Back to the roots: Deshi décor finds new life in modern homes

Walk into a newly renovated apartment or café in Dhaka, and chances are, you'll spot a cane chair by the window, a nakshi kantha throw draped over a couch, or a cluster of earthenware lining the shelves. These aren't just aesthetic choices, but rather markers of a broader cultural shift. As global design trends begin to blur into one another, a growing number of Bangladeshis are turning inward, rediscovering local craft traditions and bringing them into contemporary interior design.

But what's fuelling this revival of deshi décor elements in modern spaces? And what does it say about our relationship with heritage, memory, and identity?

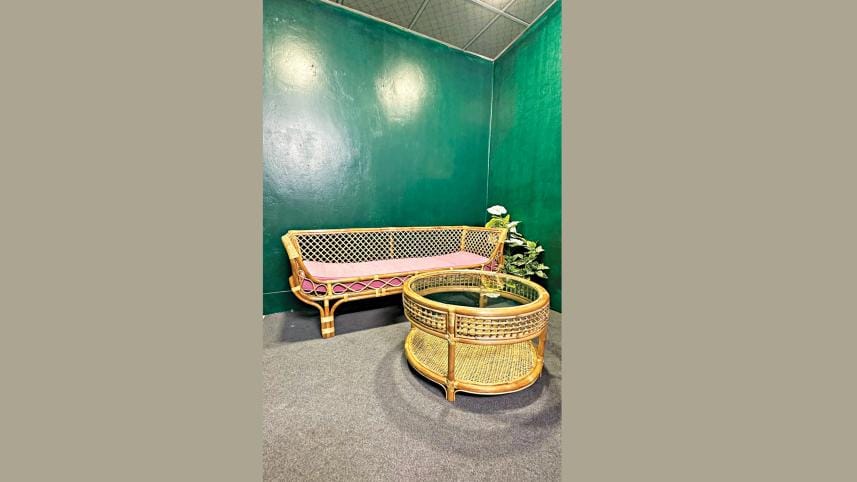

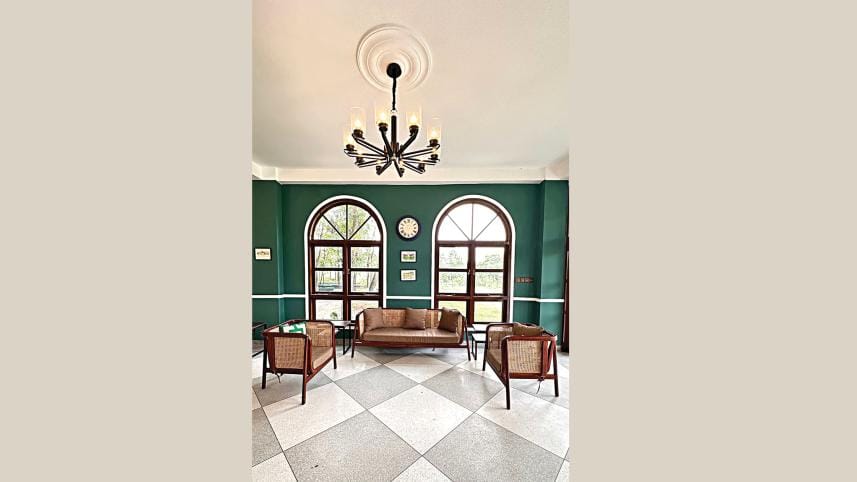

The return of cane

Cane furniture, lightweight, breathable, and built to last, was once a staple in Bangladeshi homes and tea stalls. Over the years, it was slowly replaced by heavier, imported options. Today, however, cane is enjoying a second life – this time, with a modern twist.

"Presently, hybrid models are popular among customers, which include the blending of wood and cane," says Ashik Hossain, Proprietor of Cane House. "Not only homeowners, but architects and restaurateurs are using tables, chairs, almirahs, and sofas made from cane and wood."

Cane furniture offers both style and sustainability, attributes increasingly sought after by conscious consumers. "Cane is an eco-friendly product," says Farhana Sharmin Hossain, proprietor of Troyee Cane Furniture Mart. "Clients prefer it because it's lightweight and moderately adjustable, unlike heavy sofa sets or tables."

But beyond its environmental value, cane furniture is also incredibly adaptable to modern living conditions. "This type of furniture is fully customisable," Ashik adds. "As apartments in Dhaka are smaller and space is limited, clients can customise the furniture in any way they want – from the size to the colour of the fabrics."

Popular pieces like the babui dolna – or cane swing chair – are also making a comeback, especially among younger buyers looking for statement pieces that double as cosy reading nooks or Instagram-worthy corners. "The cane swing chair is becoming increasingly popular," notes Farhana. "Along with it, customers are buying trays, tables, and different showpieces such as lamps."

Nakshi Kantha – From heirloom quilt to wall art

For generations, nakshi kantha was more than just a quilt – it was a canvas for rural women to stitch their thoughts, stories, and everyday surroundings into layers of recycled cloth. In modern design, this narrative tradition is being reinterpreted into striking visual elements.

Arifa Malik Bristy – CEO and architect of Irenderer – believes that deshi crafts like nakshi kantha are "not just decorative accents – they are part of our design DNA." In one of her own interior projects, she used Jamdani fabric as a soft screening element between seating areas. "It wasn't just a visual accent, it added a poetic layer of transparency and movement, handcrafted in a way no machine could replicate."

Younger designers like Bristy are now co-creating with rural artisans to produce kantha work that feels rooted yet innovative. The result is a fusion of heritage and modernity, rich in story and relevant in design.

Clay Pottery: The earth beneath our homes

Bangladeshi clay pottery is as old as its riverbanks. But what once sat in kitchen shelves as a humble matir handi is now being curated as sculptural home décor.

In one of her most memorable projects in Dhanmondi, Bristy even built an entire wall using hand-thrown clay pottery. "It introduced raw texture and a sense of rootedness that grounded the space," she shares.

Artisans from Rajshahi and Bogura are now seeing renewed interest in their traditional skills. Urban retailers are sourcing directly from potters, while workshops and DIY pottery sessions are introducing Dhaka's youth to the slow art of working with earth.

From terracotta lamps to matte-finish vases, clay elements are becoming essential to homes that seek a warm, minimalist aesthetic, balancing clean lines with earthy undertones.

Why deshi, why now?

The resurgence of deshi décor isn't just a design movement – it's an assertion of identity. In an increasingly homogenised world, traditional Bangladeshi crafts offer texture, history, and meaning that factory-made items often lack.

This revival also taps into a growing ethos of sustainability and ethical consumption. Choosing handmade over mass-produced, local over imported, is as much a lifestyle statement as it is an aesthetic choice.

These décor choices aren't just trends. They're proofs of craftsmanship, of community, and of care. And they remind us that sometimes, the most modern thing we can do is to look back, then build forward.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments