Restoring caretaker system with more safeguards

Very few topics in Bangladesh's political discourse have sparked as much debate or endured as long as the caretaker government system. To many, it represents not just a procedural framework but also a reliable means of conducting free and fair elections.

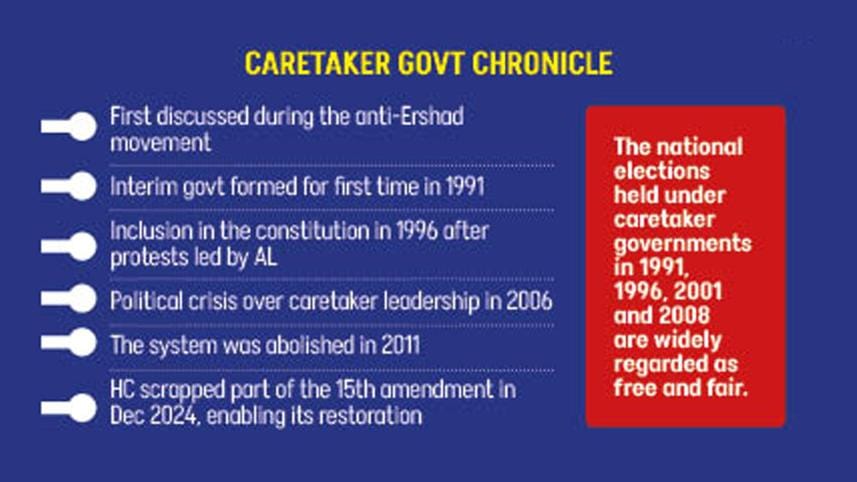

Introduced in 1991 through a rare political consensus, the caretaker system was widely accepted as a safeguard to ensure neutral elections, free from the influence of ruling parties. It was incorporated into the constitution in 1996.

Its unilateral abolition by the Awami League government in 2011 triggered a decade-long bitter dispute over an acceptable mechanism for holding credible elections.

The issue has emerged again with renewed urgency, as the July charter calls for the restoration of the system.

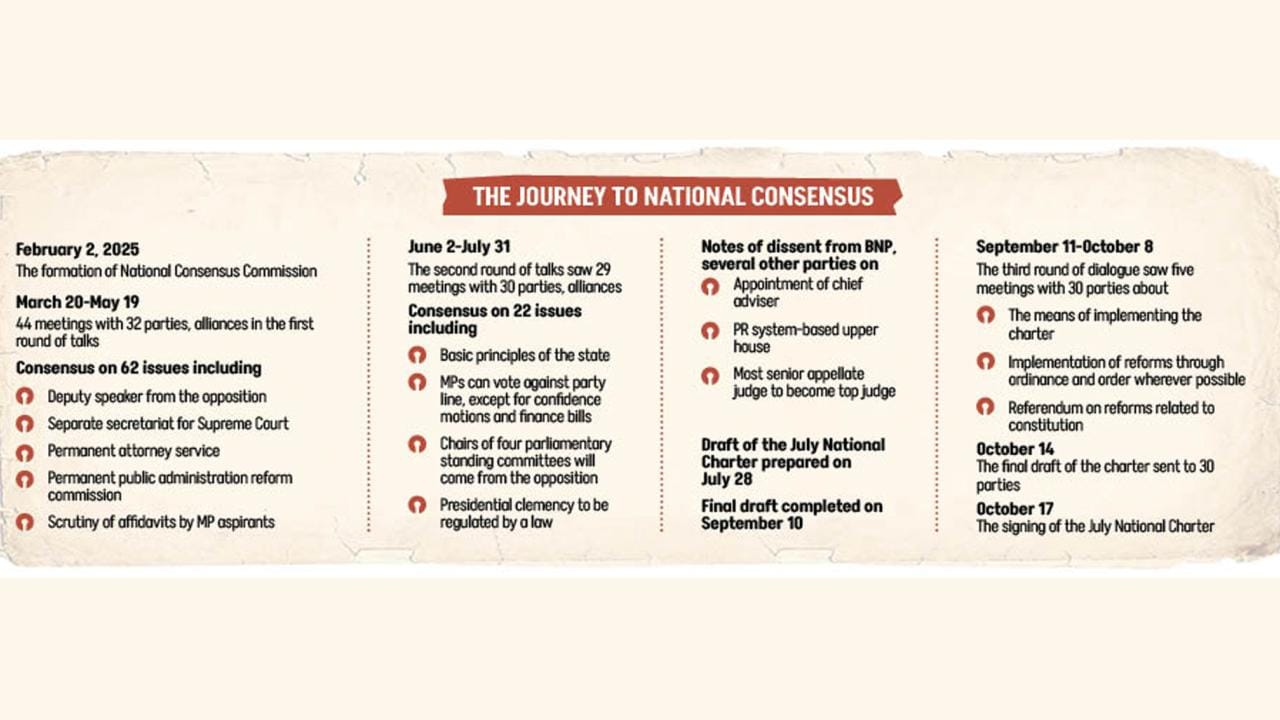

In the first round of discussions, almost all political parties backed the system's revival.

The parties reached a consensus that any amendment to the constitutional provisions concerning the caretaker government system (articles 58B, 58C, 58D, and 58E) would require a referendum.

The July Charter outlines a detailed framework for appointing a chief adviser, aiming to institutionalise electoral neutrality and rebuild public confidence in the ballot box.

Noting that polls under a political government were not free or fair, Badiul Alam Majumdar, a member of the National Consensus Commission, said, "They have been controlled, and that is a major reason behind the rise of authoritarianism… That is why a non-partisan interim government is crucial during elections."

"It was included in the constitution through a collective decision, but was later removed in a completely unilateral manner," he said.

Sk Tawfique M Haque, professor of political science and sociology at North South University, said that in Bangladesh, a truly neutral election is impossible without a non-partisan caretaker government. One might ask how India manages without it, as do neighbouring countries such as Nepal and Sri Lanka.

"But our reality is different… We have not yet been able to build strong, impartial institutions. Our Election Commission lacks neutrality, the judiciary is not fully independent, and the administration is not politically neutral. That is why we still need a caretaker system."

CARETAKER GOVT FORMATION

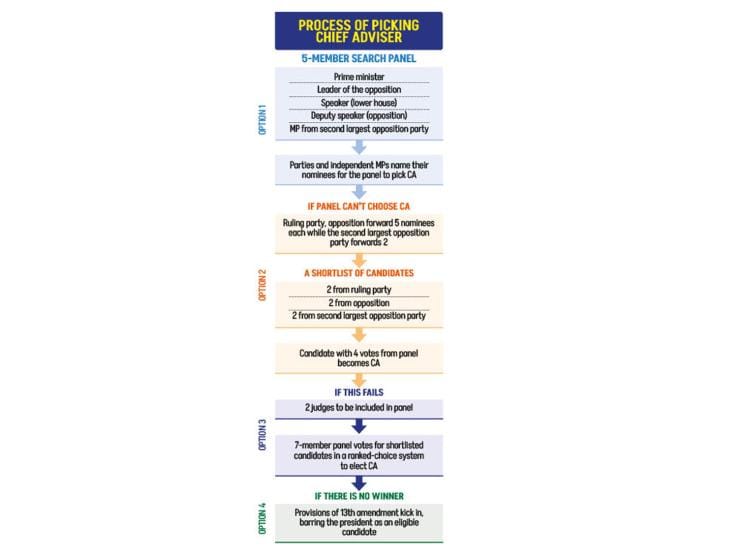

According to the July Charter, a five-member panel comprising the prime minister, the leader of the opposition, the speaker (the lower House) and the deputy speaker (from the opposition), and a representative of the second-largest opposition party will be formed to pick chief adviser from a pool of nominees.

The panel will invite parties with representation in parliament as well as those registered with the EC, and independent MPs to propose names of individuals qualified to serve as chief adviser. Each party and independent MP may propose only one name.

The committee will then deliberate on the proposed individuals as well as those it identifies through its own enquiries. From among eligible citizens, one individual will be selected as chief adviser of the caretaker government and appointed by the president.

If this first option fails, then both the ruling party and the opposition will put forward five nominees each. The second largest opposition will put forward two nominees.

The main opposition will select one from the ruling party's list, and vice versa. They will also pick one nominee from the second-largest party's list. At this point, four out of five panel votes will suffice to select a chief adviser from the short list.

But failing this second option, two judges -- one from the Appellate Division and one from the High Court Division -- will join the panel. This seven-member panel will vote for the shortlisted nominees in a ranked-choice method to select one as chief adviser.

This method requires the panel members to score candidates according to preference -- one for the first choice, two for the second choice, and so on.

Failure to select one nominee at this point will invoke provisions of the 13th amendment to the constitution, with the condition that the president be kept out of consideration.

Several parties, including the BNP, submitted notes of dissent against the inclusion of judges and the use of ranked-choice voting. They suggest that if the second option fails, parliament should vote to pick chief adviser from the short list.

Following the appointment, the chief adviser will be required to consult the panel and select up to 15 advisers.

The chief adviser must be under the age of 75, as stipulated by the conditions. The term of the election-time caretaker government will be 90 days except in cases of "act of god" when it may continue for an additional 30 days.

POLITICAL WILL NEEDED

About the process of the caretaker government formation, Tawfique pointed out that political parties often hold divergent views, which inevitably lead to controversy.

"It's unfortunate that we, as a nation, struggle to reach consensus on any issue. A few years from now, when a new name will be proposed for the chief adviser -- regardless of who it is -- some parties will likely object and spark controversy. What will we do then?

"The possibility of a stalemate over a caretaker government cannot be ruled out."

Badiul also warned that a stalemate could arise in the absence of genuine political will.

He hoped that all parties would adopt a realistic approach, keeping in mind the future of democracy and its broader implications.

The caretaker government system was introduced after HM Ershad was forced to resign in 1990. Later, it became a contentious issue, leading to repeated political crises. The BNP adopted the system after prolonged protests led by the AL in 1996.

Another crisis emerged in 2006 amid disputes over who would head the caretaker government. The crisis deepened, leading to a two-year state of emergency in 2007-08 when a military-backed caretaker government was at the helm.

In 2011, two years after assuming power, the AL-led government abolished the system through the 15th amendment. It repeatedly ignored the opposition's demand for a caretaker government system ahead of the national elections in 2014, 2018, and 2024.

In December last year, the High Court struck down part of the 15th amendment to the constitution that had abolished the system.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments