What Bangladesh can learn from C. N. Yang’s legacy

Chen Ning Yang, better known as C. N. Yang, one of the greatest physicists of the 20th century and a towering figure in modern science, has passed away at the age of 103. His death marks the end of an era — but also a moment to reflect on how one visionary scientist can help reshape the destiny of a nation.

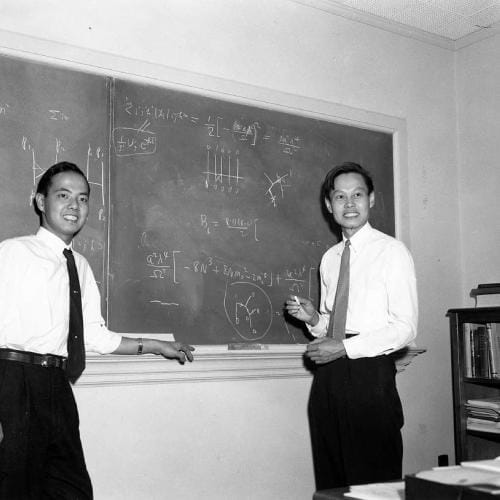

Born in 1922 in Anhui, China, Yang displayed extraordinary intellectual promise from an early age. Growing up on the serene campus of Tsinghua University, where his father was a professor of mathematics, young Yang once told his parents, "One day, I want to win the Nobel Prize." He fulfilled that dream at just 35, when he and Tsung-Dao Lee were awarded the 1957 Nobel Prize in Physics for their groundbreaking discovery of parity violation in weak interactions — a revelation that overturned one of physics' long-held symmetries and transformed our understanding of the universe.

After his early education in China, Yang pursued graduate studies at the University of Chicago under the legendary Enrico Fermi. He later became a professor at Stony Brook University, where he played a defining role in establishing one of the world's leading centres for theoretical physics. His research spanned diverse fields — from statistical mechanics and field theory to gauge symmetry — earning him the Albert Einstein Commemorative Award and honorary degrees from leading universities, including Princeton. Yet Chen Ning Yang's most enduring contribution may not lie in his equations, but in the quiet revolution he inspired in how a nation rebuilds its scientific soul.

Rekindling a nation's scientific spirit

In the 1970s and 1980s, when China was emerging from decades of political upheaval and intellectual isolation, Chen Ning Yang began returning home every summer. He did not come alone. Accompanied by teams of leading physicists from the United States and Europe, Yang embarked on a mission — not of politics, but of knowledge.

He and his colleagues organised workshops, seminars, and lectures across Chinese universities. They came not to deliver ceremonial speeches, but to teach, to mentor, and to rebuild. Laboratories were re-equipped, departments reorganised, and a new generation of Chinese physicists trained in modern theoretical and experimental methods.

Yet Chen Ning Yang's most enduring contribution may not lie in his equations, but in the quiet revolution he inspired in how a nation rebuilds its scientific soul.

Those summer visits — often underfunded and modest in scale — became the seedbeds of China's scientific renaissance. Many of the young physicists who attended those sessions went on to become leaders in their own right, heading key institutions at Tsinghua University, Peking University, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Chen Ning Yang's philosophy was simple yet transformative: a nation's scientific progress depends on openness, mentorship, and meritocracy. By fostering collaboration rather than competition, and by connecting Chinese science with the global community, he helped lay the intellectual foundations of China's modern scientific infrastructure.

A mirror for Bangladesh

As Bangladesh aspires to transform itself into a knowledge-based economy, Yang's story carries both inspiration and instruction.

Our universities brim with talent, yet the potential remains largely untapped. Research is chronically underfunded, laboratories under-equipped, and international collaboration often limited to individual efforts rather than institutional initiatives. Meanwhile, many of Bangladesh's brightest scientific minds contribute to the world's leading universities and research centres — from MIT and Oxford to Cambridge and Caltech.

What we lack is the institutional framework to bring this intellectual wealth back home, even temporarily. When Chen Ning Yang returned to China, he did so with full government support — access, autonomy, and resources. The Chinese government understood that scientific renewal was not a side project; it was a national priority. Bangladesh, too, must take that lesson seriously.

In the 1970s and 1980s, when China was emerging from decades of political upheaval and intellectual isolation, Chen Ning Yang began returning home every summer. He did not come alone. Accompanied by teams of leading physicists from the United States and Europe, Yang embarked on a mission — not of politics, but of knowledge.

Imagine a "Bangladesh Institute for Advanced Study" — a world-class centre where international and expatriate scholars spend their summers conducting workshops, mentoring young researchers, and initiating collaborative projects with local universities. With proper infrastructure — guesthouses, laboratories, libraries, and digital connectivity — such an institution could serve as a hub for academic exchange and innovation.

We once had our own visionaries who could have led such a transformation. Dr J. N. Islam, one of Bangladesh's most brilliant theoretical physicists and a Cambridge scholar, might have played a similar role had the nation built the right ecosystem around him. That opportunity was lost — but the lesson remains: talent alone cannot drive progress. It must be nurtured by an environment that values and sustains it.

The legacy of a lifelong teacher

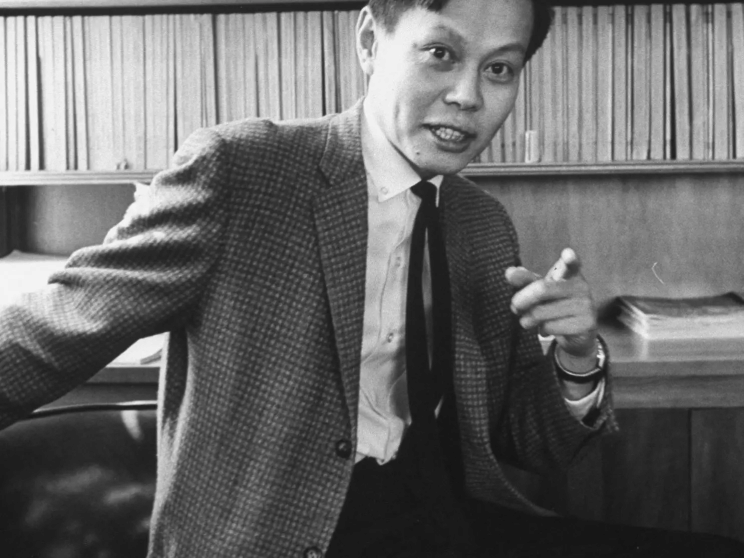

Chen Ning Yang's life was guided by a profound belief: that science transcends borders, and that knowledge must circulate freely if it is to flourish. He measured success not by the awards he won, but by the minds he inspired.

Today, as China stands as a global leader in science and technology, it owes an immense intellectual debt to this quiet, steadfast man who believed that renewal begins with education and collaboration.

Bangladesh can — and must — follow that example. With vision, institutional commitment, and a genuine respect for research, we can transform our universities into centres of creativity and discovery. Our young scientists should not have to leave home to find mentorship or opportunity; instead, the best minds of the world should find reasons to come here.

Chen Ning Yang built bridges — between East and West, between generations, between ideas and institutions. The question that remains for us is simple yet profound: will we have the courage to cross them?

Dr Kamrul Hassan Mamun is a professor in the Department of Physics at the University of Dhaka. He can be reached at khassan@du.ac.bd.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments