are both well-performing and poorly-performing "democracies". The more relevant issue thus is less the regime type per se or a normative set of "good governance" indicators, but rather the constellation of system and process features that generate a "political governance" capable of nurturing inclusive and sustainable economic outcomes.

Prevailing perspectives on democracy and governance in developing countries have a typical blind spot as to how politics and political leadership is accommodated within such analysis. For example, the "good governance" paradigm favoured by civil society and development agencies includes a politics variable—"political instability and violence". This is certainly relevant for many contexts. But what of realities such as today's Bangladesh, where there is both enforced political calm and pronounced uncertainty about the future—a case of "uncertainty despite stability" reflected, for example, in stagnant private investment, and rising brain-drain and youth unemployment? Similarly, the "democracy" discourse too has found it hard going to concretise the "politics" variable beyond "elections". The sad reality of "electoral democracies" across many parts of the developing world is either of "voter-less elections" or various degrees of "controlled" elections or directionless blood-letting by rival political blocs during transition. The economic and social fallouts in these countries are all too visible—all-encompassing corruption, state capture by elite groupings, deepening inequalities, pervasive insecurity, and political marginalisation of the common citizenry.

The pandemic has created an existential moment for humanity. Sadly, facile talk of "common purpose" is belied by the reality of vaccine inequality between developed and developing worlds, rise in number of billionaires and millionaires during the pandemic, and the misery of the "new poor". Clearly, the driving of "common purpose" has to start at home. And home here is the nation-state and the political order on which it functions. Fifty-odd years after Huntington penned his seminal work and the intervening rise and fall of neoliberal hubris of market supremacy, the development discourse is needing to embrace the thorny discourse of "politics".

It is here that Wang Huning and China's burgeoning discourse on political theory present new points of departure for the interface of development and political leadership. The impetus for rethinking came in the wake of the ideological crisis of communism, symbolised by the fall of the Berlin Wall. Wang Huning was the driving force for an ideological repositioning that also drew on Confucian thinking to project new concepts such as political meritocracy, virtuous governance and performance legitimacy. Such theoretical efforts have not necessarily led to a full-blown ideological construct such as liberal democracy. Nor have they gained broad-based endorsement. But they have certainly put a spotlight on the urgency of seeking new answers to the all-too-familiar problems of democratic dysfunction and political decay in many of the developing countries. How can merit and efficiency be nurtured as integral building blocks of political governance? And is "merit" enough without a commitment to values and being open to performance scrutiny? The discourse is notably reticent on issues of representation, focusing instead on the issue of legitimacy.

From an external perspective, these are large canvases worth exploring with lessons to be independently arrived at rather than axiomatically drawn. Whatever such instrumental lessons turn out to be, the discourse lesson is already clear. Without "good politics", there will not be "good development". Unlike "good governance", which has over-focused on technical solutions, "good politics" forged on values, vision and competence can only emerge out of risk-taking and active engagement.

Hossain Zillur Rahman is Executive Chairman, Power and Participation Research Centre (PPRC) and former Advisor of the Caretaker Government of Bangladesh. Email: hossain.rahman@gmail.com

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments