Bangla at the crossroads of recognition – a philatelic narrative

The 1940s was a turbulent time in the Indian subcontinent; shortly after the end of World War II, the peoples' demand for freedom was ever high and division of the land between Pakistan and India seemed inevitable.

Even before the formation of Pakistan, the probable difficulties facing the new nation were being addressed and the matter of the State Language was in the forefront. In an article appearing in The Daily Azad, noted educationist and linguist Dr Mohammed Shahidullah challenged the advocacy of Urdu as state language over all other spoken tongues. He, along with other figures and parties, rejected all discriminatory rhetoric regarding the official language of Pakistan. They argued the one language policy will only marginalise the minority, the very notion that the new country was hoping to eradicate.

Following separation, the language debate continued resulting in the initial days of resistance in 1948 - the one language policy being advocated and somehow forced upon the inhabitants of East Bengal (later termed as East Pakistan).

In his maiden visit to the eastern wing of the country, the founder and Governor-General of Pakistan, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, arrived in Dhaka on 19 March 1948. At the height of civil unrest and public opposition, on 21 March, during a public meeting at the Racecourse Ground, he gave his historic speech in front of a crowd with high expectations.

He went on to say, that the language issue has been raised to create a vision among the Muslims of Pakistan. Jinnah further reiterated the policy of the powers that be saying, “Urdu, and only Urdu” embodied the spirit of the Muslim nations.

Later Jinnah delivered a similar speech at Curzon Hall and on the radio. His stance was straightforward – an "Urdu-only" policy. He even retracted from the commitment made by Khawaja Nazimuddin with student leaders regarding the language issue. In 1952 the Language Movement saw renewed fervour and the fateful events of 21 February paved way for the establishment of Bengali as one of the state languages of Pakistan.

That was a history told time and again.

Disparity was a major issue. The very idea that the whole nation will have to comply with a language foreign to them gave rise to some practical problems. In our present times, when the Internet is accessible by the mass, it is quite difficult to fathom the impact of having only a single language in stamps, currency and so forth. It may seem quite a trivial issue but the matter was of great significance in those early days of Pakistan.

August, 1947. A new nation was born. As the two wings of the newly formed state celebrated separation from a colonial past, Pakistan Post Office issued a special postmark to commemorate the event.

'Long Live Pakistan' it read - in English and Urdu; without incorporating Bengali, or any of the other languages of Pakistan irrespective of the fact that Urdu was never spoken by the majority of the populace.

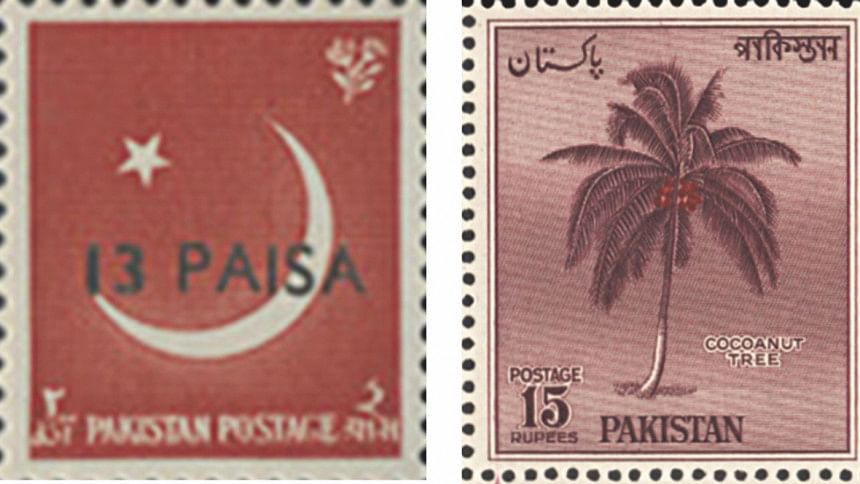

The first postage stamp of Pakistan featuring Bengali was not issued till 1956, some good eight years after independence; a stamp depicting the country's emblematic crescent and star, and a rose along with a distorted '2 Anna' inscription in Bengali.

In an attempt to trace the history of Bengali language through footprints of philately, it becomes evident that although postage stamps featuring Bengali first appeared in 1956, philatelic documents related to Bengali language dates far back.

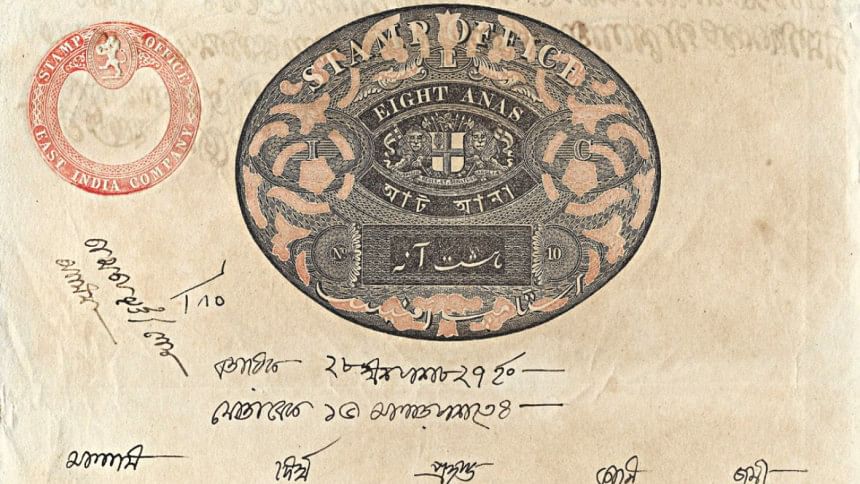

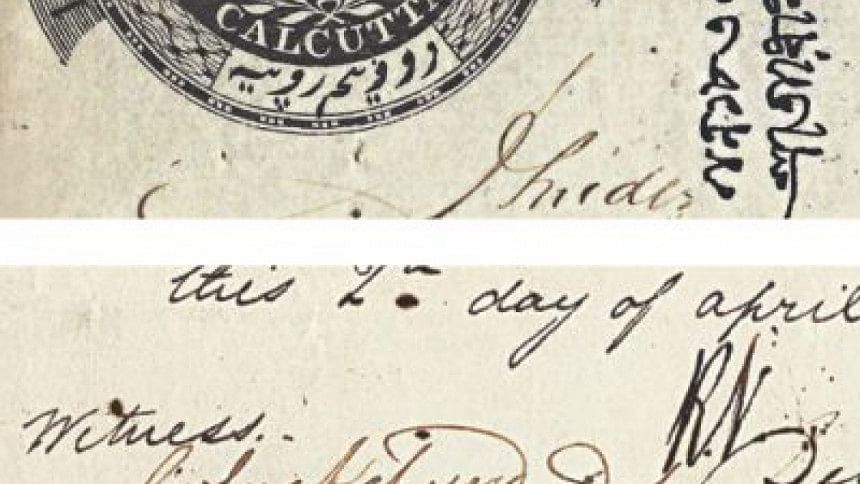

In the field of specialised stamp collecting ('philately' as it is called), although the focus is primarily on 'postage stamps', other stamp-like objects, revenue stamps for instance, are also deemed collectible. And possibly it is in revenue philately that the first documented use of Bengali is noted. Specialist collectors have in their possessions documents written in Bengali, some dating as early as the reign of the East Indian Company, when Bengal was a Presidency. Although Persian was the official language, court documents in Bengali scripts are known. The language of the people, as it seemed, was simply accepted.

Tax reforms were made under the East India Company and revenue stamped paper initially issued. As the methods evolved so did means of collecting tax and between c.1800 to 1873, Bengali was featured on stamped papers of the Bengal Presidency. The same measure was continued after the shift of power from the East India Company to the Crown.

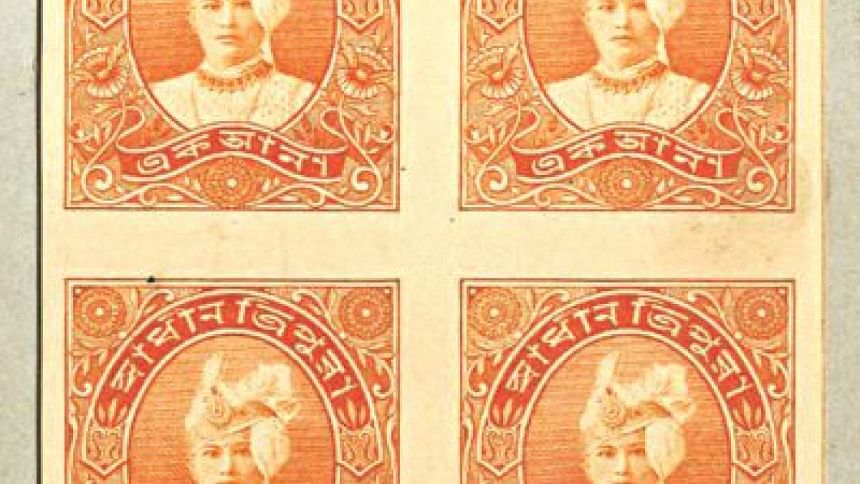

It is interesting to note that Princely Indian States of Tripura and Cooch Behar issued their own revenue stamps in the mid-1930s. Some of these were printed from renowned printers of England, while others were produced locally. The aesthetically beautiful stamps of Tripura and Cooch Behar lay testament to the fact that these States had considerable prominence and they highlighted their mother tongue with due fervour.

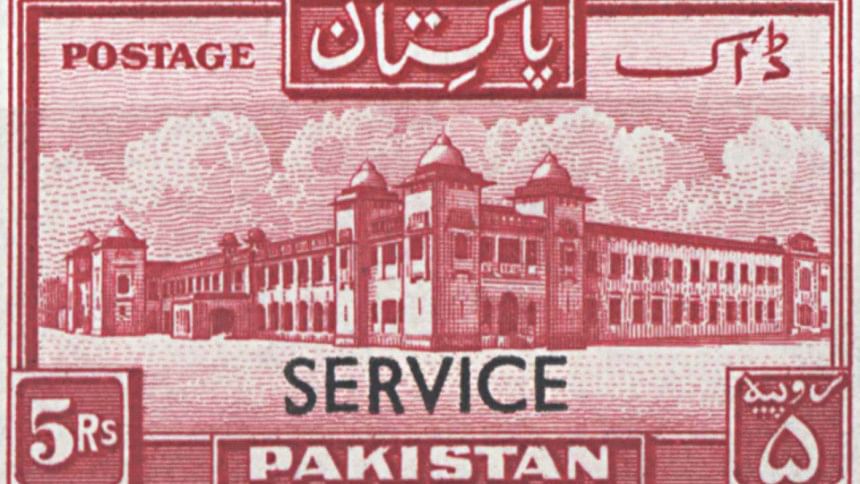

Although measures were taken to print stamps of Pakistan since day one, the government had to resort to overprinting British Indian stamps with the words 'Pakistan' in English. Unfortunately the entire consignment was damaged in an arson attack. Thus, the Pakistan Post Office decreed the use of hand-rubber stamps to overprint the word 'Pakistan'.

On 1 October, 1947 official overprints were introduced, which bore text only in English.

While Mohammed Ali Jinnah made it clear that Pakistan's official language would solely be Urdu, in 1956 Bengali was given the status of official language.

One cannot deny that Pakistan did have stamps focusing on East Pakistani themes, but the fact that the first inclusion of Bengali took eight years is simply astounding. And given the fact that first words '2 annas' were in a deformed Bengali script adds to that astonishment.

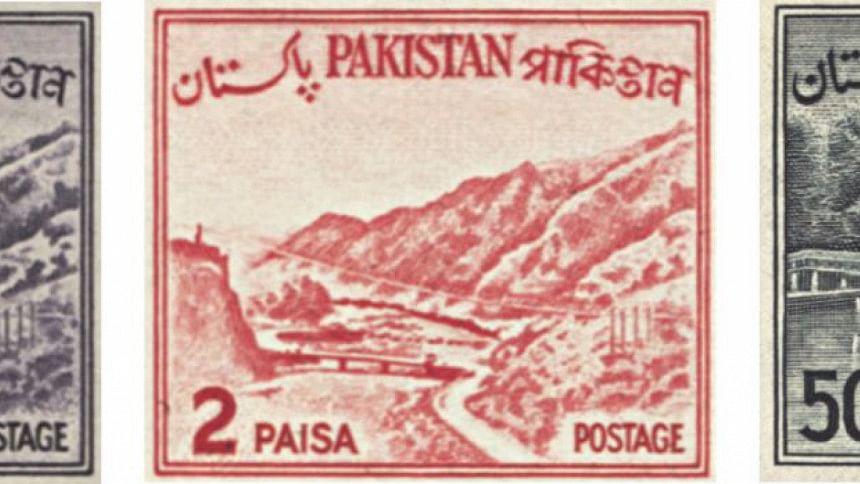

In 1962, when Pakistan moved to decimal currency a set of three stamps featuring the Khyber Pass was issued in one paisa, two paisa and three paisa denominations. All stamps featured the word 'Pakistan' in a distorted form - the Bengali letter 'Sha' replacing 'Pa'. Thus, 'Pakistan' became 'Shakistan'! Despite fervent criticism these stamps were not withdrawn; various retouches to the die were made before issuing the stamps in the corrected script.

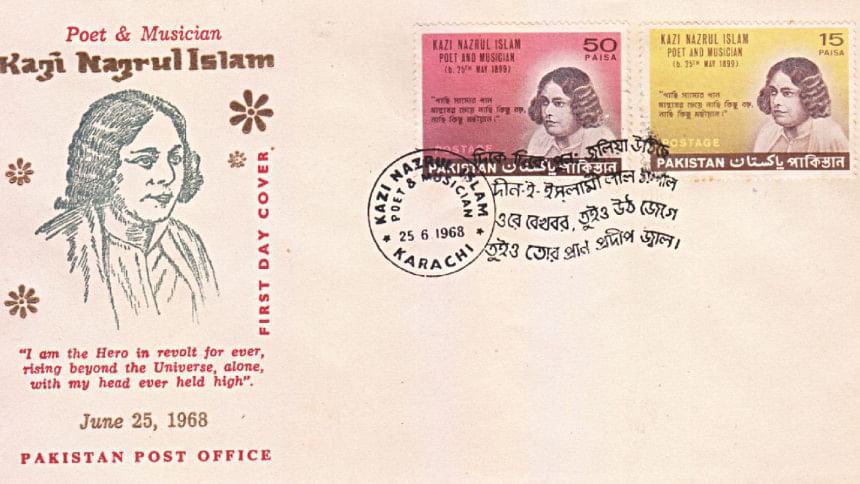

According to Banglapedia, during the 24 years (1947-1971), Pakistan issued 296 stamps, of which only 51 were with subjects related to East Pakistan. Up until 1971, only one Bengali personality, Kazi Nazrul Islam, was honoured.

This too, however, was also not free from controversy!

The stamps, scheduled to be issued to commemorate the poet's birth anniversary in May, were rejected before being put on sale because of an error in date. The new stamps were then issued with the necessary changes, yet the excerpt of the poem featured in the stamp remained incorrect. On 11 December 1971, the last stamp of unified Pakistan was issued in Dhaka.

Following the surrender of the Pakistan army, on 20 December, 1971 the Bangladesh Post Office became operational and orders were given to handstamp the words 'Bangladesh' in English and Bengali, on all postal emissions of the previous regime.

This continued till 29 April, 1973.

Language played an important role in shaping the political scenario of Pakistan and the resentment felt for an unbiased acceptance fuelled our strife for freedom. On 21 February, 1972 Bangladesh issued its first commemorative stamp on Ekushey February. Interestingly enough, this first stamp featured only Bengali! And quite aptly so.

Today's generation, growing up with all sorts of electronic communication methods, remains mostly unaware of the heritage of postage system and stamps. And consequently, a large source of history that remains tangibly withon our reach, often remains untapped or ignored.

For the layman from the slightly older gemeration, stamps evoke images of a romantic past, a childhood passion that involved fierce rivalry between friends in a quest to fill as many album pages as possible. Those who nurture this hobby beyond their teen days soon unravel that stamps, and everything related to it, are actually a witness of the past and the present, and 'philately – the study of postage stamps' is no mean feat, and certainly not a passé.

The writer is a Sub-editor at The Daily Star and a philatelist. Major references consulted were Bangladesher Dakbyabostha by Siddique Mahmudur Rahman, and Banglapedia. Special thanks to philatelists Mohammed Monirul Islam, Syed Ahsan Habib for providing images used here as illustration.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments