The postal tax that helped millions

For netizens of the time, postage stamps are mere remnants of history. Almost every Bangladeshi, 30 and above, will recollect fond memories of this collecting pursuit and their prized stamp album, but to the younger generation philately no longer bears any special meaning.

Ever since the first stamp was issued in England on May 1840, collectors focused only on the stamp itself – their design, the printing technology of production and particularly, on errors and flaws that were inadvertently made at the press. From the late 19th century, some discerning collectors started focusing on the postmarks and the markings on envelopes the stamps are stuck to.

In those early years of development of communication, postal charges varied depending on the weight of the article and the route they were travelling. Over decades, this approach of collecting became formally known as 'postal history.' Although 'traditional' and 'postal history' approaches still dominate philately, a recent off-shoot of postal history has become trendy – tracing social and political history of a time or a nation through the activities of the post office.

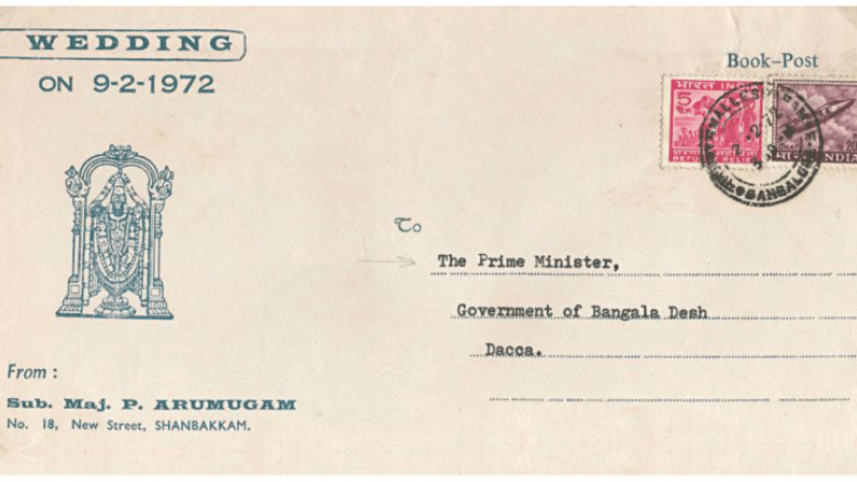

Considerable attention has been given in print, and recently on the Bangladeshi electronic media, on the first set of stamps issued by the Mujibnagar government in exile. These eight stamps issued on 29 July, 1971 acted as tiny ambassadors of the country and played a major role in garnering support for the cause of Bangladesh.

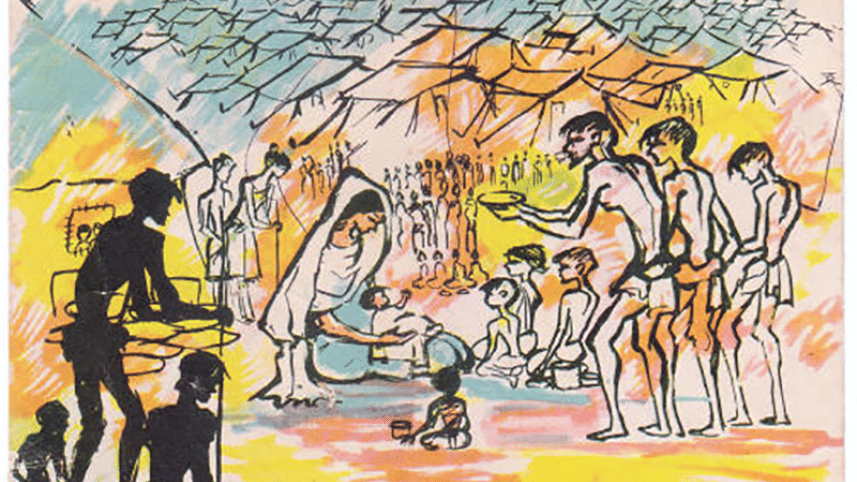

Little, however, has been written on other aspects of philately that are testament to that turbulent time. The genocide, and the plight of over 10 million refugees who sought sanctuary in neighbouring India, shook world conscience. People across the globe extended their hands in assistance and initiatives like the Concert for Bangladesh further established our just claim for freedom. But considering the colossal resources required to address the refugee crisis, these were insufficient.

India's assistance in our struggle for independence is well-documented. However, the important role of the Indian Post Office in generating funds for the refugees has remained unrecognised, and quite unfortunately so, even in philatelic circles! By October 1971, six months into the conflict and the Indian economy now crippled by the severity of the situation, steps were taken to reschedule prevalent taxation schemes and introduce a new levy altogether – the Refugee Relief Tax (RRT).

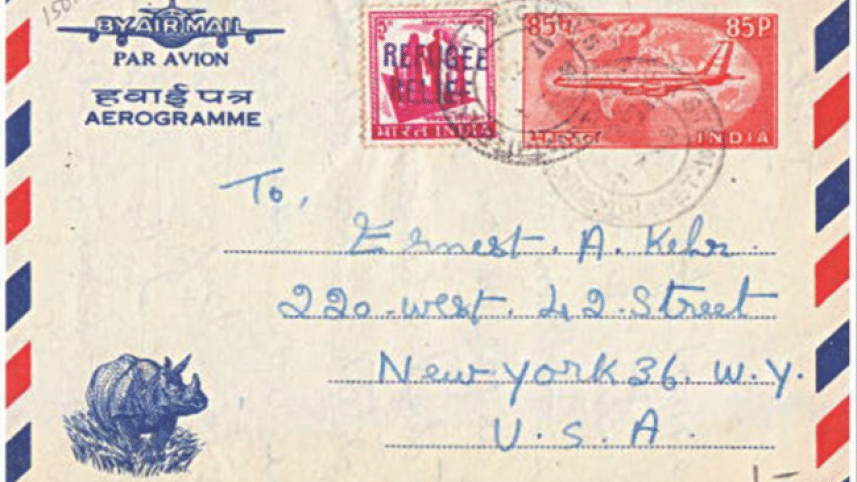

Between November 15, 1971 and March 31, 1973 a five paisa 'tax' payable by affixing a special stamp to postal articles – public and government – was made compulsory. A further 10 paisa tax was imposed on all contracts that normally needed stamp duty to be paid. Over a period of about 16 and half months, the taxation policy underwent several changes to meet the demands of time and gave rise to one of the most complex puzzles of 20th century philately.

The Refugee Relief was predominantly a postal tax, which refers to using a stamp for raising revenue for a purpose, and historically they have been used to collect funds to aid war efforts. Their use is mandatory for the processing of the postal article and their non-inclusion, subject to a further penalty. Compared to other forms of duty, postal tax has a multitude of advantages. As the levy is usually small (the RRT was just five paisa, or ten paisa in case of fiscal instruments), the response from the general public is not apprehensive; and for a country like India–with an extensive postal network and millions of postal articles being transmitted every day–the prospect of recuperating the targeted amount was feasible even within a very short time.

To put matters of the refugee crisis and the introduction of the tax in context, one must look back at the events of 1947 when the subcontinent was divided into India and Pakistan. Political and economic disparity gave rise to resentments in the Eastern wing of Pakistan, which, in just 24 years, culminated into a demand for sovereignty.

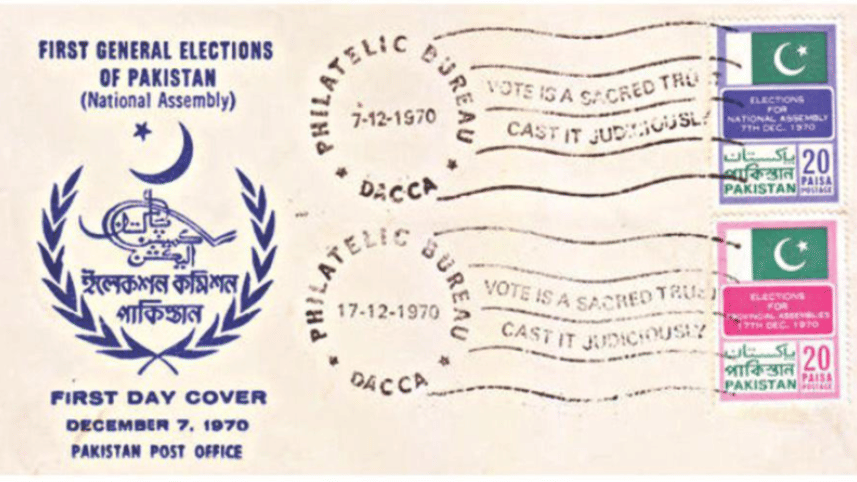

On December 7, 1970 the first general election of Pakistan at the federal level was held. The Awami League bagged 167 out of 169 seats allotted to East Pakistan in the National Assembly, the strength of which was 313. Even after securing absolute majority, the Awami League was not allowed to form government. Further talks took place at the highest level to bring about a solution to the apparent stalemate but on March 25, 1971 the West Pakistan army engaged in a brutal onslaught on Bengali civilians and military/paramilitary forces of the erstwhile East Pakistan. Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was arrested; a section of the prominent Awami League leaders escaped capture, crossed the border and eventually formed the Mujibnagar government in exile. Inside East Pakistan, a section of the population rebelled and as soon as the declaration of independence was made, Bengalis were at war!

Within a few days of the onslaught, cross border movement by refugees was noted at the highest level. On March 29, 1971, in a correspondence to Sadruddin Aga Khan, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), FL Pijnacker Hordijk, the representative in India, warned of an imminent global refugee crisis. Even such early cautionary responses failed to predict the scale of the mass exodus. The people and the government of India had from the early days of the conflict empathised with sufferings of the population of East Pakistan. Since the start of the conflict, the diplomatic position of India to the exodus was clear; although borders remained open on humanitarian grounds, they would under no circumstances allow the refugees to settle in the country.

Samer Sen, Permanent Representative of India at the United Nations, met Secretary General U Thant on April 23, 1971, and requested international aid. Subsequently, between April 26-27, Sadruddin Aga Khan of the UNHCR met with Secretary General U Thant at Berne, Switzerland to discuss the situation. In order to seek a peaceful, humanitarian solution to the problem, the UNHCR was entrusted with the role of general coordinator. In May 1971, a team visited several camps located in the Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura and Assam–the regions that had experienced the highest insurgence of refugees. It held talks with authorities, other United Nations agencies and non-government organisations in order to prepare a work plan, ensuring that the different agencies provide a coordinated effort towards a common goal. The end result, however, failed to yield any significant result. The Indian federal government now had no alternative but to bear the bulk of the expenses. The task of hosting the refugees fell almost entirely upon local and national governmental agencies with some support from India's civil society.

The events of 1971-72 were of far-reaching significance for the Indian economy and had a profound effect on the budgetary developments both in 1971-72 and 1972-73. The combined revised estimates of the budgetary transactions of the central and state governments for 1971-72 reveal that the gap between total outlay and current revenues turned out to be of the order of Rs. 2839 crores as compared to the original budget expectation of Rs. 2192 crores. By October 1971, faced with a burden of managing over a million people in various refugee camps, the Indian government made significant alterations to its taxation policy, and revised and introduced new taxes to recoup at least a part of the cost incurred, and facilitate further help to the refugees.

Under the Tax on Postal Articles Ordinance 1971, the Government of India imposed the RRT throughout the country that came into force on November 15, 1971. Although use of the RRT was intended to be on a national scale, there were several situations in which there was an exemption from collection of the tax. The most significant exemptions were for transmission of postcards and literature for the blind, letters from members in active military service, and initially for letters from the State of Jammu and Kashmir (this provision was later modified on July 1, 1972 and the tax made mandatory throughout India).

While drafting of the tax scheme, a clause was added: payment of RRT had to be indicated through the use of an additional, 'altered' five paisa tax stamp, in addition to the usual postal charge for the service. A simple use of a stamp with 5 paisa in additional value of the correct postal fee was not sufficient. Thus effectively, beginning November 15, 1971 for the RRT to produce significant results India needed a steady supply of special stamps, and that too, in millions!

India had operated one of the largest postal networks since the middle ages, and by 1971 it had over 3000 head post offices serving the people and their needs for communication.

To ensure taxation with utmost urgency, the post office took steps that looked into the matter of proper functioning of the new scheme. First, to meet the sudden demand of stamps that this tax would create, the five paisa 'Family Planning' stamp then in circulation was overprinted with the words "Refugee Relief" in English and Hindi at the Security Printing Press in Nasik. Secondly, a separate stamp with a unique design especially meant for collecting tax was planned, but as such measures needed time, provisional measures were taken to get stamps printed in various regions in the country. Stanley Gibbons, the popular stamp catalogue, lists some of these provisional issues emanating from Alwar (in Rajasthan); Bangalore; New Delhi; Goa, Daman, and Diu Union Territory and Jabalpur (Madhya Pradesh). Several unlisted types have now been discovered, which remain to be included in standard reference books.

On December 1, 1971 the new 5 paisa stamp, showing an image of a refugee family fleeing persecution was released. The task of distributing the all-India Nasik overprints or the new RRT stamps to the entire network of post offices was neither a feasible option, nor was it even attempted. And, necessity gave rise to novelty! The postal authorities in a general order allowed all postmasters to prepare, through their own initiatives, handstamps with the words "Refugee Relief" that could be applied on the 'Family Planning' stamp. At some offices, due to short supply of the 'Family Planning' issue, other stamps were overprinted (sometimes combined to make up the 5 paisa). A similar set of issues was made for 'Service' stamps, adhesives that are exclusively used by government office.

A closer examination of the handstamps reveals that there was little attempt to imitate the Nasik prints. Hindi was not used in handstamps in West Bengal and the South, where it is not the commonly spoken. It is a mammoth task to attempt to make even a cursory representation of the various forms of handstamps that were in use. Focusing on the English text alone, one sees variations in cases, fonts, etc. Sorting the multiple variations of Hindi poses a stiffer challenge due to the language barrier. In all reality, variations are plentiful; misspellings observed and sometimes fancy alterations in the form of frames and circles found. Till the last day of taxation, all forms of RRT stamps were accepted and they ran simultaneously. In moments of utter urgency, even the pen came in handy – the postal clerk would just write "RRT" to show the prepayment of tax!

It was a reasonable step to exclude postcards within the framework of the tax to keep some channels open for tax-free correspondence. All other stationery were uprated simply by addition of any RRT tax stamp, but for easier handling of mail, four new distinct stationery types, each showing an additional 5 paisa design, representing the tax were issued. As RRT was obligatory even on mail addressed to foreign destinations, the 85 paisa orange, foreign aerogramme was also uprated with a deep blue RRT die resembling the definitive stamp showing the refugee family.

It was quite natural that the RRT - being the first of its kind in India - will reveal some unprecedented oversights. Since day one of introduction accounting issues had to be dealt with, especially in offices that handled mail in large volumes. As per rule, a separate 5 paisa stamp had to be affixed on articles to show payment of the tax. That meant a lot of stamps and a lot of glue! Separating stamps from their sheets and affixing them on envelopes was a clumsy, time-consuming affair and something simpler had to be introduced - postal clerks used handstamps marked "Refugee Relief Tax Prepaid in Cash" on envelopes; postal stationery were sold at post offices with such markings, which in turn could be used on any future date. Although orders were sent to suppliers of postmarks at Aligarh in Uttar Pradesh for a supply of oval handstamps bearing the inscription "Refugee Relief Tax Prepaid in Cash", to make matters even simpler, general provisions were made for preparing rubber dyes at the local level.

Since the first days of the tax, complaints were lodged as this meant laborious accountancy work at the post offices - the income had to be separately accounted for. Government offices used 'Service' stamps, and these were supplied by state treasuries, which of course had their own supply problems. If an article was posted without the proper prepayment of RRT, the letter was marked "Postage Due" and a penalty, twice the original tax (10 paisa) charged from the recipient. It was quite problematic for institutions that were on the receiving end of mail in large numbers; any letter addressed to such addresses meant that the 'due' was to be collected from them and not the sender, resulting in acute bookkeeping issues. Such grievances were expressed in newspapers during the early days of taxation.

In early 1973, in a letter from the DG, P&T Delhi, to all heads of circles, the RRT was repealed in effect from April 1, 1973. This order embraced all RRT postage and other stamps, so that remaining stocks of RRT adhesives could be exchanged, along with postal stationery, etc., at local offices and treasuries till the end of six months – September 30, 1973.

RRT of India has, in the last four decades, intrigued students of philately. Study of modern postal emissions from the Indian subcontinent is extremely difficult due to lack of proper documentation and open access to archives. Collectors are therefore faced with a situation where only empirical studies can be formed.

1971 saw a humanitarian crisis of unimaginable proportion and this, when tagged with our nationalistic fervour, makes RRT a special subject for the understanding of our past. The RRT of India is probably unique in the philatelic world in the sense that it chronicles the last days of unified Pakistan, the third Indo-Pak War, and a global turning point that led to the emergence of Bangladesh. To any student of Bangladesh philately, RRT remains an interesting collecting avenue and also a testament to the volatile political scenario that helped bring us freedom.

The writer is a sub-editor at The Daily Star and a philatelist.

Illustrations are from the collections of Peter Leevers, Ron Klimley, Uttam Singha, and the author.

References:

"India Post", the Journal of the Indian Study Circle for Philately.

Personal correspondence with Peter Leevers.

"India Refugee Relief Tax 1971-73" exhibit by Ron Klimley

www.genocidebangladesh.org [Last accessed: December 5, 2016]

www.indiabudget.nic.inorg [Last accessed: December 5, 2016]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments