What is the future of the Ganges Waters Treaty?

As the Ganga/Ganges Waters Treaty (GWT) is going to complete 30 years of its term in December 2026, the question is: what will happen after that? During the last days of what many political analysts from the two sides termed the "golden chapter" or "golden era" of their ties under Sheikh Hasina, India and Bangladesh agreed to renew the GWT. Hasina's long "authoritarian" rule, though it improved the country's economy, "damaged democracy" in Bangladesh. She was thrown out of power following strong protests led by the students, in which around 1,500 Bangladeshi citizens were killed.

After Hasina left the country, an interim government under Professor Muhammad Yunus took charge of the interim government. The Yunus-led government does not share cordial ties with New Delhi for political reasons. However, officials from the two countries have occasionally interacted on common issues, including water sharing. In February 2025, during a meeting with India's External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar on the sidelines of the eighth Indian Ocean Conference in Muscat, Oman, Bangladesh's Foreign Affairs Advisor Touhid Hossain "sought to initiate discussions for the renewal of the Ganges Water Treaty signed in 1996". In March 2025, the 86th meeting of the India-Bangladesh Joint River Commission (JRC) and Technical Committee on Ganges water sharing was held in Kolkata in West Bengal. This meeting was a part of the structured engagement under the GWT and is held three times in a year. In September 2025, the JRC met again in New Delhi.

Nonetheless, the GWT's political future hinges on the nature of bilateral ties between India and Bangladesh, and assent from the West Bengal government. At the physical level, the widening supply–demand gap in water flow in the Ganga River Basin region will highly influence the provisions in any draft that the two countries prepare to renew the treaty or negotiate the provisions on water sharing.

A brief political history of the GWT

After Bangladesh was liberated in 1971, India and Bangladesh signed a "Treaty of Peace and Friendship" in March 1972. Under Article 6 of the Treaty, the two countries agreed "to make joint studies and take joint action in the fields of flood control, river basin development and the development of hydro-electric power and irrigation". The initial bonhomie between India and Bangladesh did not last long, and relations deteriorated after the assassination of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman on August 15, 1975.

The military government under General Ziaur Rahman was not considered "friendly" to India. Bangladesh raised the Farakka and the Ganga water issues at the Colombo Summit of the Non-Aligned Movement in 1976, followed by the Islamic Foreign Ministers' Conference in Istanbul in 1976, and finally at the United Nations General Assembly in 1976. Following the raising of the matter in the UNGA, the non-Congress Janata Party government in India signed an agreement with Bangladesh to share the Ganga water in November 1977. The Ganga water sharing agreement was in force for five years. After its termination in 1982, ad hoc agreements in the form of Memoranda of Understanding were made on the Ganga waters. In December 1988, Bangladesh proposed a permanent arrangement on the Ganga to which India did not agree. At that time, another military head, General H.M. Ershad, was in power in Bangladesh. In 1993, the then Bangladeshi Prime Minister Khaleda Zia (1991–96 and 2001–06) raised the water issues in the UNGA, accusing India of not agreeing to water sharing. New Delhi countered Dhaka by accusing it of doing politics on water matters.

The suspension of the IWT casts a shadow on the GWT because of the nature of the present ties between India and Bangladesh. The Indian media has quoted a senior officer at its Ministry of External Affairs saying, "Before Pahalgam, we were inclined to extend the treaty for another 30 years, but the situation changed drastically afterwards."

Three years later, in 1996, with the Sheikh Hasina-led government in Dhaka, India agreed to the Ganga/Ganges Waters Treaty. Besides having a friendly Hasina in power, the GWT was possible because of the "Gujral Doctrine" introduced by I.K. Gujral, the then Indian Foreign Minister, in a coalition government under H.D. Deve Gowda. The Gujral Doctrine called for close friendly ties with neighbours and underscored that "with its neighbours like Bangladesh, Bhutan, Maldives, Nepal and Sri Lanka, India does not ask for reciprocity, but gives and accommodates what it can in good faith and trust". Lastly, the then Chief Minister of West Bengal, Jyoti Basu, supported the GWT, hoping that the treaty would facilitate better ties in other areas of mutual interest as well. The GWT was questioned and opposed in the respective countries by the opposition political parties.

As water sharing brings disputes, Article VII of the GWT has a provision to settle the matters first at the Joint Committee (JC) level, which is responsible for implementing the arrangements in the treaty. If the JC fails, the matter is referred to the Indo-Bangladesh JRC. If the JRC also fails, the differences and disputes are referred to the two Governments, who are required to meet soon to resolve them. Notwithstanding criticisms, and the arguments and counterarguments put forth by analysts, the GWT has worked for about 29 years. Now, with a change in India-Bangladesh ties and the accelerating impact of climate change, there are physical and political hurdles to the renewal of the GWT.

In the post-Hasina times, although India's Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri went to Dhaka in December 2024, S. Jaishankar met Touhid Hossain, and Bangladesh's National Security Advisor Khalilur Rahman was in Delhi to attend the Colombo Security Conclave in November 2025, the two top leaders from the respective countries are yet to meet in each other's capital.

Hurdles in the renewal of the GWT or negotiating a new water sharing arrangement

Renewal of the GWT is relatively easier than negotiating a new water sharing arrangement or fully or partially renegotiating the existing treaty. Negotiation or renegotiation needs a conducive political environment where representatives from the two countries can negotiate. Second, the objective of negotiation depends on the composition of the negotiating team. A diplomat leading a negotiating team looks for maximum political advantage to his or her country, while a technocrat may like to focus more on the technical aspects of the matter under negotiation. Finally, negotiation/renegotiation and its result need support from major political actors, institutions, and a big section of the public from the two countries.

In the post-Hasina times, although India's Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri went to Dhaka in December 2024, S. Jaishankar met Touhid Hossain, and Bangladesh's National Security Advisor Khalilur Rahman was in Delhi to attend the Colombo Security Conclave in November 2025, the two top leaders from the respective countries are yet to meet in each other's capital. However, the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi met Yunus on the sidelines of the BIMSTEC (Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation) Summit in April 2025. On the regional geopolitical front, India is concerned about Dhaka's growing closeness with Beijing and Islamabad. Such a state of bilateral relationship affects their water sharing matter.

According to the Ecological Threat Report 2025, since 2015, conflicts on shared waters have increased in comparison to cooperation. The report recorded that the most conflicts were in the Middle East, followed by South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. India's unilateral decision to hold the 65-year-old Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) with Pakistan in abeyance after 26 tourists were killed by terrorists in Pahalgam in Jammu & Kashmir in April 2025 has added to the existing tensions between the South Asian nuclear rivals. The suspension of the IWT casts a shadow on the GWT because of the nature of the present ties between India and Bangladesh. The Indian media has quoted a senior officer at its Ministry of External Affairs saying, "Before Pahalgam, we were inclined to extend the treaty for another 30 years, but the situation changed drastically afterwards."

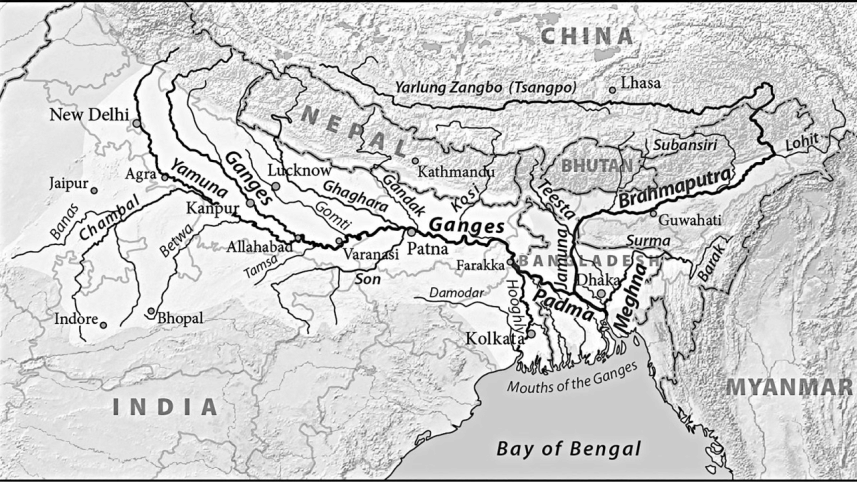

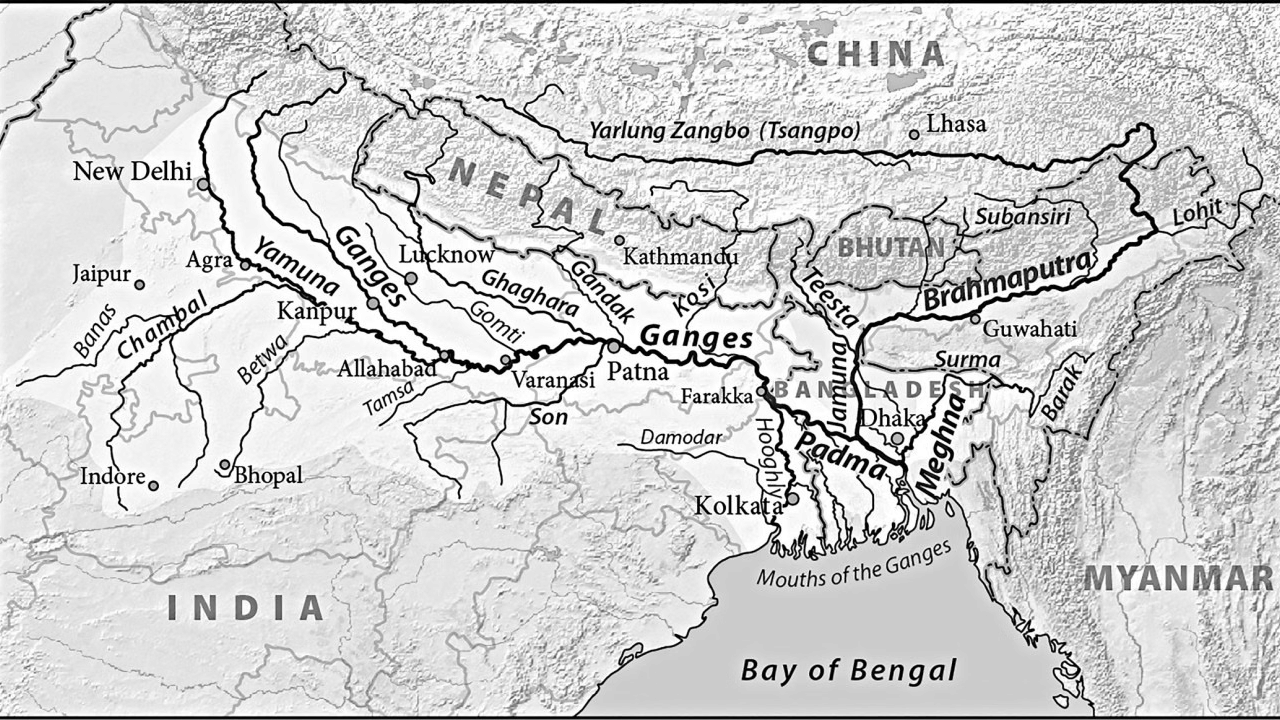

Physically, the Ganga River forms around 129 kilometres of the boundary between India and Bangladesh and flows for about 113 km in Bangladesh before falling into the Bay of Bengal. In a study, Dipesh Singh Chuphal et al. find that the Ganga River Basin, which supports the water needs of more than 600 million people, is witnessing a "severe and unprecedented drying trend". The study observes that between 1991 and 2020, there have been only two extreme wet years for the basin, while the basin saw 15 droughts during the same period. Then the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development report, titled Water, Ice, Society, and Ecosystems in the Hindu Kush Himalaya (HKH), found how the melting glacier affects the flow in the HKH rivers. In short, decline in water availability in the Ganges basin will affect the negotiation and smooth working of any water-related treaty or arrangement between India and Bangladesh.

In the GWT, the indicative schedule provided in Annexure-II mentions that the share of water to each side at Farakka between January 01 and May 31 every year is based on 40-year (1949–1988) old data on 10-day period average availability of water at the barrage. Due to an increase in population and growth in water demand, it is unlikely that India and Bangladesh will agree on the old water data for a new arrangement on the sharing of the Ganges' waters. Media reports say that Bangladesh, in the JRC's meeting in New Delhi, pressed for guaranteed release of an average of 40,000 cusecs of water during the lean months, between February and May, instead of 35,000 cusecs under the 1996 treaty.

Three years later, in 1996, with the Sheikh Hasina-led government in Dhaka, India agreed to the Ganga/Ganges Waters Treaty. Besides having a friendly Hasina in power, the GWT was possible because of the "Gujral Doctrine" introduced by I.K. Gujral, the then Indian Foreign Minister, in a coalition government under H.D. Deve Gowda. The Gujral Doctrine called for close friendly ties with neighbours and underscored that "with its neighbours like Bangladesh, Bhutan, Maldives, Nepal and Sri Lanka, India does not ask for reciprocity, but gives and accommodates what it can in good faith and trust". Lastly, the then Chief Minister of West Bengal, Jyoti Basu, supported the GWT, hoping that the treaty would facilitate better ties in other areas of mutual interest as well. The GWT was questioned and opposed in the respective countries by the opposition political parties.

On the duration of the treaty, the Indian media has reported that New Delhi has communicated to Dhaka about its increased water needs, and the new treaty may be shorter, lasting 10–15 years. Conversely, during the JRC meeting in New Delhi, Bangladesh conveyed to India that it desires a long-term treaty on Ganges water sharing and a more predictable water flow. Bangladesh has proposed a new "institutional mechanism" to oversee water-sharing from 14 rivers, including the Muhuri, Khowai, Gomati, Dharal, and Doodhkumar. However, India suggested strengthening the existing JRC framework.

Politically, unlike in 1996, when Jyoti Basu was supportive of the GWT, the present Chief Minister of West Bengal, Mamata Banerjee, is not in favour of renewing the treaty. Her objection is genuine due to the increasing demand and the decline in water availability in West Bengal. Earlier, her stand on the interim deal between India and Bangladesh on the Teesta waters kept the pact inconclusive. Hence, convincing Mamata Banerjee is a big challenge for the Indian political leadership.

Conclusion

The fate of the GWT is tied to the course of India–Bangladesh relations, which will become clearer after Bangladesh's national elections in early 2026. The main political parties from Bangladesh, such as the Bangladesh Nationalist Party and Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami, have expressed a hope of having neighbourly ties with India. However, the broader relationship will largely depend on the willingness of both countries to engage constructively, and listen, understand, and try to address each other's genuine concerns.

On June 20, Bangladesh became the first country in South Asia and the 56th globally to officially accede to the UN Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes (UN Water Convention). By acceding to the UN Convention, it is argued that Bangladesh can use provisions to protect its lower riparian water interests by proving that its rights are supported by the international charter and by building public opinion on the international forum. Articles 5, 6, 7, 20, and 33 of the Convention on the Law of the Non-navigational Uses of International Watercourses 1997 have important provisions on watercourses and dispute settlement. India is not a party to the Water Convention, and after signing the IWT, it has strictly kept transboundary waters a bilateral issue. In such a situation, as in the past, Bangladesh may raise the water issue on international forums. India has to stay prepared with its response.

Even if India and Bangladesh renew the GWT, its successful implementation hugely depends on support from the West Bengal government. A prior assent of the West Bengal government may avoid a Teesta River deal–like situation on the Ganga/Ganges water.

Amit Ranjan is a Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies, National University of Singapore.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments