The One About Friends

Seven thirty pm on Star World was when it began for me. I was young—too young to be watching Monica and Chandler kiss, to get Joey’s flirty jokes, or to understand what was at stake when a livid Rachel asks Ross of the girl at the copy machine, “How was she?” I watched Friends because I had no siblings and only hung out with my (then) teenage aunts and uncles. They loved Friends, and to “get” Friends would mean I was a part of the young, ‘cool’ adult world tantalisingly beyond my reach around me. Its fumes of syrupy sarcasm and happy-go-lucky attitude towards life I absorbed like a passive smoker.

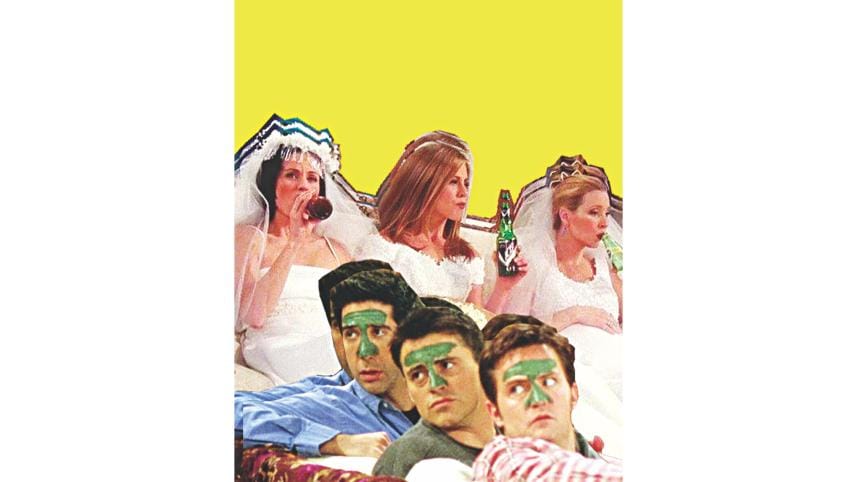

And so I learned to love the show before I’d even really watched it, as is the case for many of its current fans. Friends aired on NBC from September 22, 1994 to May 6, 2004. That makes it 25 years old this year, in two days. But here in Bangladesh, the show made its mark through endless reruns on Star World and later Comedy Central before hitting Netflix.

It seems redundant to try to pinpoint why people love Friends. As a recent New York Times tribute pointed out, Friends was ‘easy’ television—the plots were simple and wholesome (as were the sets) even in portraying tragedy, the (allusions to) sex at a healthy PG 13, and the humour even more so. True love, good karma, happy endings, glossy hair, perfect bodies. It made casual comfort look pretty and attainable, and so invited generations of viewers, time and time again, to seek solace in Monica’s purple apartment and Central Perk’s cosy brown interior.

As for many, however, watching Friends now is an odd experience fraught with some shame, disappointment, and sometimes outright shock at some of its content.

Ross is made fun of whenever he tries to talk about anything “intellectual”, not just his job as a paleontologist. In “The One Where Phoebe Runs” (season six), he shares, “I just finished this fascinating book. By the year 2030, there’ll be computers that can carry out the same amount of functions as an actual human brain. So theoretically you could download your thoughts and memories into this computer and live forever as a machine.” Fascinating stuff. Chandler’s reply? “And I just realised I can sleep with my eyes open.”

Later in the same season, Ross, who believes it’s too “soon” for Elizabeth and him to take a trip together as a couple, crashes her spring break trip with her friends after deeming her travel group too all-male and her swimsuit too skimpy. “Okay, she can’t go,” he suddenly decides for her. The show is peppered with such misogynistic incidents—Ross deciding how and with whom his girlfriends can socialise, Joey objectifying and dismissing women, Rachel, Monica, and Phoebe resorting to kissing each other or flashing in front of the men to get their way.

It’s worse than revisiting old childhood favourites (like old Nickelodeon shows or Sweet Valley books) and realising that you’ve outgrown them; because Friends isn’t children’s television. It’s therefore that much harder to process that an entirely adult cast of characters showcased, and a mostly adult audience accepted, for a decade, the blindingly white cast, a steady mocking of intellectualism and fluid gender norms, and a reinforcement of the societal pressure to find love, get married, be appropriately feminine or masculine.

It did, however, get some things right.

The show pilots with the fall of Ross’ marriage. His ex-wife Carol has turned out to be a lesbian and fallen in love with a woman named Susan. The screenplay, for several episodes, is rife with jokes cast at Ross for being in a situation so painful that it’s funny. She was his wife of many years, after all. But note that at no point does the screenplay make fun of Carol and Susan for being homosexual. Cast against the other characters’ many turbulent relationships, Susan and Carol are portrayed as the strongest, most stable, most mature two people in love. They are utterly content in their decision to be together through all the seasons.

A similar portrayal surrounds the friends’ parents. Rachel is shocked to see her mother embracing her divorce and a younger, happier lifestyle. Chandler is endlessly ashamed of both his brazen mother and his transgender father who performs at an all-male burlesque club. In both instances, while others view these non-traditional life choices with derision, the characters themselves own their decisions completely. Their choice of lifestyle never wavers in the plot. For a show so vastly swept by homogeneity and heteronormativity, it’s worth noting how the comic screenplay seems to reflect the traditional stereotypes of its time—revealing the flaws in the people of its time—while the underlying narrative challenges them.

Over the years, I’ve come to realise that my respect for Friends doesn’t stem from the comfort or happiness it induces with each episode; it comes from the frustration it makes me feel often.

Growing up, I always disliked Phoebe. I disliked her most in “The One with the Fertility Test” (season nine), when Rachel receives a gift certificate for a spa massage, but isn’t allowed to use it because Phoebe swears against such chain massage parlours. It hampers business for struggling masseuses like herself, Phoebe argues, even though she secretly works at that chain. A similar irritation arises when I watch “The One with the Apothecary Table” (season 6), in which both Ross and Rachel have to hide their furniture purchased from Pottery Barn, which Phoebe also hates. Furniture should come with a unique history that is often lacking in mass produced goods, she believes.

I respected Phoebe’s views, even agreed with them personally. But it irked me that those around her were having to reshape their own preferences, their own lifestyles, just to satiate a friend, especially when that friend was herself so unsure of her beliefs. (Phoebe ultimately gives in to the Pottery Barn craze. In another episode, she grudgingly settles into a mink coat she initially swears against). It felt like too big an encroachment on one’s personal space, something that I noticed many of the other characters practicing with each other often.

But the point of the episode’s plot—and in fact of the entire show—shines through when Ross voices his annoyance with Phoebe. “Yeah but Pottery Barn! Y’ know what I think? It’s just she-she’s weird!” Ross shrieks. But Rachel explains to him, calmly: “Ross, she’s not weird, she just wants her stuff to be one of a kind.”

That simple act of acceptance—empathetic, matter of fact—is what forms the skeleton of all 10 seasons of Friends. All six friends bat it around when the situation demands it. Be it Monica’s obsessiveness, Phoebe’s whimsy, Ross and Rachel’s melodrama, or Joey consistently raiding everyone’s food supply, there is among them an unconditional acceptance of each other’s quirks, even when it’s all too often inconvenient. A decade-long intimacy with this show has helped me internalise not only the optimism and the wholesomeness of its comic situations, but also its easy embrace of all that is weird and different and difficult to absorb in others. It’s been a lesson in compassion, in weathering through the trickier bits of truly “being there for” someone.

That this show, with all its flaws and wonders, is an all-time favourite for more than an entire generation says a lot about those viewers. To grow up watching it in the 90s was to submerge oneself in the all-American dream in which careers bring about spiritual fulfillment, where lows always escalate to highs, where your friends always have time for you and true love wins the day. It’s a dream that makes the bluer days feel a tiny bit better when you turn on a random episode at night, during dinner, when you’re exhausted or cranky or miserable or simply bored. But to watch it now, in 2019, is also to realise that many of our most beloved things are often problematic. How much do we find ourselves resisting when we watch it now? How much are we willing to overlook, how much should we forgive?

Sarah Anjum Bari can be reached at sarah.anjum.bari@gmail.com

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments