My three martyred teachers

The month of December is a month of joy and celebration all over the world, and in Bangladesh as well. But to me, it brings back the horrid memory of the killing of intellectuals on December 14-15, 1971, when the Pakistani army realised that they had no chance of keeping East Pakistan under their control and to stop the emergence of an independent country which was already named Bangladesh. They wanted to rob Bangladesh of learned people and cripple us forever. The military-junta found good allies in the Jamaat-e-Islami and their creation, "Al-Badr" and "Al-Shams."

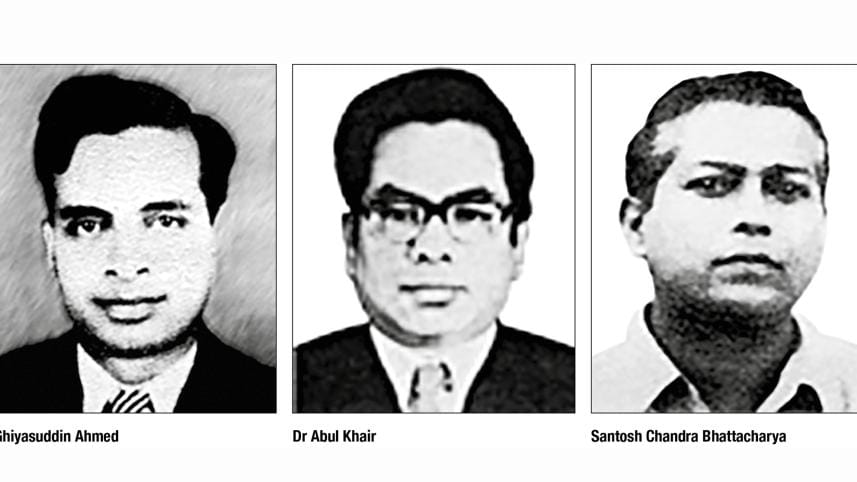

Three of my teachers, Santosh Chandra Bhattacharya, Dr Abul Khair, and Ghiyasuddin Ahmed, of the History Department of Dhaka University, were among the intellectuals who embraced martyrdom.

I had a close relationship with Ghiyas bhai, who was my teacher when I was a student of third year BA Honours class. After his Masters in 1957, and a short stint as a teacher in Notre Dame College, he joined Dhaka University as a lecturer in 1959. His students were mesmerised by his handsome figure, strong personality, and commanding voice.

In 1960 or 1961, a group of MA students went to India on a study tour and three teachers accompanied the party – Professor Mafizullah Kabir, Ghiyas sir, and me.

When we reached our hotel in Allahabad, we realised that one of the students had contracted small-pox. It was decided that he would return to Calcutta where he had a relative. But he could not be sent back alone; if someone found out in the train that a certain passenger had small-pox, he would be off-loaded in the nearest town and sent to the hospital. The student would have to cover himself with a blanket and sleep on the upper berth. Then came the question of who would accompany the sick student. Before anyone else could volunteer, Ghiyas bhai insisted it be him.

The next night, Ghiyas bhai and the sick student left for Calcutta. I narrate this incident just to give the readers an idea of how he was always eager to help others at the cost of his own interest.

After our return to Dhaka within a few days, Ghiyas bhai showed signs of having contracted the disease. He confined himself in his DU teacher's hostel near the present Badrunnesa College. I used to visit him every day after my classes and I used to hear him say, "Please don't come near me; the disease is highly contagious."

Ghiyas bhai was not a political activist as such. His involvement in the Liberation War was rather indirect. He had good relations with all his students. As a house tutor at Mohsin Hall, he had contact with many students who were involved in the Liberation War. He used to support them with money, medicine, and even arranged medical help for injured students through his younger brother Dr Rashiduddin Ahmed, who was a neurosurgeon.

That was the crime for which Ghiyas bhai was killed. His straight forward nature, dedication, and love for the students made him a remarkable teacher. Even when he was picked up by the Al-Badr/Al-Shams people, Ghiyas bhai was in the pump house of the hall. As a house tutor, he felt duty bound to attend the repairing of the water pump. His strong sense of duty did not allow him to leave his house tutor's quarter, when many were leaving their homes sensing imminent action by the Pakistani occupation forces.

Mr Santosh Chandra Bhattacharya, our SCB, was a true Brahmin in look and practice. He always had a smile on his face and looked very graceful with grey-white hair covering his head. No student can forget his habit of standing in the corridor and enjoying the last puff of his cigarette and enter the classroom right on time.

Soon after Operation Searchlight, people from Dhaka started leaving the city towards the villages thinking that the Pakistani occupation army would find it difficult to move towards the villages. Possibly on March 27, 1971, my wife and I, with our seven-day-old daughter in her lap, our three-year-old son on my shoulder, crossed the Buriganga and started walking southward towards my ancestral village home, about 25 miles away.

I heard from Ghiyas bhai that he and one of our students, Selim, had succeeded in convincing SCB to leave his university quarter and spend the first night in Selim's house in the old part of the then Dhaka. SCB was always protesting against this move saying, "Who will kill me and why? I have no connection with politics. Moreover, if I am killed, I would feel myself fortunate that I died in my motherland; I was born here and I died here. During the 1947 partition, I did not leave my motherland though there was a huge migration of non-Muslims to India."

Selim arranged for him to be moved to a part of the country from where one could come to Dhaka only by motorised river crafts. SCB with his family lived in the village till June, 1971.

The Pakistani administration announced an order in late May asking all employees of government and autonomous bodies to return to Dhaka and join their jobs. SCB's loyalty to Dhaka University goaded him to take the motor-launch and reach Dhaka early on June 1, 1971, and he surprised everyone in the department with his presence there. His son and daughter managed to cross the border and escape the brutality of the Pakistani army. But SCB and his wife refused to leave, though Ghiyas bhai and some freedom fighter students had arranged their passage through Agartala. Evan a burqa was purchased for Mrs SCB. Even today, we admire SCB's love for his motherland and the valiant way he faced his departure from this world.

When I entered Dhaka University in 1956 as a student, Mr MA Khair taught us in our first year. He was a soft-spoken gentleman, who used to believe in an independent Bangladesh. In 1952, he was an activist in the Language Movement and participated in the precession that broke Section 144, which was imposed on February 21. In an encounter with the police, Mr Khair was injured. He tried to inspire students by narrating the history of America's independence. After his return in 1962 with a Ph.D. from Barkley, University of California, he became very straight forward and used to speak his mind during the movements of 1966 and 1969. He wrote articles on the concept of the welfare state, human rights, and equality of humankind, which were absent in the state of Pakistan. He was very friendly with Mr Tajuddin Ahmed of the Awami League, who used to visit Khair sir's residence often.

Dr Khair spent quite a few days in the custody of the Pakistani army, where other DU teachers including Professor Rafiqul Islam from the Bangla Department were being held. About their confinement, Professor Islam wrote that Dr Khair used to keep up their morale by saying, "It is certain that one day the country will be independent. Maybe we will not see that." The DU teachers spent 22 days in, what Dr Khair used to say, was a "concentration camp". He had a very strong mind and was an intellectual who was a firm supporter of the liberation of Bangladesh.

I would finish my homage to my three martyred teachers by saying that East Pakistan could be liberated from the Pakistani occupation forces resulting in the emergence of an independent Bangladesh because of the sacrifice of such dedicated persons, who embraced death gracefully and never surrendered to the brutes. I would only hope that the blood of the martyrs gets due respect from the present generation, and the wish of the intellectuals of a welfare state with equality of humankind is fulfilled not only in words, but also in action.

Dr Abdul Momin Chowdhury is retired professor of History, University of Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments