Facing up to an uncertain future

7 September 2018, 18:10 PM

Child Alert - UNICEF 2018

Nutrition / A POTENTIAL KILLER HIDING IN PLAIN SIGHT

7 September 2018, 18:00 PM

Child Alert - UNICEF 2018

Caring for premature Bangladeshi and Rohingya babies alike

7 September 2018, 18:00 PM

Child Alert - UNICEF 2018

Health / Extending the benefits of primary health care Across both communities

7 September 2018, 18:00 PM

Child Alert - UNICEF 2018

Water, Sanitation & Hygiene / Providing safe water to refugees and local communities alike

7 September 2018, 18:00 PM

Child Alert - UNICEF 2018

The de-sludgers of Chakmapur

7 September 2018, 18:00 PM

Child Alert - UNICEF 2018

How one Rohingya girl avoided missing out on school

7 September 2018, 18:00 PM

Child Alert - UNICEF 2018

Education / Avoiding a “lost generation” of rohingya children

7 September 2018, 18:00 PM

Child Alert - UNICEF 2018

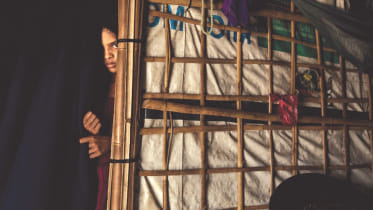

Cloistered within their own homes

7 September 2018, 18:00 PM

Child Alert - UNICEF 2018

The girl who vanished without a trace

7 September 2018, 18:00 PM

Child Alert - UNICEF 2018

Facing up to an uncertain future

Jomtoli refugee camp occupies one of the higher vantage points from which the hills of Myanmar's Rakhine State are clearly visible. Early evening finds groups of Rohingya gathering at this spot, mobile phones in hand, hoping for a signal strong enough to gather news from relatives still on the other side of the border.

7 September 2018, 18:10 PM

A POTENTIAL KILLER HIDING IN PLAIN SIGHT

Harder to spot are the babies and children who are not receiving the essential nutrients they need to grow and thrive, and who are therefore at risk of long-term consequences to their health, perhaps including death.

7 September 2018, 18:00 PM

Caring for premature Bangladeshi and Rohingya babies alike

What the labels don't record is that the twins' mother is a Rohingya, a refugee from among the hundreds of thousands who fled into Bangladesh in the last months of 2017.

7 September 2018, 18:00 PM

Extending the benefits of primary health care Across both communities

Health post, Camp 4, Kutupalong camp: There's an unmistakable hint of pride in Dr Kazi Islam's manner as he shows visitors around the bustling primary health care centre where he works as medical officer in charge. At first sight, the location – next to a busy unpaved road through Kutupalong's Camp 4 – is unremarkable.

7 September 2018, 18:00 PM

Providing safe water to refugees and local communities alike

Unchiprang camp: For nine months of the year, the Boro Chara (literally “big mountain stream”) gushes noisily from its source in the wooded hills of southern Cox's Bazar. Since last October, it has played an indispensable role in meeting the needs of Unchiprang refugee camp, where some 22,000 people now live.

7 September 2018, 18:00 PM

The de-sludgers of Chakmapur

Chakmapur camp: “It's a tough job, but because of us, people no longer have to run into the jungle to go to the toilet,” says 35-year-old Hamid Hasina. He and his Rohingya refugee colleagues are taking a break from an unpleasant but critical job – emptying dozens of toilets in Chakmapur camp.

7 September 2018, 18:00 PM

How one Rohingya girl avoided missing out on school

When Rajima, a 10-year-old Rohingya refugee, arrived in Bangladesh in August 2017 she was traumatised, exhausted and frightened. She and her family had recently seen soldiers raze most of their village in Myanmar to the ground.

7 September 2018, 18:00 PM

Avoiding a “lost generation” of rohingya children

Chakmarkul camp, Cox's Bazar: The stump where 13-year-old Mohamed Faisal's left arm once was will forever be a reminder of his terrifying escape from Myanmar – an experience that nearly cost him his life. As he and others from his village ran through a forest near the border, he was struck by a bullet which shattered his arm and left it hanging by a thread.

7 September 2018, 18:00 PM

Cloistered within their own homes

Balukhali camp: For adolescent Rohingya girls, the onset of their first period brings radical change to their lives. They are no longer allowed to move freely, and are expected to remain largely cloistered within their homes until they are married.

7 September 2018, 18:00 PM

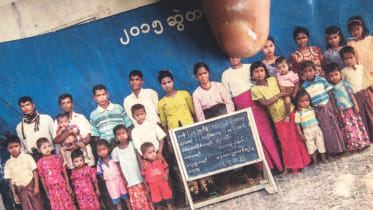

The girl who vanished without a trace

According to Nur Mohamed, a Rohingya refugee living in Hakimpara camp, the girl pictured in the front row is his niece, Rupchanda Begum, then 10 years old.

7 September 2018, 18:00 PM

Disabled boy gets a helping hand

Balukhali camp: Few would dispute that life has treated eight-year old Mohammed Junaid harshly. Born with deformities in both legs, his mother died of a sudden illness in their native Myanmar. His father was shot and killed when the family joined the mass exodus of Rohingya refugees to Bangladesh last year.

7 September 2018, 18:00 PM

A dangerous place for a child

Balukhali camp: One year after the newly-arrived refugees began clearing scrubland and setting up primitive plastic and bamboo shelters, the camps appear more settled and organized. New roads and other infrastructure have been installed. Paths roughly paved with red brick snake through bustling markets, while steep stairways of bamboo and sandbags make crossing the hills on which the camps are mostly built somewhat less hazardous. Street lamps powered by solar panels are increasingly common.

7 September 2018, 18:00 PM

The Team

Child Alert is a briefing series that presents the core challenges for children in crisis locations. Rohingya children are among an estimated 28 million children worldwide who have been uprooted from their homes due to conflict, poverty and extreme weather.

7 September 2018, 18:00 PM

Facing up to the monsoon and an uncertain future

Hakimpara camp: Outside the simple bamboo-and-plastic shelter that 60 year-old Dulu, her husband Salamat and their family call home, there is nothing more than a narrow ledge, less than a metre wide. After that, the ground drops away precipitously into a gully some 50 metres below where shelters belonging to other families have been erected.

7 September 2018, 18:00 PM

A call to action for all Rohingya Children

Despite the immense humanitarian effort led by the Government of Bangladesh over the past year, the lives and futures of more than 380,000 Rohingya children and their families who fled across the Myanmar border in late 2017 remain in peril. The same is true for around 360,000 children - most of them Rohingya - who are in need of humanitarian assistance in Myanmar's Rakhine State.

7 September 2018, 18:00 PM

LONG-TERM SOLUTIONS REMAIN ELUSIVE

Although the visible scars may be slowly fading, the invisible ones are not. The trauma of what happened a year ago is still felt by all communities. Economic activity is down and Muslims continue to face travel and other restrictions, severely limiting their access to services and livelihoods.

7 September 2018, 18:00 PM

Lifesaving Messages Challenge The Camp Rumour Mill

Balukhali camp: In the narrow paths and alleyways that thread past the homes of nearly one million Rohingya refugees, there's nothing that spreads quite as quickly as rumours.

7 September 2018, 18:00 PM