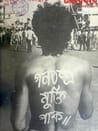

‘Let democracy be free’: The image that shook a dictator

A picture can be more powerful than a thousand words — and the photograph titled "Let Democracy Be Free" is perhaps the finest example of that truth. The image shook the foundations of the then autocratic regime. Ekushey Padak-winning photojournalist Pavel Rahman captured it on the morning of November 10, 1987 at Dhaka's Paltan. In the years that followed, the photograph became an enduring symbol of Bangladesh's struggle for democracy, etched deep in the nation's collective memory. At the time, Pavel Rahman was Chief Photographer of The New Nation newspaper, while also working as a photo correspondent for the Associated Press (AP) of America.

Pavel Rahman's career in photojournalism is as old as Bangladesh itself. Over this long span, he documented countless events that shaped the country, bringing them to the public eye. Many of his images became part of everyday conversation. Yet, few photographers in the world are remembered for a single photograph the way he is remembered for "Let Democracy Be Free." That image alone ensured his place in the hearts of the Bangladeshi people.

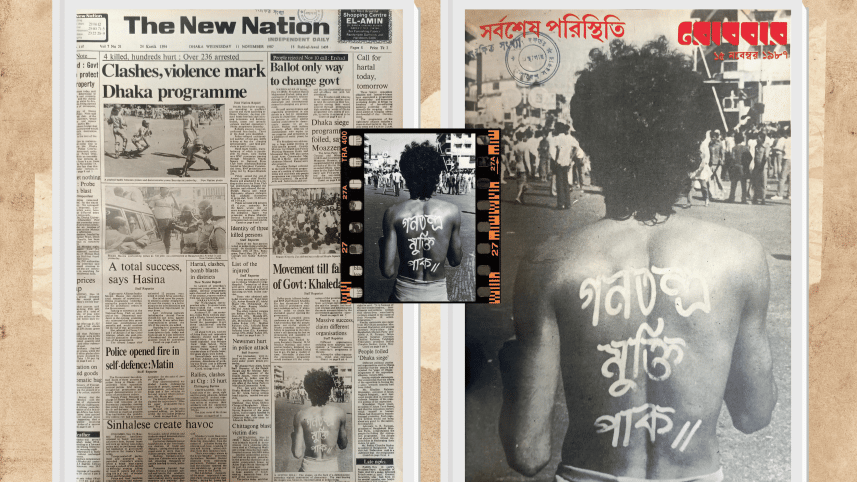

Many photographers took pictures of Nur Hossain that day. But in the face of the regime's fury, none dared to publish them. The photograph came at a high price. Initially, The New Nation's editor, Barrister Mainul Hosein, hesitated to publish it out of fear of the dictator's wrath. After persistent appeals from News Editor Amanullah Kabir and Pavel Rahman, he finally agreed — though the picture was printed with minimal prominence. The vertical image appeared on the lower right side of the fold, in two columns, without a photo credit. Once published, intelligence agencies began hunting for Pavel Rahman. To protect himself and the negative, he had to leave his home and go into hiding.

Around 10 or 10:30 a.m., a young man walked past the right side of the leftists' procession — bare-chested, dark-skinned, with dishevelled hair. On his back were the words "Let Democracy Be Free." Pavel Rahman's heartbeat quickened. He could not recall when he raised the camera, focused, or pressed the shutter. The youth lifted both arms, running his fingers through his hair, his muscles tensed. Rahman managed to take two shots — one vertical, one horizontal — before the young man vanished into the crowd.

In an interview in September 2020, Pavel Rahman recounted his real-life experiences of capturing historic events, including how he took that unforgettable photograph on November 10, 1987. Around 10 p.m. on November 9, after finishing work at The New Nation office at 1 Ramkrishna Mission Road, he set off for his home in Kalabagan. As he passed the Secretariat, he noticed that the lights were still on inside the offices. Entering the compound, he saw officials sleeping under mosquito nets, resting their heads on files placed on desks. Some were playing cards — a striking scene he quickly captured. After developing and submitting those photos, he went home late at night.

By then, police had started erecting barricades along several roads. He immediately sensed what the next day might bring. Too excited to sleep, he left home early in the morning, rode his 125cc Suzuki motorbike around the city, and finally arrived at Paltan. Something in his instincts told him, that day's defining moment would unfold there. On one shoulder hung his Nikon FM2 with an 85–200mm lens, on the other an Asahi Pentax K1000 with a 24mm lens.

By then, the seven-party alliance leader, Khaleda Zia, had staged a sit-in on a street near the House Building, surrounded by police. Fifteen-party alliance leader Sheikh Hasina had arrived in front of Paltan by jeep from the Press Club, shouted slogans, and moved towards the GPO. Pavel Rahman stood near the police box at the Paltan intersection. Soon, leftist groups carrying red flags gathered at the junction, chanting slogans and clashing briefly with riot police.

Around 10 or 10:30 a.m., a young man walked past the right side of the leftists' procession — bare-chested, dark-skinned, with dishevelled hair. On his back were the words "Let Democracy Be Free." Pavel Rahman's heartbeat quickened. He could not recall when he raised the camera, focused, or pressed the shutter. The youth lifted both arms, running his fingers through his hair, his muscles tensed. Rahman managed to take two shots — one vertical, one horizontal — before the young man vanished into the crowd.

When the procession crossed the GPO intersection and headed towards Gulistan, a gunshot rang out. Pavel Rahman took shelter near Capital Confectionery. Moments later, the renowned photojournalist Rashid Talukder came running from the direction of Begum Zia's gathering point. Seeing Pavel, he shouted, "The police have surrounded Sheikh Hasina — they might arrest her. Come quickly!" They hurried down the road in front of Ramna Bhaban towards Sheikh Hasina's location. They could not check whether anyone had been injured in the shooting; at that moment, Khaleda Zia and Sheikh Hasina were their main focus. Even a single stone thrown at either of them would make an invaluable photograph.

The Daily Ittefaq and The New Nation were under the same ownership at the time. Since The New Nation lacked a darkroom, its photojournalists regularly used Ittefaq's facilities. Around 9 p.m., three photojournalists — Rashid Talukder and Mohammad Alam from Ittefaq, and Pavel Rahman from The New Nation — were developing film in the darkroom. Reporter Khandaker Tareq knocked on the door and said, "Pavel bhai, the boy in police custody has died." Pavel rushed out and learned that the youth with the slogans against dictatorship painted across his chest and back was named Nur Hossain. Pavel told Tareq, "In five minutes, come back and say he's not dead." Tareq did so, and as a result, Talukder and Alam lost interest in the photo.

After finishing their work, Rashid Talukder and Mohammad Alam went home. Around 11:30 p.m., Pavel returned to the darkroom, developed the photographs, and hurried with the wet prints to News Editor Amanullah Kabir. Excited by what he saw, Kabir rushed with Pavel to the editor's room. But the editor refused to print the image, fearing government backlash. Pavel and Kabir, however, stood firm, arguing passionately for its publication. At last, around 1:30 a.m., the editor relented. The photograph appeared the next morning under the title A Living Bill — printed below the fold, in two columns.

Pavel later recalled, "That day I saw another photo — taken by photojournalist Mizanur Rahman — on the front page of The Daily Inqilab. It showed a boy being carried to hospital in a rickshaw, with 'Down with Dictatorship' written across his chest. Later, I heard that in front of Golap Shah's shrine, a police truck seized Nur Hossain from his companions and took him, not to the hospital, but to the police control room. There, he bled to death from morning till night. As far as I know, he wasn't shot in a place that would cause instant death. Had he been taken to hospital, his life could have been saved."

After the photo's publication, government intelligence officers began searching for Pavel Rahman. He left his home and went into hiding at his friend Fazle Bari Bachchu's house in Azimpur. On November 12, seeking advice on how to avoid arrest, he went to the Press Club — only to hear that Barrister Mainul Hosein was looking for him. At the reception, he found an address and phone number for a house on Bailey Road. When he arrived, he discovered a secret meeting of leading lawyers — Dr Kamal Hossain, Barrister Ishtiaq Ahmed, Barrister Rokanuddin Mahmud, Barrister Mainul Hosein, and others.

They all congratulated Pavel for the photograph and asked how many frames he had taken, and whether he could provide prints quickly. "Of course," he replied, "but there's one problem — the intelligence agencies are hunting for me." They each gave him their landline numbers, asking him to call immediately if he faced any trouble. The group decided that Nur Hossain's photograph would be turned into a poster and distributed nationwide. On November 15, Weekly Robbar ran the image on its cover and as its lead story — and thus the photograph spread across the entire country.

Shahadat Parvez is a photographer and researcher. The article is translated by Samia Huda.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments