The flavour of change: Edible Oils in Bangladeshi Kitchens

Edible oil is an essential component of the Bangladeshi diet, with consumption steadily increasing as the nation transitions from a lower-income to a higher-income economy, driven by enhanced purchasing power. However, the country's heavy reliance on imports leaves it highly vulnerable to global price fluctuations, which significantly influence local demand and affordability. Consequently, many people struggle to access edible oil at reasonable prices, prompting government intervention—often through reduced import taxes—to stabilise the cost of this indispensable commodity.

Food experts generally view the growing consumption of edible oil as a positive development, noting its crucial role in addressing nutritional deficiencies, particularly among lower-income and impoverished populations. For many, edible oil is vital for meeting dietary requirements and enhancing overall nutrition.

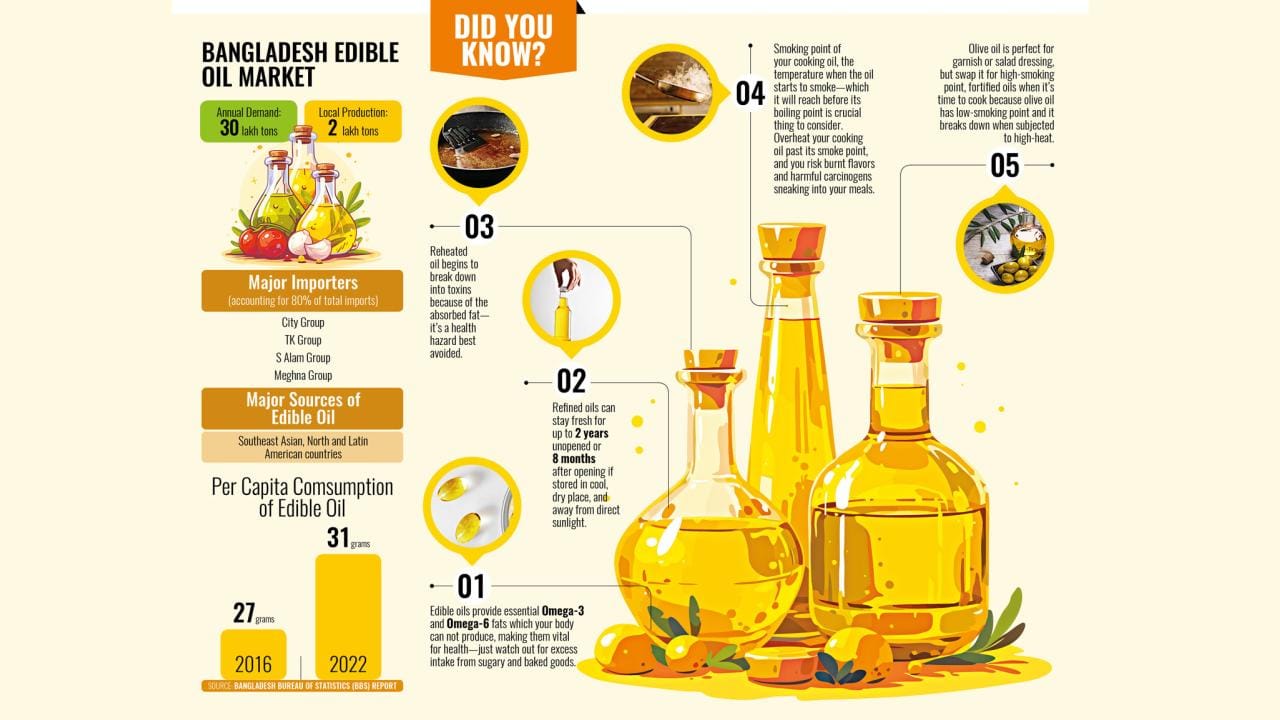

According to the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) Household Income and Expenditure Survey, per capita consumption of edible oil increased from 27 grams per day in 2016 to 31 grams per day in 2022, indicating a steady upward trend in food consumption.

"The edible oil market consists of both branded and unbranded segments. While the unbranded market remains dominant, particularly in rural areas, branded oils are gradually gaining popularity due to their quality assurance. The demand for fortified edible oils, such as those enriched with Vitamins A and D, has risen significantly, driven by government regulations and health awareness campaigns," notes Md. Abdulla Al Mamun Fahim, Deputy Brand Manager at City Group.

Unpackaged palm and soybean oils continue to dominate the market, largely due to their more affordable prices compared to bottled alternatives. However, food experts warn that these unpackaged oils often fail to meet essential health and safety standards, whereas bottled oils offer better quality assurance.

In a recent study, Dr. Nazma Shaheen, Professor and former Director of the Institute of Nutrition and Food Science at Dhaka University, found that palm oil is often mixed with soybean oil and sold as pure soybean oil in the unpackaged market. This deceptive practice leads to financial losses for consumers, though it becomes less common during the winter months, when palm oil solidifies at lower temperatures.

Dr. Shaheen also highlights the significant difference between unpackaged and bottled soybean oils. While bottled soybean oil is authentic and meets universal fortification standards, including the mandatory addition of Vitamin A, unpackaged oils face major issues. Exposure to light and heat in the open market causes degradation of Vitamin A, increases peroxide values, and accelerates oxidation, all of which reduce the shelf life of unpackaged oils. Despite its larger market share, unpackaged oil is less healthy.

Approximately two decades ago, mustard oil was the dominant choice among consumers. However, the landscape shifted significantly as soybean oil gained popularity. According to industry insiders, the local edible oil market is now predominantly reliant on two major imports—palm oil and soybean oil—which together account for approximately 85–90% of total demand.

Recently, mustard oil has been experiencing a resurgence in demand, with several leading companies now offering branded bottled mustard oil alongside their soybean oil products. Additionally, other types of edible oils, such as sunflower, canola, and olive oil, are gradually gaining traction. However, their market share remains minimal, as they are mainly preferred by health-conscious, higher middle-class consumers.

Bangladesh's annual edible oil requirement currently stands at approximately 30 lakh tonnes. Soybean, mustard, groundnut, sunflower, and sesame seeds are cultivated locally for edible oil production, but domestic production meets only a modest demand of 2 lakh tonnes.

Edible oil imports are predominantly sourced from Southeast Asian, North American, and Latin American countries. With both import and local distribution concentrated among a few companies, the process requires substantial financial resources, often necessitating large bank loans.

Over the years, the number of refiners in Bangladesh has declined by a third, as many were unable to sustain their operations. Currently, only 11 companies remain active in the edible oil market. This decline is primarily attributed to the price instability in the global commodities market, on which Bangladesh heavily relies to meet its edible oil requirements. Among the remaining refiners, TK Group, City Group, S Alam Group, and Meghna Group dominate the imported edible oil market. In 2023, nearly 25.7 lakh tonnes of soybean and palm oil were imported, with these four companies accounting for 80% of the total imports.

In October, the government significantly reduced import taxes on edible oil. The National Board of Revenue (NBR) lowered the VAT on soybean and palm oil imports from 15% to 10%. Furthermore, VAT at both the production and trading stages of this highly import-dependent commodity was fully waived. According to the NBR, these tax reductions will remain in effect until 15 December this year.

The decision followed a recommendation from the Bangladesh Trade and Tariff Commission (BTTC) to reduce indirect taxes as a measure to stabilise edible oil prices, given that 90 percent of the country's demand is met through imports.

A food expert emphasises that reducing import duties on edible oil is merely a short-term solution to make prices more affordable for the public.

Professor Shafiun Nahin Shimul from the Institute of Health Economics at Dhaka University emphasises that the government should engage regularly with importers, carefully monitoring their pricing strategies. This should be done by comparing local prices with international market rates, as global price data is readily accessible. Such scrutiny will help identify any discrepancies in pricing.

One issue often raised by importers is shipment delays of two to three months, which they claim justify price increases. However, these claims must be carefully scrutinised to ensure their legitimacy. If any fraudulent activities are discovered, appropriate corrective actions should be taken to protect consumers.

At the same time, Professor Shimul warns that the government must be cautious not to exert excessive pressure on importers. Overbearing tactics could discourage them and disrupt the market's supply chain, leading to unintended consequences.

Looking towards the long-term, he suggests that opening the market to more importers would help foster healthy competition. This could contribute to price stability, as seen in the past when the importation of sufficient quantities of eggs led to a noticeable drop in prices. Similarly, maintaining a steady and consistent supply of edible oil would help mitigate the frequent fluctuations in its price.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments