I would rather stop coming here

I was too young to appreciate Fareed's exceptional qualities. It didn't impress upon me that he was a desirable bachelor and that many women would be flattered by his attention. I didn't know what love or romance was, so I didn't feel attracted to him in that sense, but I still felt possessive about him. I had a claim over him, I thought.

Here's how that feeling expressed itself: Fareed kept a photo of me on his dresser. It was a stylish one where I was wearing sunglasses and a check-patterned coat around my shoulders. It was very much a staged photo. When I saw the picture I just made a note of it, but it made no deeper impressions on me. I didn't consider the importance of this gesture by him. He noticed my apathy. It wasn't lost on him that no matter how much he tilled the fields that were my sense of romance they remained barren. "You don't behave like a mature woman," he said to me one day, a 16-year-old girl. "That's not what I am looking for. So here is my offer: either you behave like a woman, or you stop coming here. Now, what will it be?"

I thought about it for a moment. "I would rather stop coming here."

"Fine," he said, without emotion. "Don't come back."

As was the case of most of my interactions with Fareed, I felt nothing in the aftermath. Not hurt, angry or upset. I returned to my hostel unperturbed. But for some reason, I found myself back at his house a few days later not because I missed him or because I had changed my mind, but simply because that was what I wanted to do. Simply because I could.

I went in through his door. Fareed didn't see me as he was in another room doing something. I saw that my picture on the dresser had been replaced by a picture of himself. This enraged me for some reason. I took the frame and smashed it on the floor, revealing that my picture was still in the frame, just behind his. When he came into the room upon hearing the sound, I demanded to know from him why he had replaced my photo. He tried to explain but I stormed out, crying. Soon I was on the road, walking back to the hostel in tears as he followed me like a gentleman, gently coaxing me to not make a scene in public and to go back with him to the house. I only remember walking for a long time while he followed. I don't remember what came of that day in the end.

It never occurred to me that my presence in Lahore was dependent upon my scholarship, nor the corollary that I would have to do well in my studies in order to preserve my scholarship. I whiled away many hours and days singing, roaming the college campus and seeing the sites of Lahore with Fareed, who would gently encourage me to study, emphasising many times how important it was for me to complete my Bachelors degree. This was an exhortation that I found premature, given that I hadn't finished my intermediate certificate yet.

He would help me with my studies, especially with English, and thanks to him, I did better in those subjects than others, but I struggled with Home Economics subjects such as food and nutrition, clothing and textiles. Back then I had little natural intuition for cooking as my mother never asked me to cook nor to watch along as she cooked herself. One of the first tasks in my cooking test was to prepare a breakfast with eggs. I broke all the yolks and was unable to poach a single one. There was no one watching the door so I abandoned the exam without telling anyone. In the textile practical exam I had to stitch some clothes of such heavy grade that I started sweating just trying to push the needle through it. My hands became slippery with sweat and I nearly stabbed my finger with the needle. This too was a test that I snuck out of without completing. My thinking at the time was there would be no consequences to my non-appearance at these exams. Or maybe I had no thinking at all. This consequence-free existence was a fantasy that I had wholly embraced at that period of my life.

The results were released when the college residence was officially closed. I was staying with Fareed at the time. The offices were open however so when it was announced that the results were available Fareed went to the college to look for my roll number to see how I had done. When returned he looked embarrassed. He said to me "aap fail ho gaya". He seemed more embarrassed than I was. I decided it would be unwise to tell him that I failed because I left the exam without finishing. I had the belief that even if I failed my exam I would still be allowed to stay in Lahore. In a similar way, I thought that Fareed and I could continue to have a relationship even if I did not reciprocate his love, but in the end none of this would matter, as my failing grades were the harbingers of the end of my happy little life in Lahore.

Late in the summer of 1965, as I was fleeing my examination halls, war was breaking out between India and Pakistan over the perennial sore spot of Kashmir. In September, my college announced that they would close for an indefinite period of time. The students were told to find their own way home. I arrived at Fareed's house carrying my small bag and harmonium. He said that it would be inappropriate for me to stay with him, a bachelor, and asked me if I had relatives in West Pakistan who I could stay with instead. I remembered then that I had a cousin whose husband was a squadron leader in the air force in Peshawar. "Fine, I'll take you there," he said.

Fareed took a leave for seven days from work and booked two train tickets to Peshawar. It was a long journey during which I saw the vast length of the country I was in. In our cabin there were two Englishmen who were also travelling North. At one point during the journey the train stopped at a station for several hours, for what reason I no longer remember. There was no food available and all of us in the train were starving. The Englishman sat sour-faced and starving like the rest of us, eventually offering us some lozenges, as he too seemed to have no food. When the train finally moved we were able to buy food from a passing vendor at the next station, only then did the Englishman bring out his own meal, which included a whole roast chicken. Fareed whispered to me that he probably didn't reveal it earlier because he was afraid he might have to share it with us.

The other Englishman in the cabin had with him a very beautiful, expensive-looking blanket with a pink and white print. When his station arrived, he didn't want to take it with him, and offered it to anyone who wanted it. I was sorely tempted but in fear of offending Fareed I stayed silent. In the end the man left without taking his blanket. I regret not taking it to this day.

I remember little else of the journey other than passing a rock-strewn plain that Fareed said was Taxila. When we reached Peshawar we were welcomed at the station by my cousin and brother-in-law, Jashimuddin. The journey from the train station to my cousin's home was my only impression of the wider city, which to me seemed smaller, less clean and tidy compared to Lahore. But I was told you could get excellent chapli kebab here, so that was something to look forward to, as I would mostly be stuck in the house because of the war.

Fareed went to stay in a resthouse after dropping me off. He was planning to visit a friend of his who lived in the city. I stayed at my brother-in-law's place for a few days as I acclimated to my surroundings. The following day Fareed invited me to his friend's house, another bachelor. During the visit, his friend's chef brought us a try with hot water, milk, sugar and instant coffee. Fareed asked me to prepare it for them, which irritated me because I didn't like being commanded by him. However, I didn't want to embarrass him in front of his friend. So I read the instructions on the bottle and made coffee for all three of us. I found it only passable, but the other two said it was good. They may have been trying to spare my feelings.

Fareed stayed in Peshawar for a week. At that time he visited me at my relative's house. Jashimuddin's family would prepare tea and snacks for him with great enthusiasm. Fareed forged a good camaraderie with my brother-in-law, whose family seemed very impressed by Fareed overall. Perhaps they were making the assumption that I was going to marry him, which was reasonable.

On his final day, before he was about to leave for the train station, Fareed asked Jashimuddin to take care of me. I came to the living room where everyone was. Suddenly very emotional, I held Fareed from behind, put my head on his back and cried in full view of everyone. Fareed held me in his arms and his smile seemed pained. He left for the station accompanied by my brother-in-law. I didn't go up to the gate.

I disliked Jashimuddin almost instantly. As I soon discovered, he would find sneaky ways to touch me against my will. I told his wife and thankfully, she believed me. Perhaps she was clear-eyed about his character. One night I was able to get my revenge. I was in the kitchen frying fish because my cousin had asked me to help her when the power was cut because of load-shedding. While I stood in the dark kitchen, frying fish, my brother-in-law came in, calling out, "Rosy, where are you?" I knew he had the intention of putting his hands on me yet again so I turned and said, "Here I am," while holding out the spatula that had been in the extremely hot oil. Jashimuddin grabbed it thinking it was my hand and screamed. I told his wife later what happened and she laughed, saying that he had needed the lesson.

The war began fully while I was in Peshawar. Whenever we heard the huge sounds of bombers passing over us we ran out to dive into a trench we had dug near our house. One day, when one of my cousins was taking my picture a bomb fell very close to us, leaving a huge crater in the ground. We ran into the trench immediately.

My cousins, two university-aged boys who were the younger brothers of Jashimuddin's wife, were very nice to me. One of them carried a camera and it was him who took my picture when the bomb fell near the house. Another memory that remains from my time in Peshawar was that the neighbours had a dog with the same name as mine, 'Rosy', and sometimes when I heard them calling their dog I would think someone was calling me, and would answer. This made my cousins laugh.

Eventually, as the heat of war lessened, I prepared to return to Lahore. My brother-in-law sent me back on the train with a group of his air-force colleagues who were going the same way. I stayed with Fareed at his Saminabad mess for a few days while my flight was arranged for Dhaka, from where I would go to Patuakhali in Barisal where my father was posted.

I had asked Fareed to make the travel arrangements for me. However, this flight would be in the middle of a war, so there were no direct flights from Lahore to Dhaka. I would have to go to Karachi first and then take a connecting flight. Fareed asked his friend Abdul Jalil to receive me at Karachi airport, handing me a picture of his friend so that I would recognise him. Thankfully, I was able to do this without issue once I landed in Karachi. Jalil was very kind and treated me well. He took me to his house, where he offered me Ovaltine. Then he took me to the home of his relative, Colonel Kalimullah while he tried to secure the ticket to Dhaka for me. Colonel Kalimullah's wife, Tipsy, was the most beautiful woman I had ever seen, reminding me of the film star Mala Sinha. She interrogated me fiercely. She likely believed that I was Jalil's fiancee, until I convinced her otherwise. I was then put up in their daughter's room, which I would be sharing with her. She was no more than eight or nine years old.

It was a big room, and while their daughter slept I spent most of the night leafing through all the magazines that were stacked nicely in one shelf. As I went through them one by one, I tossed them to the ground, not bothering to pick them up at the end. At long last I fell asleep, waking up late in the morning. I descended to the main floor where a nice breakfast of toast, jam and boiled eggs was awaiting me. I ate hungrily, without saying 'thank you'. I requested and received extra helpings of eggs.

Jalil returned with my ticket later in the morning. I didn't ask who paid for it, nor did I offer. And actually, to this day, I don't know who did. He kindly offered to take me to the airport and I accepted. But we happened to get there too early. Jalil suggested that we visit Clifton Beach to kill time. So there we went. It was a huge beach. After walking for some time we decided to take a camel ride along. The animal proceeded at a steady but sedate rate down the beach. Unfortunately the camel driver dropped us off all the way at the other end from where we had entered, where all the taxis were. Looking at the time, we rushed to get back but no matter how fast we walked we seemed to make no progress as we were trudging sand. We finally reached the other end following an interminable slog, but it was getting late and when we hired a taxi we told the driver to rush us to the airport. We arrived to see my plane taxiing on the runway. I threw my vanity bag on the ground, sat down and started crying loudly like a child in the middle of the terminal. Meanwhile, a guilty Jalil ran about frantically trying to secure me another flight.

I eventually got on a flight and made it to Dhaka. Once there I took a steamer South. Everything had been arranged beforehand by my father so when my steamer landed in Patuakhali a group of police officers were already waiting there to meet me. From there it was another short steamer ride to where my father was, but I could hardly sit in the cabin; I kept buzzing from one side of the deck to the other. A man stood at the railing, drinking from a green coconut. I asked him if it was his intention to throw the coconut once finished and he said that it was. I asked him if I could have in that case since I wanted to eat the flesh inside. He gladly handed it to me. I didn't have a machete to open it up with. I stood around like a fool until a gentleman who had noticed my predicament stepped forward. He called a khalasi and asked him to bring a dao. Later I would come to know that he was the principal of Patuakhali College, which I would shortly join as a student.

As soon as I reached Patuakhali I put my room together, setting my trusty harmonium on the bed as I wanted to practise my rewaz. I wrote a letter to Fareed narrating my journey. I didn't mention that when I boarded the flight to Dhaka, I had made up my mind that I would be staying in East Pakistan. I had failed my exams; there was no point in returning. As was so often the case, I felt no emotion at the thought of abandoning my scholarship, leaving Fareed. I would enrol in a college in Patuakhali, I decided. It seemed a pragmatic decision and I felt carefree.

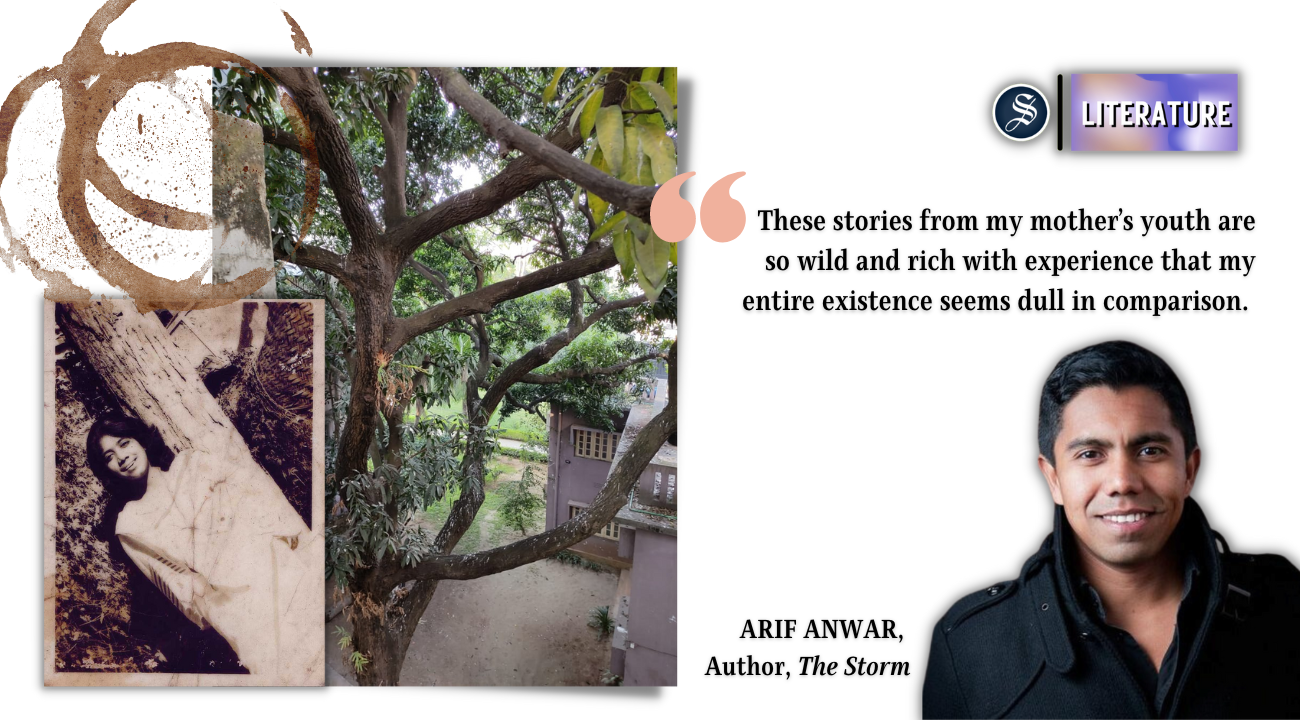

During the war months communications between the two wings of Pakistan had trickled to a stop. No goods flowed between East and West. So my family was overjoyed to see me, as my father had not heard from me in months. Later my mother would tell me that in the silence my father had assumed the worst. Unable to openly weep, he would stand at a window and stare at the empty Western sky.

I told my family that given the war I did not intend to return to Lahore. They happily agreed. I was relieved that they did not ask about my scholarship. I set about arranging for a new life in Patuakhali. Fareed kept writing to me. As always his letters were detailed and insightful, concerning the places he'd visited and the things he had seen. They also held advice, lessons. My father would read his letters first before passing them to me. Based on the letters he appeared impressed by Fareed and indicated that he approved of a match between us.

When I happened to write that in my room was a marble table-top from the zamindar house in Muktagachha, in his response Fareed made a throwaway comment that rung as snide to my ears, and based on this smallest of offences, I decided immediately that I would not pursue a relationship with him. How harsh I was with him for such minor lapses.

The thought of him marrying another woman induced no jealousy in me. I believed that he could not but be mine even if he were someone else's husband. I don't know why such a stupid idea took deep root in me, and it would take me many years to realise that he was no longer mine and never would be. He was loving to me, but he could not love me for myself. He looked at me and could only see what I could become, but not what I actually was–a rough rural girl years from maturity.

He once confided in me that at a party he had attempted to kiss a woman on the cheek while dancing but ended up kissing her ear instead. I burst out laughing when he told me the story, but again, felt no jealousy. I had a dim awareness that he may have been telling me the story with the hope of a reaction, but that was not the way it worked in my mind. I found his stories only mildly amusing, even occasionally irritating. I feigned attention, making the requisite sounds of encouragement and interest as I listened. Later I would sense his frustration that I was not yet his intellectual equal, that I was not yet one who could engage in discussions of richness and depth with him. He was careful never to express this frustration openly, channelling it rather into encouragement and exhortations to prioritise and pursue higher studies.

Later, I would think back to what he used to say: that "when wealth is gone nothing is gone" and "when health is gone something is gone" but when "character is gone everything is gone", and I would realise that he told me the story of his attempted kiss not as a boast or as an anecdote but to relay an instance of moral failure, for he was a scrupulous man to whom betrayal, lying or philandering was inconceivable.

It was in Patuakhali College that I met the man I would eventually marry, with whom I had my four children. Fareed would send frantic letters to my father to stop this marriage, whose story is not for this book, but I ignored them. My heart had inexplicably hardened against him.

Some years later, I would receive word that Fareed was in town and that he wished to see me. My husband was a high official in the government, so I took his car and went to an address in Banani. I sat in his drawing room mostly in silence, as he spoke. I remember little of the conversation other than that he was planning to buy a gift for his sister who was going to visit him in Dhaka. He didn't inquire about my married life, nor demanded to know why I hadn't married him.

My relationship with him had proceeded without encumbrance and in perfect faith. His dignity and extraordinarily humane quality forbade him from hurting my sentiments. Though I was always a disobedient junior to him, he was always ready to pardon me countless times. He did not abandon me, rather he showed great patience and the indulgence he gave me I used to do and undo anything I liked. He was never harsh with me, and now, at such a late stage in my life, I marvel at his patience. I can't find the words to express the gratitude that I never did when I knew him. The goodness in him was so pervasive that even after decades of our separation my heart breaks into pieces because of my inability to thank him. It has been many years since I have seen him, and I have accepted that I never will. I only wish him happiness. He marked the beginning of the end of my adolescence, and was also the best part of it.

Sultana Nahar is an author, lawyer, and former columnist at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments