How Bengal discovered Japan: A 150-year chronicle

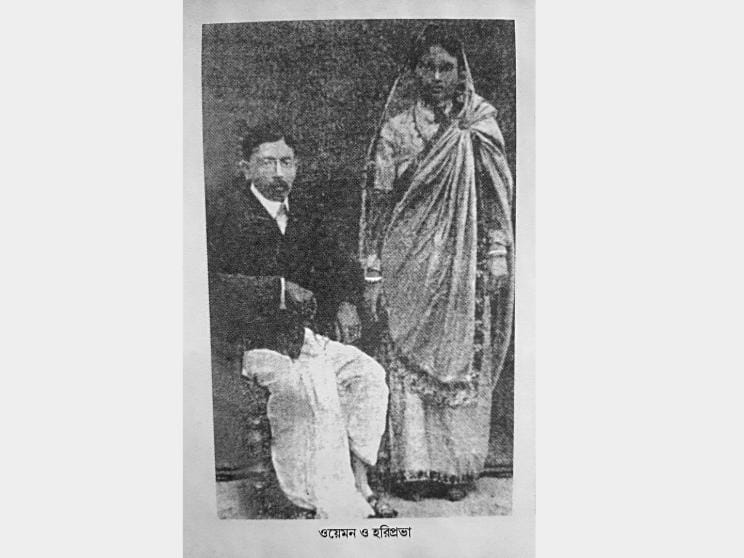

For many decades, it was believed that Rabindranath Tagore's (1861–1941) first visit to Japan in 1916 marked the initial milestone in Japan–Bengal relations. Later, in 1999, a Bengali book was reprinted in Dhaka that offered fresh insight into the century-old ties between the two nations. Bango Mohilar Japan Jatra (A Sojourn to Japan by a Bengali Woman), written by Hariprobha Mallik (1890–1972), was a reprint of her 1915 book that recounted the journey of the Dhaka-born Hariprobha, who went to Japan with her Japanese husband, Wemon Takeda, in 1912.

Some researchers opined that Bango Mohilar Japan Jatra was the first Bengali book on Japan. However, later studies revealed that, from the early decades of the 20th century, the visits of Bengalis to Japan and the publication of Bengali books about Japan were both noteworthy. At least eight books on Japan have been discovered that predate Tagore's Japan-Jatri, which was published in 1919.

In 1906, two Bengali travellers — Manmathanath Ghosh (1882–1944) of Jessore and Suresh Chandra Bandyopadhyay (1882–?) of Kolkata — journeyed to Japan and later published their accounts of the experience in Bengali in 1910. However, the fact remains that, before Ghosh's Japan-Prabash and Bandyopadhyay's Japan, another Bengali book titled Jepan had been published in Calcutta in 1858. It was a translation by Madhusudan Mukhopadhyay of the famous work Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the Chinese Seas and Japan, written by the American navigator Matthew Calbraith Perry (1794–1858).

This trend of publishing Bengali books on Japan continued vigorously even after the appearance of Japan-Jatri in 1919. Most of the works written about Japan were travelogues in nature, though there was no dearth of research books on Japan's history, literature, culture, politics, and economics either. Even before Tagore's visit to Japan, the arrival of Japanese artists and writers in Santiniketan had already inspired him with great enthusiasm for the land of the rising sun. After a few attempts, his efforts bore fruit in 1916. As Asia's first Nobel laureate, Tagore's visit to Japan created an unprecedented stir among the Japanese people. Although the poet had intended to publish a book compiling all his speeches delivered during his five visits to Japan—in 1916, 1924, and 1929—the collection was only published very recently, in 2007.

Tagore's association with the Japanese philosopher Okakura Tenshin (1862–1913) marked a milestone in Japan–Bengal literary and philosophical contact. Tenshin's The Book of Tea, published in 1906, laid the philosophical foundation of the idea of 'One Asia'. During his first visit to India in 1902, Tenshin came into contact with some of the leading intellectuals of Bengal, including Tagore and Swami Vivekananda (1863–1902). It may be noted, however, that Tenshin passed away before Tagore's first visit to Japan, and in 1924, Tagore opposed Tenshin's 'Asia is One' philosophy—perhaps because, by then, Tagore had moved beyond 'One Asia' towards a vision of 'One World'. The relationship between Tenshin and the Bengali poet Priyamvada Devi (1871–1935) developed into a literary romance during Tenshin's second visit to Calcutta in 1912.

Some researchers opined that Bango Mohilar Japan Jatra was the first Bengali book on Japan. However, later studies revealed that, from the early decades of the 20th century, the visits of Bengalis to Japan and the publication of Bengali books about Japan were both noteworthy. At least eight books on Japan have been discovered that predate Tagore's Japan-Jatri, which was published in 1919.

Tagore's first visit to Japan was accompanied by the young artist Mukul Chandra Dey (1895–1989). Dey's book Japan theke Jorasanko (From Japan to Jorasanko) is an important contribution to the subject, although it was published only in 2005. His autobiographical work Amar Kotha (In My Words, 1995) also includes his account of the Japan visit. Two other major Bengali writers who travelled to Japan and published books on the country were Buddhadeb Bose (1908–1974) and Annadashankar Roy (1909–2002). It may also be recalled that Sarojanlini Dutta (1887–1925), wife of Gurusaday Dutta (1882–1941), accompanied her husband on his visit to Japan in 1920. She wrote a book titled Banganari in Japan (A Bengali Woman in Japan), which was published in 1928.

Before Suresh Chandra Bandyopadhyay and Manmathanath Ghosh, another Bengali who is reported to have visited Japan was Swami Vivekananda. In 1893, Vivekananda stopped in Japan on his way to attend the World Parliament of Religions, to be held in Chicago. Though Swamiji did not write any book about his short stopover of only a few hours, there is evidence in Vivekananda's biographies that his stay in Japan had a profound impact on him. On May 31, 1893, Vivekananda left Bombay on the Peninsula ship to attend the first-ever global conference on religious coexistence. The ship made stops at Colombo, Penang (Malaya), Singapore, and Hong Kong before reaching Japan. He arrived at the port of Nagasaki, and from there travelled to Kobe, where he was allowed to disembark. Travelling by land to Yokohama, he visited three major cities in central Japan: the industrial city of Osaka, the ancient capital of Kyoto, and the present-day capital of Tokyo.

Vivekananda's contact with Okakura can also be recalled in this context. In August 1901, Vivekananda received an invitation to visit Japan but could not accept it due to health issues. Through his American friend Josephine MacLeod (1858–1949), who had been in contact with Vivekananda for seven years, Japanese nobles tried to bring him to Japan. On June 16, 1901, he wrote to MacLeod, "It is really desirable to establish contact between India and Japan." It was in this context that the Japanese Consul in India met Vivekananda and invited him to visit Japan, although he never received the invitation when it was formally extended. Sadly, the great Bengali soul passed away at the early age of thirty-nine after a prolonged illness.

The truth is that, a decade before Vivekananda's visit to Japan, another Bengali intellectual, Protap Chunder Mazoomdar (1840–1905), had visited the country. On his way back from the United States of America, Mazoomdar landed in Yokohama on December 12, 1883. Undoubtedly, it was a milestone for Bengalis setting foot in the eastern land. He not only delivered a lecture at a university but also wrote scholarly pieces on Japan—its history and culture.

Manmathanath Ghosh, the author of the first original book on Japan in Bengali, Japan Probash, was born in the village of Mathurapur in Jessore. In 1905, Ghosh joined the Swadeshi movement and abandoned his formal education to build his personal future. In 1906, he went to Japan to study industries. Two years later, he returned home and established a factory producing combs, buttons, and mats. Sangsad Bangali Charitabhidhan (Dictionary of Biographies), published in Kolkata, states that he worked in the factory for a salary of only 75 taka and that he even refused an offer of a thousand-taka salary from the King of Mysore. He also played an important role in establishing a match factory in the Bengal region. In 1933, Ghosh went to Japan for the second time to bring home-made crafts.

According to Ghosh's book, he studied soap, pencils, umbrellas, glass, and other items at the Government Art School and Technical Institution in Tokyo. In another Japanese city, Kobe, he learned to make buttons. For six months in Kobe, Ghosh received training in button-making from the household of an Indian-friendly Japanese gentleman. After completing this, he learned to make items using artificial ivory, which he studied in Osaka. Centuries ago, a high-quality technical institute had been established in Osaka. At that time, Indian students were studying in various colleges and institutes across Japan. Before completing his celluloid education, Ghosh became associated with an artificial leather factory. Simultaneously, he learned how to make hats and knives. He then learned to manufacture and use camphor. He also set up a small laboratory at home to study peppermint, menthol, essential oils, condensed milk, soap, and soda, among other items.

Happily, Ghosh returned home and did his utmost to apply and disseminate the knowledge he had gained. He made sincere efforts towards Bengal's progress through industrial development. Ghosh documented all this information in the three books he wrote about his days in Japan. Alongside Japan Probash, he also wrote Supta Japan and Nabyo Japan, both of which were published in 1915.

On the same ship that Ghosh took to Japan, he was accompanied by fifteen other young Bengalis. It may be mentioned that Tagore's son, Rathindranath Tagore (1888–1961), was also on the same vessel. According to Prasanta Kumar Pal (1938–2007), in the fifth volume of his much-hailed Rabi-Jiboni (Biography of Tagore), Tagore himself went to the wharf to see his son off. All of these young men travelled under the initiative of the Association for the Advancement of Scientific and Industrial Education of India (AASIEI), which had been established in 1904 with the objective of developing the technical skills of Indian youth. To achieve this goal, the institution arranged to send talented individuals abroad by providing them with financial assistance. However, the initiative could not continue beyond three or four years due to various reasons.

Before Tagore, another Bengali who went to Japan and wrote an extensive book on the country was Benoy Kumar Sarkar (1887–1949). Professor Sarkar first visited Japan in June 1915, staying there for only three months. Although he returned to Japan in 1916, his voluminous book on his first experience in the country was not published until 1923.

The year Sarkar paid his first visit to Japan, another Bengali— the well-known revolutionary Rash Behari Bose (1886–1945)—fled from India and took refuge there. Bose, whose name was associated with the assassination attempt on Lord Hardinge, the Viceroy of India, had to assume the pseudonym Priyanath Thakur and carry a reference letter from Rabindranath Tagore, posing as his relative, in order to evade British intelligence.

In addition to the above-mentioned books, a wide range of writings on Japan can be found in various periodicals published from different cities of Bengal. Many articles were written based on travel experiences in Japan, while others focused on diverse aspects of the country such as its birds, animals, education system, and industrial development. Some were translations from Japanese texts, while a few were written by Japanese visitors to India. Among the more than one hundred articles published on Japan during that era, one of the earliest was Bharatvarsha O Japan (India and Japan), published in 1874 in the periodical Bharat Sangskarak from Kolkata.

All these articles provided basic information about Japan in Bengali. Sometimes they included details such as the cost of travel, food, and lodging in Japan; at other times, they explored the education system, cultural components, and historical aspects of the country. An article titled Japanir Mukhe Japaner Kotha (Japan in the Words of a Japanese), published in 1895 in the journal Shiksha-Parikar, revealed many fascinating details. Any researcher working on Japan–Bengal relations cannot but be amazed by the abundance of material published from the Bengal region.

The present article has attempted to develop a sesquicentennial chronology between the two nations—the Japanese and the Bengalis. My study, however, assures me that there are many more links behind these books and the detailed reports published from the Bengali-speaking areas a hundred years ago. I believe that if they can be tied together in a single thread, the history of Japan–Bengal relations will undoubtedly become more illuminated.

Subrata Kumar Das, a Bangladeshi writer and researcher now living in Toronto, has edited books including Manmathanath Ghosh's Japan Probash (Dhaka, 2012), Benoy Kumar Sarkar's Nobin Asiar Janmodata Japan (Kolkata, 2024), and Sekaler Bangla Samoyikpotre Japan (Dhaka, 2012; Kolkata, 2024).

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments