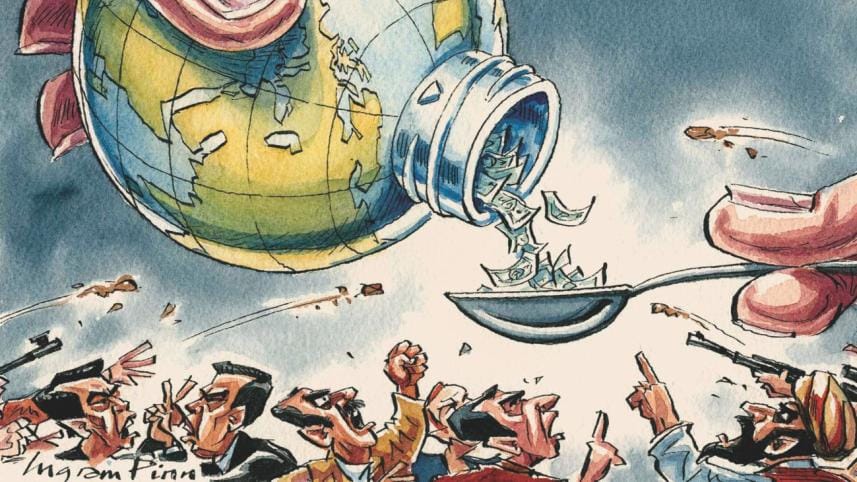

The globalisation of our discontent

Fifteen years ago, I published Globalization and Its Discontents, a book that sought to explain why there was so much dissatisfaction with globalisation within the developing countries. Quite simply, many believed that the system was "rigged" against them, and global trade agreements were singled out for being particularly unfair.

Now discontent with globalisation has fuelled a wave of populism in the United States and other advanced economies, led by politicians who claim that the system is unfair to their countries. In the US, President Donald Trump insists that America's trade negotiators were snookered by those from Mexico and China.

So how could something that was supposed to benefit all, in developed and developing countries alike, now be reviled almost everywhere? How can a trade agreement be unfair to all parties?

To those in developing countries, Trump's claims—like Trump himself—are laughable. The US basically wrote the rules and created the institutions of globalisation. In some of these institutions—for example, the International Monetary Fund—the US still has veto power, despite America's diminished role in the global economy (a role which Trump seems determined to diminish still further).

To someone like me, who has watched trade negotiations closely for more than a quarter-century, it is clear that US trade negotiators got most of what they wanted. The problem was with what they wanted. Their agenda was set, behind closed doors, by corporations. It was an agenda written by and for large multinational companies, at the expense of workers and ordinary citizens everywhere.

Indeed, it often seems that workers, who have seen their wages fall and jobs disappear, are just collateral damage—innocent but unavoidable victims in the inexorable march of economic progress. But there is another interpretation of what has happened: one of the objectives of globalisation was to weaken workers' bargaining power. What corporations wanted was cheaper labour, however they could get it.

This interpretation helps explain some puzzling aspects of trade agreements. Why is it, for example, that advanced countries gave away one of their biggest advantages, the rule of law? Indeed, provisions embedded in most recent trade agreements give foreign investors more rights than are provided to investors in the US. They are compensated, for example, should the government adopt a regulation that hurts their bottom line, no matter how desirable the regulation or how great the harm caused by the corporation in its absence.

There are three responses to globalised discontent with globalisation. The first—call it the Las Vegas strategy—is to double down on the bet on globalisation as it has been managed for the past quarter-century. This bet, like all bets on proven policy failures (such as trickle-down economics) is based on the hope that somehow it will succeed in the future.

The second response is Trumpism: cut oneself off from globalisation, in the hope that doing so will somehow bring back a bygone world. But protectionism won't work. Globally, manufacturing jobs are on the decline, simply because productivity growth has outpaced growth in demand.

Even if manufacturing were to come back, the jobs won't. Advanced manufacturing technology, including robots, means that the few jobs created will require higher skills and will be placed at different locations than the jobs that were lost. Like doubling down, this approach is doomed to fail, further increasing the discontent felt by those left behind.

Trump will fail even in his proclaimed goal of reducing the trade deficit, which is determined by the disparity between domestic savings and investment. Now that the Republicans have gotten their way and enacted a tax cut for billionaires, national savings will fall and the trade deficit will rise, owing to an increase in the value of the dollar. (Fiscal deficits and trade deficits normally move so closely together that they are called "twin" deficits.) Trump may not like it, but as he is slowly finding out, there are some things that even a person in the most powerful position in the world cannot control.

There is a third approach: social protection without protectionism, the kind of approach that the small Nordic countries took. They knew that as small countries they had to remain open. But they also knew that remaining open would expose workers to risk. Thus, they had to have a social contract that helped workers move from old jobs to new and provide some help in the interim.

The Nordic countries are deeply democratic societies, so they knew that unless most workers regarded globalisation as benefiting them, it wouldn't be sustained. And the wealthy in these countries recognised that if globalisation worked as it should, there would be enough benefits to go around.

American capitalism in recent years has been marked by unbridled greed—the 2008 financial crisis provides ample confirmation of that. But, as some countries have shown, a market economy can take forms that temper the excesses of both capitalism and globalisation, and deliver more sustainable growth and higher standards of living for most citizens.

We can learn from such successes what to do, just as we can learn from past mistakes what not to do. As has become evident, if we do not manage globalisation so that it benefits all, the backlash—from the New Discontents in the North and the Old Discontents in the South—is at risk of intensifying.

Joseph E Stiglitz is the winner of the 2001 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences. His most recent book is Globalization and its Discontents Revisited: Anti-Globalization in the Era of Trump.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2017.

www.project-syndicate.org

(Exclusive to The Daily Star)

Comments