Why does infrastructure matter?

Ensuring better infrastructure ranked the top priority in the Dhaka Apparel Summit 2014 to reach USD 50 billion apparel export target by 2021. Indeed, the provision and development of infrastructure has been the subject of many theoretical and empirical studies. Economists have viewed infrastructure as a key ingredient for productivity and growth since at least Adam Smith. The role of transport infrastructure, for instance, in fostering economic prosperity goes back to Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations, which listed “the duty of erecting and maintaining certain public works” among the three (security, justice, and public works) core obligations of the sovereign.

How does infrastructure affect growth?

In this context, it is important to understand the empirical importance of the various transmission mechanisms through which infrastructure affects growth. The most conventional channel is productivity enhancement in the private sector. This direct productivity effect is the positive but decreasing impact on the marginal product of all factor inputs (such as capital and labour) from an increase in public capital stocks (relative to private capital). Consequently, the cost of production falls and the level of private production increases. This scale effect on output may lead to higher private investment, thereby raising production capacity over time and making the growth effect more persistent. On the other hand, in the short run, an increase in public capital stocks may displace private investment if it competes with private activity. This negative crowding out effect of infrastructure may turn into a long-term negative effect if the decrease in private capital formation persists over time.

Investment in public infrastructure can also impact investment adjustment costs and the durability of private capital. Adjustment costs are foregone profits from disruptions caused by the investment process. Infrastructure may reduce investment adjustment costs through complementarity between public capital and private investment and through the decreased costs associated with capital reallocation between sectors. Maintaining the quality of public infrastructure may positively affect growth by improving the durability of private capital. That is, increasing government infrastructure maintenance spending allows the private sector to spend less to maintain its own capital and thus to allocate its investment capacity to other uses, thereby generating an additional growth effect.

Better infrastructure improves access to health-care and education which magnifies the growth impact of public infrastructure due to the interconnected relationship between education and health. Healthier individuals tend to study more, while more educated individuals also tend to be healthier. Both contribute to increased labour productivity and hence growth. Better access to infrastructural facilities means that workers can get to their jobs more easily and perform their job-related tasks more rapidly.

Variation in the effects of infrastructure could arise from many other sources. When the available stock of infrastructure is low, investment has the same productivity as non-infrastructure investment. On the contrary, when a minimum network is available, the marginal productivity of infrastructure investment is greater than the productivity of other investments. This is known as the network effect. When the main network is achieved, its marginal productivity becomes similar to the productivity of other investment. These imply that other things equal the percentage increase in real GDP that results from a given percentage increase in the availability of infrastructure is roughly similar across countries irrespective of size, income level, or infrastructure endowment. Hence the marginal productivity of infrastructure is higher, other things being equal, where the (relative) stock of infrastructure is lower. For instance, if the ratio of infrastructure capital to GDP doubles, the marginal productivity of infrastructure is halved. The strong network externalities connoting many infrastructures call for a proper consideration of the co-ordination issue. Studies have also found evidence of positive externalities induced by public infrastructure, including increased competitiveness, greater regional and international trade, expanded FDI, and higher profitability of domestic and foreign investment flows.

What is the evidence?

There is increasing empirical agreement on the growth-enhancing effect of infrastructure. For instance, 32 of 39 studies on OECD countries find a positive effect of infrastructure on some combination of output, efficiency, productivity, private investment, and employment. Moreover, 9 of 12 studies on developing countries indicate a significant positive impact. In addition, government capital expenditures as a share of GDP are positively and significantly related to per capita income growth across a panel of 30 developing countries over the 1970–1980 periods.

For the most part, the empirical literature focuses on quantifying the impact of infrastructure on aggregate performance. It is silent about the specific channels through which the impact occurs. Although the findings are far from unanimous, a majority of studies reports a significant positive effect of infrastructure on output, productivity and their growth rate. This is mostly the case with studies using physical measures of infrastructure stocks. The results are less conclusive among studies using pecuniary measures such as public investment flows or their accumulation into public capital. The reason is the lack of a close correspondence between public capital expenditure and the accumulation of public infrastructure assets or the provision of infrastructure services, owing to inefficiencies in public procurement and outright corruption.

Empirical estimates of the magnitude of infrastructure's contribution display considerable variation across studies. Overall, however, the recent literature tends to find smaller effects than those reported in the early studies. This is a result of improved methodological approaches, at least in part. Thus, the mid-point estimate from recent studies of the elasticity of GDP with respect to infrastructure capital is around 0.15 for developed countries. This means that a doubling of infrastructure capital raises GDP by roughly 15 percent.

Estimates from recent studies using broader country samples are not very different. However, they capture only the direct effect of infrastructure on output, given the use of other productive inputs. There may be additional indirect effects accruing through changes in the usage of the other inputs due to complementarities with infrastructure. Studies based on panel data combining industrial and developing countries suggest that a 1 percent increase in physical infrastructure stocks, given other variables, temporarily raises GDP growth by as much as 1-2 percentage points. The growth acceleration gradually tapers off as the economy approaches its long-run per capita income. A number of empirical studies also find that the output contribution of infrastructure exceeds that of conventional capital, which suggests the presence of externalities associated with infrastructure services.

It is important to keep in mind that the bulk of the empirical literature is concerned with measuring the returns on infrastructure assets in terms of output, but has much less to say about the cost of acquiring and operating them. Assessing the latter is necessary to reach conclusions about the optimal level of infrastructure provision, achieved by equating marginal social return and cost, and to determine accordingly whether infrastructure is under- or over-provided.

Infrastructure investment is critical for growth

The bottom line is this: There is an increasing consensus that infrastructure, by raising labour productivity and lowering production and transaction costs, is beneficial for economic growth. Hence, infrastructure investment presents a powerful tool that policy-makers can use to reduce poverty and raise living standards. At the same time, investments in transport, water, sanitation, irrigation, telecommunications and energy can directly improve the welfare of the poor simply by providing access to basic needs.

These conclusions are subject to two caveats. The first is reverse causation. The output impact of infrastructure supply that empirical studies aim to capture may be confounded with the impact of higher incomes on the demand for infrastructure services. Failure to take this feedback effect into account likely results in an overestimation of the output contribution of infrastructure. The second concerns heterogeneity. The output contribution of infrastructure may well vary across countries and time periods depending on many factors, starting with but not limited to the heterogeneous quality of infrastructure assets themselves. Not many studies are able to take into account the quality dimension due to measurement problems. Those that do, find that the quality of infrastructure is no less important than its quantity for aggregate performance. One policy implication is that adequate maintenance of existing assets deserves at least as high a priority as the acquisition of new ones, a lesson often forgotten, especially in developing countries.

How much investment does Bangladesh need?

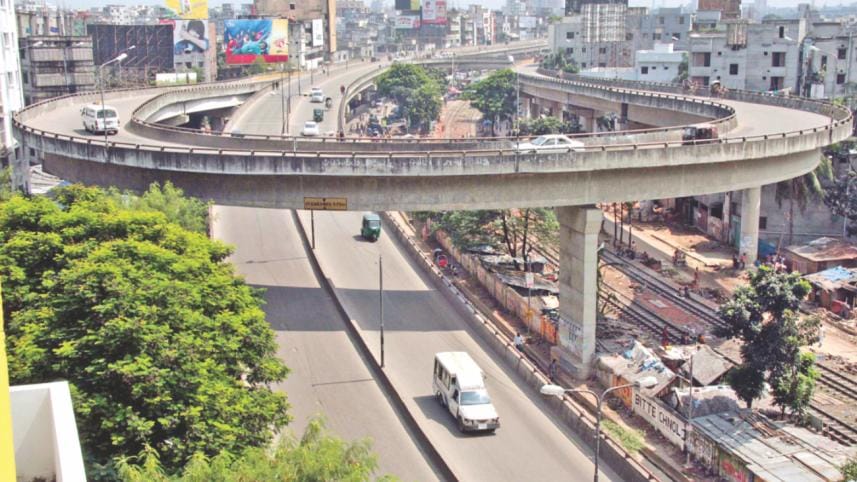

The current generations in Bangladesh have inherited infrastructure stock built by previous generations. With growth both the type of infrastructure and the quality of service provision has evolved. There remains a very large infrastructure gap. Bangladesh has one of the worst access rates to infrastructure in South Asia. It has the worst coverage of paved roads and is only better than Afghanistan in terms of access to telecommunication, electricity, sanitation, water and total road network.

How much money will be needed to close Bangladesh's infrastructure gap?

The World Bank (2013) estimated that Bangladesh needs to invest USD 74 to USD 100 billion in infrastructure until 2020. In terms of GDP, if infrastructure investments are spread evenly over the years, Bangladesh needs to invest between 7.4 to 10 percent per year. Note that average infrastructure investment as a percentage of GDP hovered around 6 percent for Bangladesh, India and Pakistan and 5 percent for Nepal for the period 1973-2009. A mix of investing in infrastructure stock and implementing supportive reforms will enable Bangladesh to close its infrastructure gap.

A significant share of the infrastructure investment in the near and medium term will have to come from the private sector. Some sectors such as energy and telecom have drawn a lot more private sector interests than others. In transport, the private sector preference appears to be partnering with the public sector through Public Private Partnerships (PPP) while it prefers to invest by itself in telecommunications as well as energy.

A key question is prioritisation. How much financial resources should be allocated to infrastructure development overall vis-à-vis others such as public safety, health and education and within infrastructure sectors? Unfortunately, there is no golden rule to decide the allocation. Considering that infrastructure is both a means to facilitate economic growth as well as a measure of development itself, it is fairly straightforward to conclude that a higher share of GDP needs to be allocated to infrastructure.

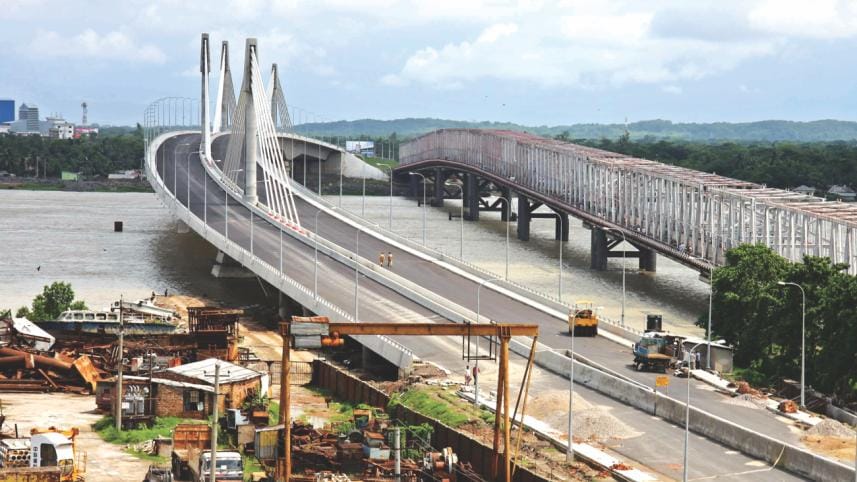

The dichotomy between prioritising large-scale infrastructure and addressing the needs of the poor is false. Many large scale infrastructures facilitate economic growth and enhance welfare of the poor. A large transport project such as the Padma Bridge may primarily target facilitating trade within the country, but at the same time it will also connect isolated poor populations to better services.

Walking the talk

Closing the infrastructure gap is a top priority for Bangladesh. There is no need to debate that. Infrastructure is a major hindrance particularly in transport and electricity. Policy makers do not have to choose between growth and inequality of provision; there is enormous potential for them to be mutually supportive. These are very well recognised in Bangladesh. Question is how to get it done. One way is to give the private sector a bigger role through PPPs or regulated privatisation and market liberalisation. Giving greater administrative powers and functions to lower levels of administration and government is another way. The optimal mix of these options depends on the nature of the investment, the reason it is provided, how it is financed, and where it is located.

What we need is to walk the talk.

The writer is Lead Economist, The World Bank, Dhaka

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments