Intertextuality in Shahaduz Zaman’s ‘Prithibite Hoyto Brihaspatibar’

Literature is essentially an art form woven from a web of other texts. When a reader engages with a piece of literature, it seamlessly integrates into their experiential elements. When transitioning to writers, this assimilation of texts becomes a conscious or subconscious incorporation, explicit or implicit in their creative process. Postmodern theorists, including Mikhail Bakhtin, Julia Kristeva and Roland Barthes, posit that every text inherently intertwines with others, embodying a phenomenon encapsulated by the term intertextuality. This phenomenon manifests when one text refers, quotes, or alludes to another, creating an interplay and interconnectedness between different texts. The term suggests that texts derive their significance within a broader contextual framework. Beyond serving as a theoretical lens for reading or interpreting texts, practical engagement with intertextuality—such as linking to or referencing other works—introduces nuanced layers of meaning.

It is worth noting that the practice of creating intertextuality has been around for much longer than the more recently developed theory of intertextuality. John Milton's 1667 treatise on the Fall of Man, Paradise Lost, stands as an exemplary intertextual work, recontextualizing The Bible through a new perspective: Satan's. William Shakespeare's famous play Hamlet (1603) draws inspiration from several sources, including the revenge tragedy tradition and Norse mythology, adding depth and complexity to the character and plot. James Joyce's epic novel Ulysses (1920) is filled with allusions to classical mythology, history, and literature, creating a complex network of references that enriches the reading experience. The rich tradition of intertextuality extends to Bengali literature as well. Michael Madhusudan Dutt's Meghnad Badh Kavya (1861) draws heavily on Valmiki's Ramayana and Homer's Iliad, creating a unique Bengali interpretation of the epic battle between Rama and Ravana. Rabindranath Tagore's Gitanjali (1910) often references religious texts, such as the Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita, enriching the meaning of his poems and allowing readers to connect them with broader cultural and religious traditions. Kazi Nazrul Islam's "Bidrohi" (1922) contains numerous references to historical figures and events, such as the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857 and the Bengal Renaissance, providing the poem with historical context and depth, while also invoking the revolutionary spirit of previous generations.

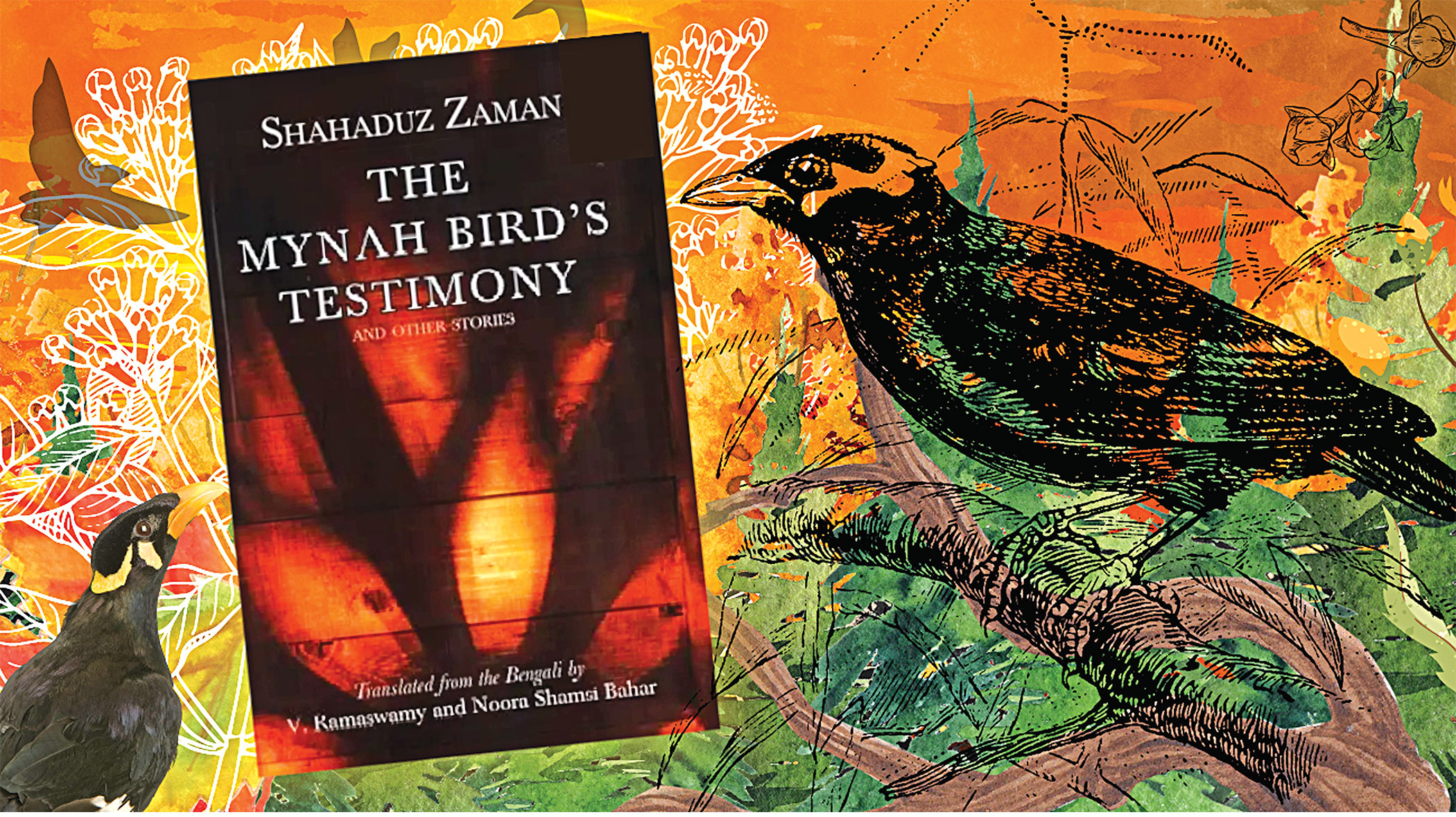

In the literary legacy, Shahaduz Zaman (1960–) stands out prominently as a significant figure in the contemporary Bengali literary landscape, utilising intertextuality throughout his works, infusing various texts and genres into his narratives. Although he works with various genres including translations, essays, novels, and docu-fictions, his main arena in literature is short stories. In his stories, the walls of the story often break down and elements of poetry, essays, and even criticism enter. And this is where different dimensions are added to Zaman's stories. One of Zaman's most intertextually rich works is "Prithibite Hoyto Brihaspatibar" (It's Maybe Thursday on Earth), the fifth story from his last storybook Mamlar Shakkhi Moyna Pakhi (Bird Myna: The Testifier [2019]).

The story is a bit about romance and a lot about corporate politics and deception. Masood, the protagonist, shares a marketing idea with his boss, Kaiser Haque, on a rain-soaked Thursday. However, the plot takes a twist when Masood stumbles upon Haque presenting the very idea as his own in an official meeting. This unexpected turn of events leaves Masood in a state of disbelief, questioning the authenticity of his boss's humanity. In a poignant analogy, Masood likens Kaiser's unfair human identity to a lemur mistakenly trapped in the identity of a shy monkey. The story concludes by shedding light on the complex contradictions inherent in human identity.

Shahaduz Zaman uses dramatic descriptions to get into the story. The narrative of the surroundings turns the time and place of the story into a stage—in the context of the vast universe, the world stands in front of the reader in the role of a playhouse. The characters are presented as actors and actresses on the stage. The storyteller describes, "Like a stage, light gradually diminishes from all sides. Clouds surround, as if preparing for the most climactic scene of a play… On the stage, all the actors and actresses gaze at the unending rain, contemplating silently." The author immerses the story's context in a theatrical ambience, intertwining genres like play and narrative within the story. This incorporation of intertextuality showcases a postmodern stylistic choice, notably exemplified by the deliberate use of 'generic indeterminacy' in the descriptive elements. By establishing parallels between the characters in the narrative and the actors and actresses on stage, the storyline contextualises Jean Baudrillard's concept of Simulacra—defined as "the generation by models of a real without origin or reality: a hyperreal." This approach brings forth the idea within a pertinent framework. In this narrative, the description replaces reality with its representation, deliberately blurring the distinctions between reality and representation. Consequently, the characters' reality becomes hyperreal within the confines of the story itself. Also, an unforgettable quote by Shakespeare may peep into the mind of the reader while reading this description—"All the world's a stage, and all the men and women merely players."

In the opening scene, as clouds gather, Masood's mobile rings. On the line, his girlfriend Ruma says, "Go stand under a shed somewhere." At that moment, a Frank Sinatra (1925–1998) song crosses Masood's mind: "Fly Me to the Moon… In other words, I love you." Contemplating Ruma's words, Masood interprets, "Go stand under a shed… In other words, I love you." The author imbues the dialogue 'go stand under a shed' with an underlying meaning, referencing Sinatra's song. This simultaneously introduces the cultural sphere of the protagonist (and the author) and exemplifies the indirect manner in which people in this region typically express their emotions. Here, the author purposefully "shapes the meaning" of his character's dialogue by intertwining it with another text—the jazz song "In Other Words."

The author derives the title of the story "Prithibite Hoyto Brihaspatibar" from the poem "Aaj Brihaspatibar" (Today is Thursday) by Binoy Majumdar (1934–2006). This can be considered as a homage to his predecessor poet. Additionally, the poem serves as a window into the protagonist, Masood's, mental state. While sharing the marketing idea, Masood recites Majumdar to Kaiser Haque:

"Today is Thursday: Maybe it's not Thursday on Earth.

Goats are grazing in the fields, the sun of the cosmos is shining on their backs.

It's time for me to sleep too.

But I can't sleep, thinking of the memory that once corn was soaked in the moonlight.

I sit and count the matchbox sticks."

Haque remains nonplussed by the poem. Masood comforts him, emphasising there's no necessity to comprehend it fully. He suggests simply envisioning a lone man seated, meticulously counting matchsticks. Masood elaborates on the scenario: The man, attempting to nap at noon, observes goats grazing in a sunlit field outside his window. The seemingly mundane occurrence of sunlight takes on cosmic significance in the man's perspective. It triggers a recollection of another cosmic event—moonlight bathing a cornfield on a serene night. Captivated by this memory, the man finds sleep elusive and resorts to passing time by counting matchsticks.

From what seems like an ordinary poem, Masood extracts the extraordinary—touching on cosmic themes, loneliness, and the serene imagery of a moonlit cornfield. It becomes evident that Masood possesses profound insights into life and the world. The poem also alludes to Masood's social position and emotional state, revealing his keen perception of the loneliness portrayed in the verses. This hints at Masood's inner sensitivity and solitude. Moreover, the man's act of counting matchsticks in the poem implicitly links to Masood's action of sharing ideas with Kaiser Haque.

At one point in the narrative, the author reveals Masood's weekend pastime of watching the American drama series Breaking Bad (2008–2013). By incorporating references to Frank Sinatra, Binoy Majumder, and such television series, the writer offers insights into the psyche of his protagonist. Simultaneously, the author engages in indirect communication with the reader by weaving references to other art media within the story. Through the narrative, the author imparts information about Masood's preferences, subtly sharing his own likes and dislikes. Shahaduz Zaman, in multiple interviews, proclaims that the purpose of his writing is not producing literature according to the readers' existing taste, rather creating readers' taste is one of his literary agenda. Therefore, by infusing intertextual elements, Zaman silently fulfils his writing agenda as well.

Deceived Masood receives another call from Ruma after seeking refuge under a shed. She checks if he is sheltered and suggests, "Don't come out until the rain stops. Instead, wait." Masood agrees to wait and, during this interlude, recalls a Mahabharata tale where Vinata had to endure a long five hundred years, awaiting the birth of her son to break free from fated slavery. The storyteller reflects, "Masood will wait. He is prepared to wait to witness who and where will hatch an egg and free him from slavery." Drawing a parallel between Masood's corporate servitude and the plight of Vinata, the mythological figure, the author intertwines Masood's uncertainty about liberation in the socio-economic context with Vinata's uncertainty about her son's birth. This juxtaposition layers the narrative with profound human emotions, enriching the story's meaning. In Umberto Eco's renowned novel, The Name of the Rose (1980), he contends, "Books always speak of other books, and every story tells a story that has already been told." In this case, the ongoing story intertwines with a mythological tale, bridging mythology and contemporary literature, encapsulating universal sentiments of simultaneous existence.

After the rain subsides, Masood returns to the flat and sits before the laptop, attempting to read the news. A gripping headline captures his attention: Someone drove a car into pedestrians on London's Westminster Bridge, resulting in several casualties. A girl jumps from the bridge into the river Thames. The attacker is killed by the police, and identified as part of a terrorist attack. The police are investigating whether the terrorist acted as a loner, a 'lone wolf.'

The news carries quite an absurd description. The description of haphazard deaths seems to paint a picture of Masood's internal bleeding. At the same time, the author leaves a mark of time in the body of the story by referring to the notorious incident of the Westminster Attack that occurred on March 22, 2017. This inclusion provides the reader with a sense of the story's timeline. The author includes that the police are investigating whether the terrorist is a loner. There is a notable parallel between Masood, who perceives the loneliness of the man in the poem "Aaj Brihaspatibar," to the loner terrorist who attacked in Westminster. If a curious reader becomes interested in the news and researches it, he/she will discover that the name of the person who attacked in Westminster is Khalid Masood. Masood, the protagonist of the story, is named after him. However, the attacker is a 52-year-old man, while the protagonist is a young man. The massacre that the old lone wolf has done in a few seconds rampage, Masood will not do that or even something like that. The storyteller has already informed that Masood would rather wait. He is ready to wait, even if he has to wait for long like Vinata, to understand the complexities of the world. By referencing a real incident from history, the author simultaneously indicates the timeline of the story and layers the narrative by contrasting and comparing the fictional character with a real one. This multi-layered approach makes the reader aware of the reality beyond the fiction and broadens their reading experience.

At one stage of news browsing, Masood's eyes are captivated by the news, "In Durgapur, Netrokona, Amirul Islam captured a shy monkey… The Forest Department's Wildlife Crime Unit was informed, alerting the Shy Monkey Research and Conservation Project." Encountering this news, Masood calls Ruma, he argues, "It's not a monkey at all. It is an animal from the Lemur group, called Primate. The poor animal's place is somewhere else. It has come here by mistake and then is thrown into the monkey's identity ignorantly, that is unfair." Ruma senses there is something wrong with Masood. He may have bumped into something. She asks. Masood replies, "What happened to this creature could also happen to humans as well. A person is inside a human, looks like a human, but he is not a human actually, maybe something else…"

Masood's conversation subtly hints at his boss. Masood is doubtful of Haque's human identity. Humans are committing deception, which is not supposed to be a human trait, with ease! At one point in the story, the storyteller states, "A strong wind blows. As if someone whispers in the wind that the skill of cheating is the Mantra (armour) of survival in this city." The fact that an abnormal action like deception is becoming normal in our lives is actually not normal. This is the parallel thing to the primate being trapped in the identity of the shy monkey, which is supposed not to be. The author infuses the story of the shy monkey in the story to wipe out this illusion of normalcy. Interestingly, the incident of the rescue of the shy monkey is indeed real. This event was reported in the Prothom Alo newspaper on March 29, 2017.

As Masood reads the news, significant events like the Westminster terrorist attack are juxtaposed with lighter news, such as the monkey rescue in Netrakona. This fluctuation between major and minor events reflects a postmodernist approach, highlighting the ups and downs of thought—what Shahaduz Zaman aptly calls "chintar nagordola." The story, through references to poems, songs, mythology, news, etc., becomes a "new tissue of past citations." The author has "absorbed" real events in the story and has thus widened the scope of the story's context and meaning.

At this juncture in the story, Ruma hangs up the phone and departs for Masood's. The storyteller describes, "Like a brightly yellow-footed starling, she will now sit on Masood's heavy chest." Zaman employs the metaphor of a starling bird with bright yellow feet to depict Ruma's approach to Masood. Upon encountering this metaphor, any acquainted reader is immediately evoked with remembrances of Jibanananda Das (1899–1954). 'Starling's yellow feet' stands as one of his signature images, recurrent in several poems.

For instance, in the poem "Jiban Othoba Mrityu" (Life or Death), Jibanananda writes, "I lie on the grass— / The starling has embraced this grass with its soft yellow feet…" In the poem "Tomra Jekhane Sadh" (Wherever You Wish), "I will see the brown-winged starling's yellow feet turn frigid in the evening, / Beneath its white feathers, in the grass in the dusk." And in the poem "He Hridoy" (O Heart):

"Yellow feet lifted, dancing, like a lean starling,

Life goes on, as if asking:

How old are you? Forty years?

Many rounds of love came and went—was there no union?"

The author operates this metaphor twice in the narrative, solidifying it as a deliberate intertextual reference. Unfortunately, borrowing others' words, metaphors, or imagery is not seen as a decent practice in the Bengali literary sphere. Utilising such references should not be misconstrued as a limitation or lack of creativity of the author. Rather, skillfully incorporating others' words showcases the writer's strength and ability to weave diverse elements into the narrative. When borrowed words, metaphors, or images are appropriately applied in different contexts, they can construct a literary bridge between two texts and enhance the multidimensionality of the reader's experience. Notably, the author inserts the word 'bright' in between Jibanananda's image of 'starling's yellow feet' (Zaman writes 'brightly yellow-footed starling'). Consequently, the metaphor sparkles like a diamond in the context of the story.

The author concludes the narrative with a poetic flourish, highlighting his distinctive writing style. Weaving bridges between diverse literary domains to construct a literary collage is a recurring hallmark of Shahaduz Zaman's storytelling. In "Prithibite Hoyto Brihaspatibar," he intertwines intertextual elements, crafting a narrative that transcends genre boundaries. The story seamlessly incorporates a harmonious blend of song, poem, mythology and real-world events, offering readers a rich and multi-dimensional literary experience.

Saiful Islam Sazid is a graduate in English literature from Southern University Bangladesh. Reach him at saifulislamszd@gmail.com.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments