Bangladesh's ailing tax system

The tax system in Bangladesh is not very different from that of most other developing countries. A significant share of revenue is collected at the border, while domestic taxes are primarily from the VAT and income taxes. Overall performance has lagged behind public policy objectives.

The tax system is characterised by an inadequate policy framework, slow pace of administrative modernisation, a high degree of fragmentation, and weak enforcement mechanisms. While a range of incremental reforms have been introduced in various episodes, they have brought only marginal changes to the system.

The most basic challenge has been the inadequacies of the overall policy framework, characterised by exemptions, incentives, and special regimes. These range from the existence of simplified VAT regimes to significant scope for tax officials and political elites to grant discretionary benefits. This not only undermines revenue collection but also complicates administration.

Room for discretion within the law is closely linked to the broader challenge of overcoming resistance to policy and administrative modernisation. Most tax systems in developing countries have sought to progressively increase reliance on voluntary compliance and risk-based auditing with at least some success. By contrast, Bangladesh has largely maintained a 'control'-based system, relying largely on the physical monitoring of taxpayers to enforce compliance. This has allowed tax officials to retain substantial discretion, thus nurturing opportunities for collusion with, or extraction from, taxpayers.

A high degree of administrative fragmentation exacerbates the basic inefficiency of the system. There has been a trend in many developing countries toward greater integration across administrative units. Unfortunately, the tax authority in Bangladesh remains divided into three highly autonomous divisions based on the type of tax rather than tax functions: direct tax, VAT, and customs. The relative absence of information-sharing across these departments severely undermines administration and sustains room for collusion, arbitrariness, and abuse.

Enforcement mechanisms are weak, reflecting in part the ability of large taxpayers to use political influence as well as malfunction within the judicial system. Lower levels of the appeals process are characterised by widespread potential for abuse, while cases that escalate to the higher courts are subject to high costs and inordinate processing delays. The latter has offered an informal means of tax evasion as no taxes are collected while cases are pending.

Significant human resource constraints within the National Board of Revenue (NBR) aggravate the challenges. Hiring is subject to common civil service recruitment through the Public Service Commission. Hiring of staff with the specialised skills necessary for modern tax administration is extremely difficult.

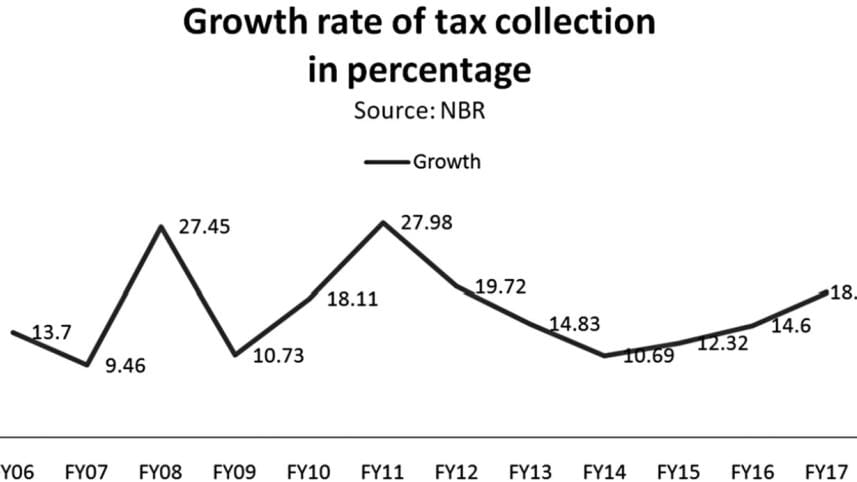

What is most remarkable about the long-recognised limitations of the tax system is its resistance to fundamental change despite many reform endeavours. The NBR has introduced taxpayer identification numbers, online tax filing, Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) and has expanded the tax net for small firms through innovative measures like tax fairs. These incremental reforms have contributed to noteworthy revenue gains. However, the broader reality is that incremental reform has generally been achieved where it has not threatened the incentives of leading interests. More fundamental changes have faced unfaltering resistance. Postponement of the implementation of the new VAT law in 2017 is the most recent instance of such successful resistance.

The unusual persistence of resistance to tax reforms in Bangladesh is striking. Not only does the tax system fail to generate significant revenue for the government, but extremely high levels of corruption and discretion within the system are anathema to the desire amongst businesses for predictability and low rates.

Yet, notwithstanding political commitments for fundamental reforms, there are vested groups in the business community and tax administration who would like to maintain the status quo. A poorly managed tax system will perpetuate structural inefficiencies and inequalities as well as under-funding of state operations essential for building a healthy society.

Zahid Hussain is an economist.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments