An unexplored facet of the language movement’s historiography

It is February 2002, the month of the fiftieth anniversary of our language movement. The contribution and inspiration of the language movement have been enormous in many of our cultural and political achievements during the past fifty years. The seed of our language-based nationalism started to grow from the very womb of the language movement. This view has earned almost universal acceptance in the historiography of our educated middle class. On the other hand, serious debates are still raging about the leadership of the language movement from different political positions. But no such debate is visible on the importance of the people's role. This is because, there appears to be unanimity that the task of the people is to follow the directives of the political parties or the political leadership. So where is the scope for such a debate? Debates can take place on issues such as the roles of various leaders in the movement or the accomplishments of different parties. Although these debates have not contributed much to our understanding of history, at least the names in the list of the language veterans have increased as a result. These veterans are quite well-known to us. They belong to the middle class, are university educated and overt or covert members of one or the other political party. The task of weighing them in the weighing machine of history started since 1952. Some have even resorted to fraud.

I want to discuss a neglected side of the historiography of language movement. For example, what was the role of the ordinary people, whom we call the 'public', in the language movement? And why did they participate in the movement on such a wide scale? If the birth of language-based nationalism is to be considered since 1952, then what was it like at the initial stage? I want to start a debate on these aspects after half a century, as much discussion on these questions could not be noticed in the past. Let us first take up the question of people's participation. Pakistan came into being in August 1947 as desired by the people. Before a year could elapse, the first clash on the question of language took place at Palashi Barrack of Dhaka city after 11 am in the morning of 12 December 1947. When a group of around 40 people riding a bus named 'Mukul' started to shout slogans in favour of-Urdu, someone from among the people who had assembled in front of Palashi Barrack and Ahsanullah Engineering College shouted slogan in favour of Bangla language. Reacting to this, the passengers of the bus, who were however described in the official report as hooligans, attacked the assembled people with sticks. The names of those injured, as found in the official records, were the first victims of repression in the language movement. They included one guard, four cooks, two students and the rest clerks of government offices. It is possible to conclude from this description about the social and economic status of those who protested and faced repression.

Next came the clashes of 21 and 22 February 1952. Let us look at the list of martyrs in those incidents. Abul Barkat was a student. Rafiquddin used to work in his father's press. Abdul Jabbar was the owner of a small shop while Shafiqur Rahman was an employee of Dhaka High Court. Wahidullah was the son of a mason and Abdul Awal a rickshaw puller (although the latter two were claimed to have been killed by motor accident in the official records, the cause of Wahidullah's death was mentioned as 'bullet wounds'). Besides, the diary of Tajuddin Ahmad dated 22, 23, 24, 25 February 1952 mention about spontaneous strikes of the people. That means, strikes were observed in Dhaka and elsewhere in the province without directives from any leader or organization. The 'Shaheed Minar' was erected on the night of 23 February. The then student of Medical College - Sayeed Haider - who was the designer of this Minar, had mentioned that apart from two masons, many canteen boys gave hands for completing its construction. They were the core workers of that time.

An important event took place on 29 February when the Head Mistress of Narayanganj Morgan High School, Momtaz Begum was arrested for actively participating in the language movement. While a large number of people, obstructed the police van when it approached Chashara station, she was being transported to Dhaka after her arrest. Badruddin Umar wrote that a large number of those who obstructed the police van were 'ordinary people' who did not have the capacity to educate their children at Morgan High School. Why did such a huge number of people resist Momtaz Begum's arrest? The clashes with the public became so widespread after the 21st that the government was in a way forced to concede to the demand for language.

At a time when 85 percent people of East Bengal were illiterates, why did the ordinary people join this movement for language rights? What was the linkage in the unity of the illiterates and the educated middle class? And what was the level of people's participation? This is the subject of my discussion. Was the language movement such a pure gold that there was no blight in it? Should not the drumbeat of one or two accomplishments of the ordinary people become audible amid the crescendo of glory surrounding the role played by the educated middle class? Was there any other question related to the mobilization of people in the language movement? Has any experience been preserved on this braiding in our national archives or in the experiences of the living, which contradicts the myths, especially those created after the emergence Bangladesh as a nation-state? If these questions are explored, then we can get an idea about the role of the 'illiterate', 'ignorant' and 'superstitious' collective called the 'public', their inherent nature and above all their consciousness. Badruddin Umar, who has authored three documentary volumes on the language movement, holds the view that the way this movement spread to the villages outside Dhaka proved that a deep concordance was already established between the social, economic, political and cultural problems of the people and the language movement of 1952. Our historiography lacks a logical explanation of how this unity was achieved.

I shall only attempt to offer a preliminary explanation of how the protests by the educated middle class and the illiterate peasants and labourers were woven together. It has been proved in recent research on nationalism that in pre-capitalist societies the contradictions that exist between the state and the peasantry create space for the elite aspiring for state power to unite with the latter. This aspect should be considered seriously while exploring deeply the question of participation of the masses in the language movement.

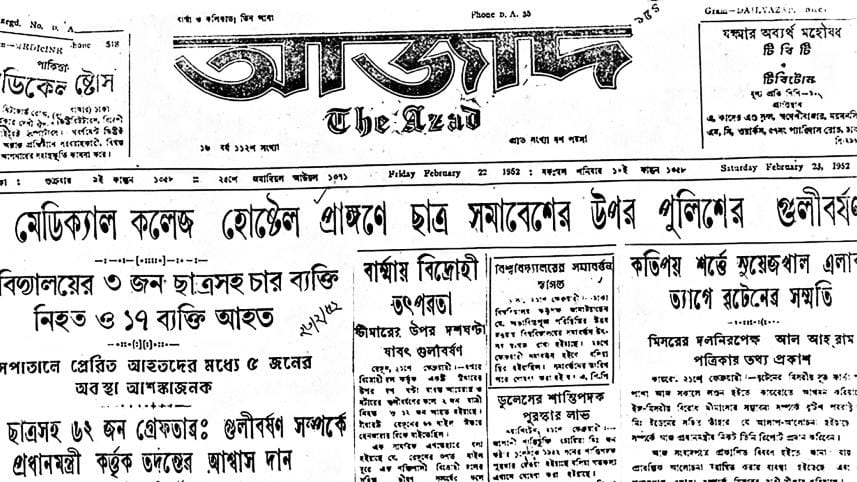

People's disillusionment with the food policy, market price of agricultural commodities, the behaviour of bureaucrats and the members of law enforcing agencies - especially the police - in the newly created state of Pakistan are important inputs for our discussion. We know that the cordon and levy systems introduced throughout East Bengal following food-shortages after 1947-made the life of the peasants miserable. Added to this was the repression of the police and the bureaucracy. The nature of police repression would be apparent from a few statistics. On the pretext of maintaining law and order, the police opened fire at the public 38 times in 1948, 90 times in 1949, 110 times in 1950 and 50 times in 1951. Descriptions of police-people clash during this period abounds in official records. There were reports of people- police clash even on flimsy grounds. From a news-item published in the 16 October 1947 issue of 'Dainik Azad', it could be gathered that around 3000 people had taken away from police 200 boats earlier seized for breaking the cordon law. Descriptions of many such incidents are found in the official documents of the period.

In 1952, the police engaged in maintaining law and order had almost lost their legitimacy among the people. On the other hand, the agricultural economy was facing a disastrous situation. Late Tajuddin Ahmad has mentioned in his diary dated 29 February 1952: "Jute price unusually went down since middle of February, from an average of 40/- P.M [per maund]. top and 28/- P.M. bottom to 25/- P. md top and 15/- P. md bottom. Last year in these days any kind of jute was about 50/- per maund, upto 65/- highest in village markets". Tajuddin Ahmad also mentioned that the middle and lower middle class peasants were seriously affected due to the wrong policies of the government. He further observed that a deep frustration pervaded the minds of the peasants from the middle of February. On the other hand, the price of rice was very high similar to the previous year. Rice was being sold at Taka 15 per maund. Tajuddin Ahmad wrote that the economic condition was disastrous. The state of the economy as described in his document and the actions of the police as evident in contemporary official documents make clearer the logic of spontaneous participation of the peasants and labourers in the movement of the educated middle class for the right of language. In such circumstances, it is not difficult to understand why the peasants and ordinary people were participants in the mobilizations of the language movement. But to appreciate the cause of unity between these two classes, the language, metaphors, imageries and heritage of protests should be comprehended properly. Above all, the nature of people's consciousness should be understood. I hope to inaugurate this discussion on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of our language movement.

Translated by Helal Uddin Ahmed. This article was first published in The Daily Star on February 21, 2002.

Ahmed Kamal is an eminent historian. He is a retired professor of history at the University of Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments