Globalisation

What is the future of globalisation?

The future of globalisation hinges less on market logic than on political will.

29 May 2025, 07:00 AM

Our world is becoming economically fragmented

Even though globalisation may have peaked, it is far from being wholly reversed, and Western countries need to stop weaponising trade and economic policy.

19 February 2023, 02:00 AM

The Next Globalisation

Developments in three areas – telework, renewables, and AI – will bind countries together in new networks of interdependence.

27 January 2023, 10:24 AM

The irreversibility of globalisation

Politicians, media commentators, and economists have been far too hasty in predicting the demise of globalisation.

9 September 2022, 02:00 AM

Getting Deglobalisation Right

The World Economic Forum’s (WEF) first meeting in more than two years was markedly different from the many previous Davos conferences.

2 June 2022, 18:00 PM

Why we need globalisation

From the Brexit vote to Donald Trump's election as US president to rising support for populist parties in countries like Germany and Italy, much of the electoral upheaval in Western democracies in recent years has been attributed at least partly to a backlash against globalisation. But globalisation does not deserve voters' ire.

18 May 2018, 18:00 PM

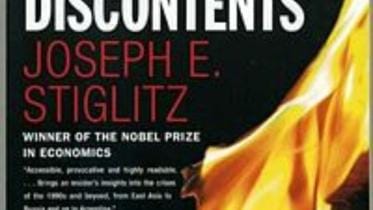

The globalisation of our discontent

Fifteen years ago, I published Globalization and Its Discontents, a book that sought to explain why there was so much dissatisfaction with globalisation within the developing countries.

11 December 2017, 18:00 PM

The new socialism of fools

According to standard economic theory, redistribution only comes about when a country's exports require vastly different factors of production than its imports. But there are no such differences in today's global economy.

13 August 2017, 18:00 PM

Globalisation and its new discontents

The failure of globalisation to deliver on the promises of mainstream politicians has surely undermined trust and confidence in the “establishment.” And governments' offers of generous bailouts for the banks that had brought on the 2008 financial crisis, while leaving ordinary citizens largely to fend for themselves, reinforced the view that this failure was not merely a matter of economic misjudgments.

7 August 2016, 18:00 PM

From the frying pan to the fire?

If the last two centuries were of inconclusive and asymmetrical globalisation, the present one deserves to be called the century of migration.

28 January 2016, 18:00 PM