Finding the superbug, the invincible bacteria

Cover: Kazi Tahsin Agaz Apurbo

Let us cut to the chase. The superbug exists among us and scientists have discovered a rather frightening phenomenon around our city hospitals.

The 'superbug' is the media-savvy name given to any bacteria that is resistant to all (or almost all) types of antibiotics. This means a simple pneumonia can take a turn for the worse when it cannot be treated with the regular broad-spectrum antibiotics.

"We tested water samples from areas beside different hospitals in the city and found bacteria encoding genes that make it resistant to the most potent class of antibiotics known as carbapenems," says Dr Mohammed Aminul Islam, the lead scientist from International Centre for Diarrheal Disease Research, Bangladesh (ICDDR,B) who conducted the study in collaboration with Stanford University and Erasmus Medical Centre. The report was published two months ago in a journal called Applied and Environmental Microbiology.

Breaking down medical terms, carbapenems are antibiotics which are only given as a last shot when all else fails. So last-stage that they are not even taken orally, according to Dr Islam, "Carbapenems are usually administered via injection." Generic names of carbapenems in the market include meropenem, imipenem and ertapenem.

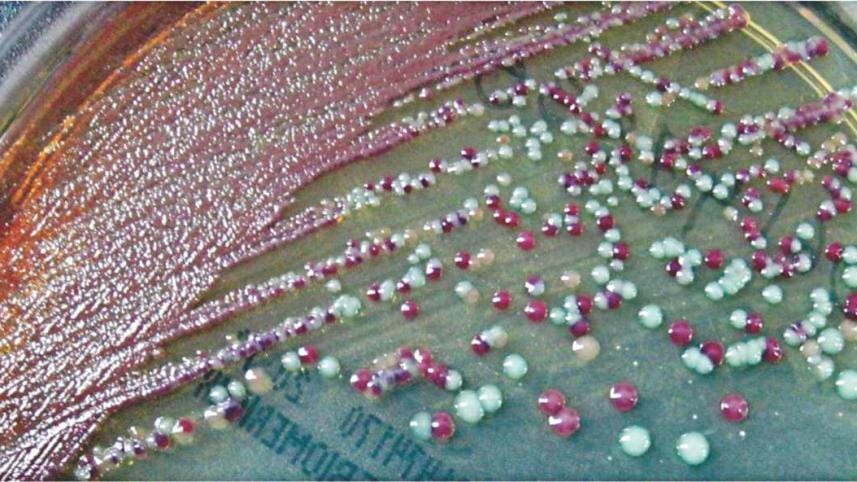

Scientists collected over a hundred wastewater samples from hospital adjacent areas and communities and found that about 96 percent of the samples had bacteria resistant to carbapenem. This included common bacteria like E.coli which gives diarrhea and Klebsiella pneumoniae, which as per the name, causes pneumonia. Both of these are notorious for spreading easily and quickly.

Although the researchers declined to specify which hospitals they collected the wastewater from, to maintain impartiality, the study covered areas adjacent to big hospitals in Mirpur, Mohakhali, Kotwali, Dhanmondi, Ramna, and Uttara.

"What this means is that hospitals are contributing largely to the dissemination of these bacteria to the environment and the people are getting exposed," says Dr Islam - and it is not only in theory, according to their observations. "We have previously found these superbugs in hospitalised patients with simple diarrhea," he adds.

Unfortunately the story is hardly over if anything it just began. Even with the knowledge that almost all the wastewater studied contained superbugs, what is perhaps more important is that half of all the samples were positive for bacteria capable of producing an enzyme that is infamous among scientists for how potent it is. The enzyme called NDM-1 (New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase 1) is what makes the bacteria resistant to carbapenems, but what scientists are more concerned about is that it spreads very fast and very effectively.

In fact, Dr Islam's research primarily set out to focus on NDM-1, and analyse exactly what level of threat we are dealing with. NDM-1 has a unique replication method. "One way that bacteria can spread is by reproducing and multiplying in numbers, but that is not the only thing happening here," describe Dr Islam, "Bacteria passes on the NDM-1 encoding genes to other bacteria it comes in contact with through a mechanism called horizontal gene transmission."

To put it simply, he explains, when a diarrhea patient with superbug E.coli comes in close contact with a patient with garden-variety pneumonia, it can turn the latter's disease lethal.

"NDM-1 exists as a mobile genetic element that it passes on to other bacteria of different species in the environment," says Dr Islam. Such mingling would usually happen in the environment— such as, if wastewater was collected from both the above-mentioned diarrhea and pneumonia patients and combined.

To test the mobility of the NDM-1 gene, the scientists pitted their samples against E.coli bacteria which was not resistant to drugs. About 27 percent of the sample carried forth the gene. They further tested to see whether it could spread from areas adjacent to hospitals to communities, the answer was a resounding yes.

"In the present study, we identified a number [of] rarely reported species as NDM-1 producers," states the report. "Most of these organisms have not been reported as NDM-1 producers from Bangladesh previously, such as Enterobacter asburie, Providencia rettgeri and Acinetobacter baylyi.

"These findings suggest that the gene encoding NDM-1 is spreading to non-conventional organisms and its distribution is more widespread in the environment than previously appreciated," the statement ends ominously.

"NDM-1 first appeared on the public radar after 2009 when a Swedish national visiting New Delhi contracted a urinary tract infection.

Upon returning home, the doctors found that no antibiotic was working," describes Dr Islam. The patient perished but the findings were made known to the scientific community.

"That is when 65 countries came together to screen for NDM-1. I did it with ICDDR,B here in Bangladesh and found samples of it in our diarrhea patients," adds Dr Islam.

This was absolutely new for the scientists, he claims. "Even if NDM-1 had existed in the environment, it was definitely not as prevalent. There is a rising trend of antibiotic resistance."

Medical waste mismanagement leading cause

Situated right across the stalwart gates of the Dhaka Medical College Hospital administrative building is a rubbish dumping point. An overflowing garbage dumpster sits on the road lording over heaps of trash on the street. Right behind it, Nadir Hossain and two other municipal cleaners sits on the grimy sidewalk, shaded by a tarpaulin propped up on the tarmac. "We are municipal cleaners—our job is to keep the street surrounding the dumpster clean," says Hossain. Judging by the condition of the street though, it seems as if Nadir and his colleagues have given up trying to contain the overflowing trash inside the dumpster.

At several points during the day steel gurneys (yes, the same steel gurneys used to transport patients) loaded up with yellow, green and black bins are rolled up to the dumpster. The bins are emptied into the dumpster and left to lie there until a ward-attendant takes them back, according to Hossain. Yellow signifies infectious waste, green is medicinal waste and black is normal, municipal waste—but once they all get poured into the same dumpster, it all becomes a cesspool oozing sludge into the neighbouring skip.

Ideally the waste is supposed to stay separated until the last stage of processing. But the vast piles of bloodied, iodised gauze and bandages, blood-bags, urine bags and needles suggest a different story. A ward attendant claiming to be from the dialysis ward pushes in a gurney of bins and snaps on plastic gloves he pulls out of his pockets so as to dump the bins, but sees our cameras and changes his mind and leaves. A dog trot up and sticks its muzzle into the mess, but whatever transmission it can do, the pack of roosting crows far outnumber it.

"Everyday at 6 am in the morning, a truck from the waste management company Prism comes rolling in to collect the trash," says Hossain. Just once a day? "Yes," he confirms, adding that the waste are taken to Matuail where Prism owns a plant specialising in medical waste management.

When contacted for an interview about the efficiency of the waste collection methods Prism declined to respond to any questions until their executive director comes back to town. "We collect all forms of infectious waste," says Nilufer Alam, manager of training and communications at Prism.

The incinerator at Dhaka Medical College Hospital has been out of service for several years, although the exact number is anybody's guess. A working in-house incinerator would have immediately solved the problem of the garbage dump outside. Almost as a way of things going back to nature, the dormant chimneys now lie hidden behind happily-growing greenery. Nasiruddin Nannu is the ambulance supervisor of the hospital and he parks his vehicles in the location adjacent to the incinerator room, "I've been working here since the 1980's, and trust me when I say that the incinerator has been out of service for the last six or seven years," he claims.

DMCH director brigadier general M Mizanur Rahman acknowledged that the incinerator is out of order. "Look, it's been like that since before I joined," he justifies over the phone, when asked about antibiotic resistance risks due to medical waste mismanagement. He has been serving by this position for two years now. The phone interview did not proceed.

The antibiotic resistance threat

Antibiotic resistance is a looming threat, all experts agree. Remember that last bout of lingering, persistent bronchitis that refused to get treated despite several rounds of antibiotics? Much of the population has faced small incidences of antibiotic resistance, according to doctors.

Dr Mohammed Mizanur Rahman, a medicine specialist general practitioner in the city professed his extreme frustration at the situation. "We are struggling to control simple ailments like diarrhea because of resistance," says Dr Rahman, "I have to prescribe higher and higher doses."

"The resistance is at such a level that we sometimes find it hard to treat normal typhoid with oral medicine," he adds.

Doctors do not always do proper culture and sensitivity tests before administering antibiotics which makes the bacteria increasingly resistant, says Dr Rahman. "Some empirical prescription can be done but this is the norm. In rural areas doctors never test before giving antibiotics. Speaking from experience, there are no facilities to do this test in the suburbs around Khulna city."

The last time this correspondent did a culture and sensitivity test for (afore-mentioned) lingering bronchitis from a private hospital, the report essentially showed zilch. The report simply identified that the patient tested positive for microbacterial growth in the upper respiratory tract. It did not identify what species of bacteria I was infected with, and by how much. Breaking down the medical terms, the report basically only provided a document saying I was sick - something I already knew! For a doctor, that non-specific document is what they would have had to base their diagnosis upon. Under such circumstances, how would a doctor know which antibiotic to prescribe?

"While antibiotic resistance is a global problem a large portion of the burden exists in developing countries where antibiotics are not used properly," says Dr Islam. He also mentions that since doctors do not supervise or coach patients, patients routinely fail to complete antibiotic courses, thereby giving rise to resistance.

The Center for Disease Control, a wing of the Directorate General of Health Services, has taken the problem into cognizance and started a programme in January this year to tackle the issue. The programme dubbed "Antibiotic Resistance Containment" has so far created a national plan of action, informs the CDC director Dr Sania Tahmina.

"In the plan we determined causes of rising resistance and are discussing a national strategy to tackle it," adds Dr Tahmina.

Among the intervention points, the officials are taking a look at just how antibiotic resistance grew as a failure in oversight. "There is the disposal of medical waste into the environment, and then, we have to curb the indiscriminate use of antibiotics in livestock, and we also have to control how pharmacies sell them over the counter," she says.

"This is the first time the government has taken an official position against antibiotic resistance," she asserts.

There is no quick-fix unfortunately, claim experts. This is a reality and the sooner we accept it and educate the community, the better.

"We are living in a cycle. We disseminate bacteria into the environment and it spreads resistance. We then take up the newly resistant bacteria and the cycle goes on," describes Dr Islam.

Can the cycle be broken? "Yes, by the rational use of antibiotics," he says. Once you take out the threat, the bacteria will lose the resistance, he ends simply.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments