enforced disappearances

‘We’ll always stand by you’

He added that any democratic government has an obligation and responsibility towards the victims and their families.

18 January 2026, 00:00 AM

Enforced disappearances: Rab complicit in 25% cases

The Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances has recommended extensive institutional and legal reforms to end enforced disappearances and human rights abuses, including disbanding the Rapid Action Battalion, the worst offender.

5 January 2026, 18:00 PM

The state must shun the machinery of erasure

Report on enforced disappearances reveals systematic political purges.

5 January 2026, 13:03 PM

Enforced disappearances: 10 army officers brought to ICT

The tribunal is scheduled to hold hearing on charge framing against 17 accused

3 December 2025, 04:54 AM

From hope to disillusion: Human rights abuses under the interim government

Although the interim government has repeatedly stated that it opposes mob violence, its actions have not reflected a serious commitment.

24 November 2025, 03:00 AM

ICT sends 15 army officers to jail

For the first time in Bangladesh’s history, 15 army officers were taken to a civil court yesterday to face trial for their alleged role in enforced disappearances under the Awami League regime and killings during the July uprising.

22 October 2025, 18:09 PM

Extrajudicial killings: Ex-Rab men give chilling accounts of Ziaul’s role

The Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances with the support of the cultural ministry produced a documentary titled “Unfolding the Truth” in which former Rab officers directly implicated Maj Gen Ziaul Ahsan.

8 October 2025, 22:32 PM

Haunted by scars, still waiting for justice

Survivors of enforced disappearances broke down yesterday as they recalled the torture, humiliation, and threats they endured in secret detention centres.

29 August 2025, 18:19 PM

2 years lost, life shattered

He was around 15 when he was picked up, a ninth grader.

15 June 2025, 19:20 PM

Joint Interrogation Cell evidence destroyed after August 5

Evidence of “Aynaghar” was destroyed even after August 5, 2024, to hide the complicity of the Directorate General of Forces Intelligence (DGFI), said the commission investigating enforced disappearances in its report to Chief Adviser Muhammad Yunus.

20 January 2025, 18:00 PM

Enforced disappearances: ‘Hasina herself was involved’

Former prime minister Sheikh Hasina, her defence adviser Maj Gen (retd) Tarique Ahmed Siddique, former director general of the National Telecommunication Monitoring Centre Maj Gen Ziaul Ahsan, and senior police officers Monirul Islam and Md Harun-Or-Rashid were all involved in enforced disappearances.

14 December 2024, 18:22 PM

Try Hasina, Awami League

Families of the victims of enforced disappearances, extrajudicial killings, and those martyred and maimed in the July mass uprising yesterday demanded that ousted Sheikh Hasina and her party be brought to book.

10 December 2024, 20:29 PM

Mayer Daak gathers victims of various injustices at Int'l Human Rights Day rally

Many victims injured in the July uprising, including those who lost their eyes or other body parts, also attended the rally.

10 December 2024, 08:53 AM

Rab must be rebuilt from the ground up

But without political reforms, any change risks being superficial

13 November 2024, 15:14 PM

Enforced disappearances: Yunus pledges full support to probe body

Commission receives 1,600 complaints so far

9 November 2024, 16:00 PM

Enforced disappearances: Inquiry commission finds 8 detention centres

The inquiry commission on enforced disappearances found eight secret detention centres in Dhaka and its surrounding areas.

5 November 2024, 19:40 PM

Where are our loved ones?

Ayesha Ali has been praying every day for over 10 years to see her son.

30 August 2024, 18:00 PM

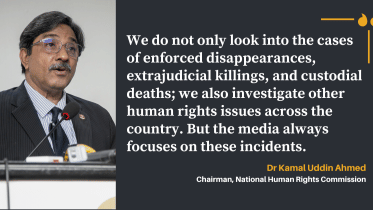

‘NHRC can’t directly investigate cases involving law enforcers’

NHRC Chairman Dr Kamal Uddin Ahmed talks about how the commission has dealt with the cases of enforced disappearance.

30 August 2023, 01:00 AM

Enforced disappearances: UN group records 5 more cases

Five new incidents of enforced disappearance in Bangladesh were reported to the UN Working Group on Enforced Disappearances in the last one year.

17 September 2022, 18:00 PM

‘Expatriate Diplomacy’ and ‘Mercenary Columnists’

Government decision to engage in expatriate diplomacy to tackle negative propaganda raises a lot of questions.

17 September 2022, 15:00 PM