The call of Maasai Mara

The journey begins in the dust. Fine, red ochre dust that plumes behind our safari vehicle, coating everything in a thin film that smells of ancient earth. It's the dust of the Maasai Mara, the pulse of Kenya's wildlife. The journey is a reminder that we are visitors to a land that does not officially belong to us, but is, arguably, the ancestral home of all humankind.

Travel in the wilderness dissolves barriers. We were nine strangers forged into a temporary tribe. Our Kenyan guide was our anchor, reading the land like a storybook, decoding the tales of predator and prey. The Maasai Mara is Africa's wild heart, distilled into 1,510 square kilometres of primal drama.

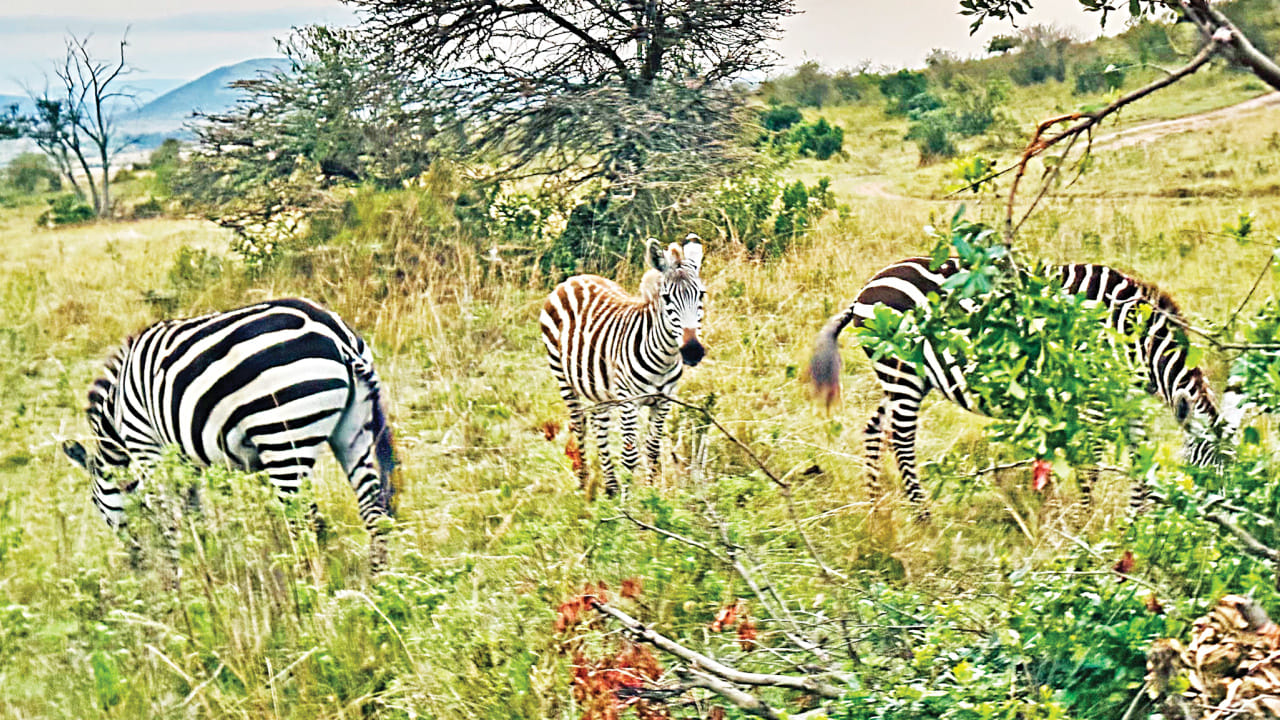

Here, a powerful duality unfolds each year. It is the stage for the Great Migration, where between July and October, over 1.5 million wildebeest, zebra, and gazelle are driven by a desperate hunt for greener pastures and water. In a parallel, modern pilgrimage, over 350,000 humans journey to the same ground, pulled by a different kind of thirst -- for wonder, for perspective, for a reconnection to nature.

Two great herds converge on the same plains: one of beasts, one of humans. The land holds its breath under the weight of both, its dusty tracks trodden by hooves desperate for survival and by tyres in pursuit of a different kind of sustenance.

We arrived in August, at the dry season's blazing climax. The African sun cast a high-contrast light transforming the grasslands into a sea of gold and throwing acacia trees into stark relief against a sky of impossible blue. Yet the true revelation wasn't the triumphant sight of lionesses on a hunt, nor even the raw, silent spectacle of a cheetah with its kill -- though those moments would come later. It was the feeling of smallness -- an unkind truth that life is a single, brief breath in a greater timeline.

The first day was a short, dazzling initiation. As the sun began its glorious descent, our guide Kelvin brought our vehicle to a halt under the ragged canopy of a lone acacia tree. The engine cut, and the world fell quiet. Into this silence came a pleasant surprise. Pranav, who had journeyed from India, produced a white box from Artcaffe, a Kenyan gourmet brand. Inside was a perfect chocolate cake, a sweet secret meant to celebrate his wife Sowmya's birthday. We stood there in the middle of the Mara and sang: "Happy Birthday."

As the sun vanished, Kelvin turned the vehicle towards our campsite, a cluster of canvas tents arranged along a concrete path. The dining area was a vortex of noise and light, a stark contrast to the silent darkness pressing in from all sides. It was alive with the clatter of cutlery and the animated chatter of other tourists. We were hungry in a way only a day in the open air can make you. We piled our plates high with rice, stewed beef, or chicken, a simple, hearty fuel that tasted like a feast.

After dinner, we retreated from the communal buzz into the silence of the African night. The path to our tent was dimly lit. The tent was surprisingly sturdy, but it was still just canvas and mesh. Inside, the final ritual was a careful scan with a flashlight for any intruder before the metallic zip of the tent sealed us in. That first night, the thin canvas felt like a flimsy curtain against the immense, breathing wilderness outside.

The next day, we woke at first light. The morning was a monochrome of grey. In the distance, a mountain ridge emerged like a phantom, silhouetted against the brightening sky. A hushed urgency filled the camp; we were getting ready for the game drive in intense anticipation. After a hurried breakfast of coffee, toast and eggs, we boarded the safari-modified Land Cruiser, Kelvin shepherding us with focused energy. As we moved away from the cluster of tents, past a line of quiet Maasai houses and towards the park gate, the sun broke over the horizon.

Our vehicle pushed deeper through the rolling landscape. And then, we saw them. Not in a dramatic charge, but in a scene of quiet power: a pride of lions, sprawled in the tawny grass. The sighting did not bring shouts, but a chorus of excited, subdued gasps and the frantic, whispered click of cameras. The hunt for wonder had begun, and it had delivered its first prize before the day had even properly started. Then, on the other side of the track, a lone lion loomed. It moved with a fluid, powerful grace; its fur glowed in the morning light. With majestic disregard for our awestruck silence, it passed by and settled into the tall grass.

The sun climbed, and the hours began to melt into the rhythm of the savanna itself. Much of the day was measured in the gentle, recurring sightings of zebras, grazing families of antelope that lifted their heads as we passed, and the hulking presence of wildebeests. And then, the cheetah. The moment of the kill was a hushed, solemn ritual. The heavy panting of the predator, the dead gazelle with exposed guts, the silent audience of safari vehicles -- everyone filming. It was a scene that felt both brutal and sacred, a necessary transaction in the economy of survival. In that silence, we confronted the raw contract of existence.

But the Mara's lessons are not only written in the hunt; they are also etched into the flow of waters.

Kelvin guided our vehicle to the bank of the Mara River, where the brown, churning water carved a path through the earth. There, two large pods of hippos were lazing like great, slick boulders, their occasional grunts and snorts echoing across the water. In expert tones, a park guide described how a crocodile, despite its fearsome jaws, is no match for the territorial fury of a two-tonne hippo, and how the mothers are ferociously protective, positioning their vulnerable cubs in the centre of the pod.

From there, we headed to a perfect spot for lunch in the shade of a lone, sprawling acacia tree, beyond the invisible line between Kenya and Tanzania. As we passed around paper boxes of grilled chicken, bread and fruits, new guests arrived: two Marabou storks. Then one more. They stood like prehistoric undertakers, their bald, pinkish heads and strong beaks giving them an air of grim authority. The next morning, we visited a nearby Maasai village. We were welcomed with a rhythmic, jumping dance, a display of vibrant energy and communal strength. Afterwards, we spoke with the villagers, and the conversation turned to tradition. One warrior, proud and straight-backed, boasted of having killed a lion, a rite of passage that once defined Maasai courage. As a reward, he explained, he had been gifted a second wife.

All journeys of convergence must, inevitably, diverge. My eleven-year-old son, Aayush, who had navigated the wilderness with wide-eyed wonder, was overcome with emotion. The prospect of parting with his own tribe of fellow travellers, his first true comrades of the road, was a weight too heavy to bear. Tears welled in his eyes. "It won't be the same," he whispered to me. "A new bond with a new group won't be possible."

After hours of sharing awe and fear and joy, the end arrived on a rain-drenched roadside. Then came a gesture that turned the moment from one of loss into one of grace. Leo Wang, a student from an American university, a member of our makeshift family, saw Aayush's heartbreak and presented him with his own set of binoculars.

Three of us left one safari vehicle for another, bound for the alkaline shores of Nakuru, about 200km away. The Kenyan landscape rolled by, green and lush after a sudden rain. Aayush, subdued, stared out his window. As the droplets streamed down the glass, he lifted a finger and traced two perfect, sad faces -- their downturned mouths and hollow eyes. I saw it from the corner of my eye and felt a lump rise in my own throat. I stared straight ahead, granting him the privacy of his sorrow. There are some griefs, even small ones, that must be felt alone to be understood.

We go to Africa for the animals. We go for the photographs, for the checklist of the Big Five, for the story to tell when we return home. But we leave having encountered something we did not expect to find: a deeper, quieter version of ourselves. This is the continent's great secret, its primal magic. It doesn't simply show us things; it pulls us inwards.

Photos: Arun Devnath

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments