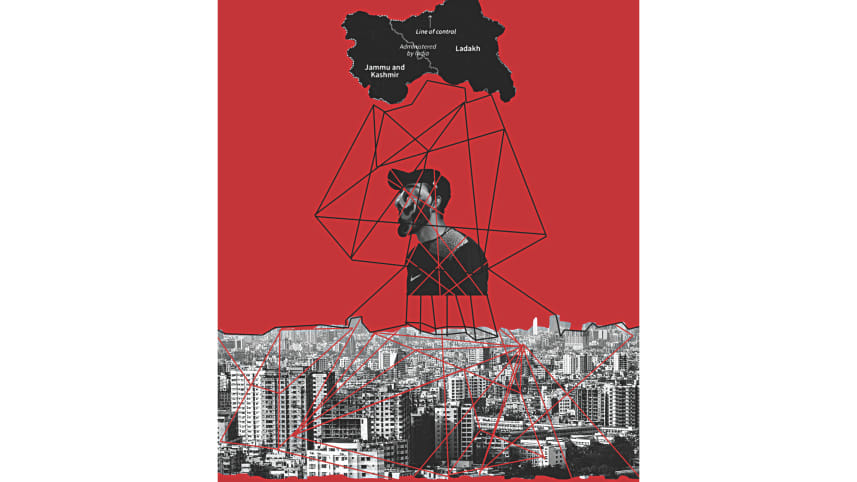

The issue of Kashmir hits close to home

Ahmad Shafi* sensed the unrest in Kashmir before it happened. An MBBS student in Bangladesh, he was in class at Dhaka's Green Life Medical College when he got the news that India had revoked the status of the semi-autonomous state of Jammu and Kashmir on August 6, imposing a blanket ban on all forms of communication.

"Something was coming. Everybody knew it. We have been in this environment for so long, we know the possibilities," Shafi says. "We can do the math and come up with the answers ourselves."

Two days before the Bharatiya Janata Party-led government removed Article 370 of India's constitution, guaranteeing their special status, Shafi's cousin called. He warned him of an impending struggle and transferred money to cover his living costs in Dhaka. His cousin feared this was the last time he would be able to send money for the foreseeable future. At the time, India was deploying large numbers of troops to Kashmir—they now number almost a million, turning Kashmir, already one of the world's most densely militarised areas, into a space of siege.

Tens of thousands of Kashmiri students studying abroad were cut off from their families that day. Many depend on their parents to send money once or twice a month to cover their expenses, but with bank and internet access down, their funds are dwindling. Bangladesh was hit particularly hard with the communication blackout—parents in Kashmir have managed to call their children from government officials' numbers if they study in other Indian states, but unauthorised international calls are barred in Kashmir.

Across colleges, across locations, the story is the same, and the atmosphere is growing desperate. Shafi has not been able to contact his parents for over a month. He has no idea where they are.

"For the past few days, I've begun to have these nightmares, started to feel a bit panicky. I was trying to keep calm, but I couldn't," he says.

After a pause, he continues: "You have to be patient. You know, for the past 30 days, I haven't been able to forget my family. And if I'm not patient, then, it's actually quite depressing ... You have to keep going on."

Omar Rashid*, a student at a Gulshan medical college, also affirmed people came to know August 4.

"It's the same story with me," he says. "They tried to arrange it so we're not on our own. But so many are."

Rashid's only sources of information are international news outlets like BBC and Al Jazeera. He avoids national news coverage because he says they are normalising the situation.

"The whole world is crying for us. Still, nobody is doing anything," he says.

Though there are no exact statistics on how many Kashmiri students are studying in Bangladesh, English daily The Kashmir Monitor estimates around 500 students enroll in Dhaka's medical colleges every year. Dhaka serves as a hub for medical studies in particular due to both the low cost relative to India, making it affordable for middle-class families, and the familiarity of a Muslim-majority country. The actual number of Kashmiri students in Bangladesh is likely higher—Kashmiri students themselves place their numbers in the thousands.

Now, more than a month has passed and these students are strapped for cash, distraught and frustrated. Many have turned to their friends for loans, but this source of money is fast running out. Mohammed Dhar*, a classmate of Rashid's, runs an online platform with him to support Bangladesh's Kashmiri students, though he himself is struggling financially. Created earlier this year, it has taken off in the past month. Holding back tears, he said his rent is expensive, and he has resorted to the last of his pocket money.

"Whatever happens, we'll manage it ourselves," Dhar says. "We've been there, we know the problems. We haven't gotten (help) from Bangladesh, but we have each other."

Bangladesh's Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) has dubbed the abrogation of Article 370 "an internal issue of India", advocating that as a matter of principle, maintaining regional peace and stability should come first. The statement comes one day after India's External Affairs Ministry held meetings with Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina and the head of the MFA.

Dhar says he never thought of going to his university for financial support. For him, the institution means the government, and therefore has little to offer in terms of protection. "They don't support us. They didn't give any response," he adds, referring to the MFA's statement. "(The university) just said, don't (protest) here. This is your final warning."

All three students have participated in protest efforts from Bangladesh, but have seen it is to no effect. "I saw the report from some minister saying it is an internal matter of India. We tried to protest here, but we could tell that the ministers were uncomfortable. You could see it from their faces," Shafi said.

Despite the government's neutrality, Dhaka has been a stage for protest in the past month. Four hundred Kashmiri students gathered at Dhaka University on August 8, not only to peacefully demonstrate against Indian oppression, but also call on Bangladesh for explicit action and solidarity. The students chanted slogans and carried banners calling for the immediate restoration of internet, landline, and mobile networks, marching in the rain all the way to the Shaheed Minar.

Even before August 6, Rashid and Dhar missed the comforts of home. Though they were quick to extol of the virtues of Bangladeshi people, they said they had a difficult time adjusting to the food, city life and temperature. At college, they mix with both Bangladeshi and the 50-odd Kashmiri students studying with them, finding solace in their friendships. Lots of people are childhood friends who come here, knowing each other from Kashmir, Rashid says.

These students are making efforts to connect in this time of struggle. Left without their lifelines, they meet at their colleges and across campuses and discuss rumours of killings—taking care to do it in person, never online. This community has leaned on each other in more ways than one, supporting each other not just financially, but emotionally. Enrolled in vigorous programs, missing their families and worried about their homeland, this period of unrest has taken a severe toll on their mental health.

"From that day, (the killings) are all we can talk about. We are disturbed. Depressed," Dhar says.

"It's complete mental torture," Rashid adds. "We can't talk because we are afraid. We are far from home, in a random place."

The state of fear and insecurity these students face are in our country's jurisdiction to, if not fix, then to at least mitigate. There must be space for this conversation to be had. Other than the first gathering in front of the Shaheed Minar (after the troops were first deployed in Kashmir), there has been no other noise from local Kashmiri students, even though the situation is ongoing, and for them, increasingly dire. As the tension wears on, they are growing more afraid to speak out about their struggles. It's not safe, both Dhar and Shafi echo.

"I want to go home to Srinagar, work as a doctor in Kashmir. In Indian-occupied Kashmir," Dhar clarified, laughing slightly. "We are waiting for the day we can go back. Kashmir is like heaven on earth. It's mountains, it's nature, it's water, it's fresh air. It's sacred."

*Names of the Kashmiri students have been changed.

Rayna Salam is an intern at Star Weekend. She is studying International Development and Statistics at the University of California, Los Angeles.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments